Middle Eastern monarchies in Sudan’s war: What’s driving their interests?

Domestic factors within Sudan were the primary triggers for the outbreak of the civil war.

By Federico Donelli

The civil war in Sudan, which began in April 2023, involves several external actors. The conflict pits the Sudanese Armed Forces against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces in a quest for political and economic power.

More To Read

- IGAD rallies region to tackle deepening displacement crisis amid funding cuts, conflict

- Why UN’s gradual move back to Khartoum, Sudan is ‘an important step’

- Sudan military leader Burhan rejects US-led ceasefire plan, accuses Quad of favouring RSF

- UAE, US top diplomats discuss Sudan ceasefire efforts

- Trump to focus on ending Sudan civil war

- IGAD leads new push for Peace in Sudan as regional and global partners back three-step plan

The situation has created one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. Various foreign states have picked a side to support. They include Chad, Egypt, Iran, Libya, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

In particular, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are providing financial and military support to the warring parties, although they have denied it. Political scientist Federico Donelli, who has studied the influence of these Gulf monarchies in Sudan, unpacks the implications of their intervention.

How did the UAE and Saudi Arabia get involved in Sudan?

Domestic factors within Sudan were the primary triggers for the outbreak of the civil war. Framing the Sudanese conflict as a proxy war may underestimate or overlook important internal variables.

But it’s also important to highlight the indirect involvement of other states. In the Horn of Africa region, Sudan has interacted the most with Middle Eastern states over the past two decades. Among these states, two Gulf monarchies – Saudi Arabia and the UAE – stand out.

Political relations between Saudi Arabia and Sudan date back to the independence of the Sudanese state in 1956. And people-to-people links have flourished over centuries. This is largely because Sudan is geographically close to Saudi and the two Muslim holy cities of Mecca (Makkah) and Medina.

The case of the UAE is different. Since the beginning of the new millennium, the Emirates has expanded its economic and financial influence in Africa, investing in niche sectors such as port logistics. Sudan in particular came to the fore for the Emirates at the end of the 2010s when regional balances shifted before and after the Arab uprisings.

Between 2014 and 2015, Saudi Arabia and UAE's influence in Sudanese politics increased under President Omar al-Bashir. Both monarchies wanted to counter Iran’s ability to project power into the Red Sea and in Yemen. In 2015, after breaking off relations with Iran, Sudan contributed 10,000 troops to a Saudi-led military operation in Yemen to fight Houthi rebels. Both the Sudanese army and paramilitary forces took part, and personal links were forged.

In the post-Bashir era that began in 2019, Saudi and UAE influence has continued to grow, thanks to those direct links.

In general, both monarchies are status seekers. In a changing international context, Sudan is a testing ground for their ability to influence and shape future political settlements.

Seeing the post-2019 transition as an opportunity to influence Sudan’s regional standing, the two monarchies chose to support different factions within Sudan’s security apparatus. This external support exacerbated internal competition.

Riyadh, in conjunction with Egypt, maintained close ties with army leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. Abu Dhabi aligned itself with the head of the Rapid Support Forces, Mohamed Dagalo, or Hemedti.

Since 2019, the relationship between the UAE and Saudi Arabia has changed. After more than a decade of strategic convergence, especially on regional issues, the two Gulf monarchies began to diverge on issues like their view on political Islam. This divergence has been evident in various crisis scenarios, including in Sudan.

Although both countries jointly supported the initial Sudanese transition after Bashir’s ouster, the deterioration of relations between Hemedti and al-Burhan created conditions for a showdown between the two monarchies.

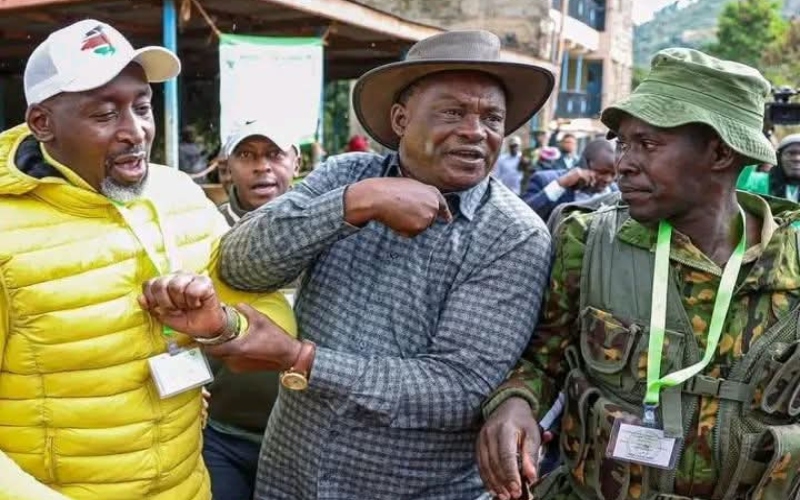

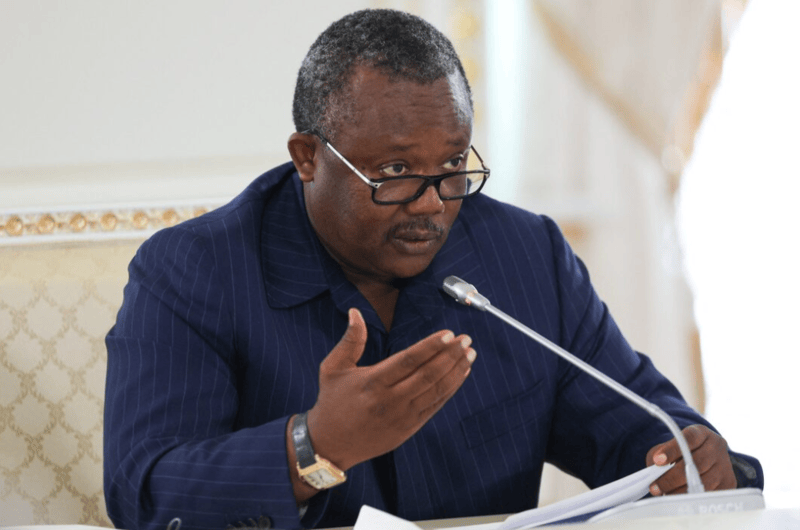

The chief of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo speaks to the Sudanese army commander, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in a past event. (Photo: AFP)

The chief of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo speaks to the Sudanese army commander, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in a past event. (Photo: AFP)The chief of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo speaks to the Sudanese army commander, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in a past event. (Photo: AFP)

However, the conflict in Sudan didn’t break out because of the rift between the UAE and Saudi Arabia. But Sudan’s local actors felt able to go to war because they were aware of external support. Once the conflict broke out, both monarchies were reluctant to withdraw local support lest they appear weak in the eyes of their regional counterpart.

Why is Sudan important to these countries?

My recent study with political scientist Abigail Kabandula shows that the UAE and Saudi Arabia gradually increased their presence in Sudan after the 2011 Arab uprisings. The fall of some regimes, including Egypt, made the two Gulf monarchies fear that instability could entangle them.

- Our analysis identifies two main reasons for the two countries’ influence in Sudan:

- changes to the regional power structure

- the strategic importance of the Horn of Africa.

The US pivoted to Asia – shifting resources from the Middle East to the Pacific – and the Arab Spring protests increased uncertainty among Gulf states. This led to a realignment of regional power dynamics and the formation of rival blocs. As a result, the UAE and Saudi Arabia sought closer ties with African countries. In Sudan, the relationship has developed through both military and political engagement.

Our analysis shows an increase in both countries’ interest in Sudan between 2012 and 2020. However, our research also highlighted some key differences in their growing influence.

In the early years after the Arab uprisings, the UAE’s influence grew rapidly, driven by concerns about the spread of protests. This was particularly important given Sudan’s proximity to Egypt.

Saudi Arabia maintained a more stable level of influence from 2010 to 2020. This was despite Riyadh also initially fearing the spread of the protests.

Both Gulf states were wary of al-Bashir’s growing ties with Turkey and Qatar, which they feared would strengthen a pro-Islamist bloc in the region. However, after Bashir’s overthrow in 2019, their approaches began to diverge.

The two Gulf monarchies view Sudan as a key country because of its geographical location.

Sudan is situated between two major regions – the Sahel and the Red Sea – characterised by instability and conflict. These regions face interconnected challenges: political instability, poverty, food insecurity, and internal and external wars. They also face population displacement, transnational crime and the threat of jihadist groups.

Moreover, Sudan is an important link between the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa. The country is a crossroads, influencing current and future geostrategic dynamics in the region.

The Gulf monarchies, including Qatar, have also invested heavily – between US$1.5 billion and US$2 billion – in Sudan’s agri-food sector, which is vital to their food security. Sudan, with its abundant water resources, offers a large amount of fertile land, making it attractive to Gulf companies.

What can we expect to see next?

Similar to other current global crises – such as those in Ukraine, the Middle East and the Democratic Republic of Congo – the conflict in Sudan seems difficult to resolve through negotiations. Two main factors contribute to this difficulty.

First, both parties see the victory of one side as entirely dependent on the defeat of the other. Such logic leaves no room for a win-win solution. Second, the current international context supports the continuation of hostilities. The global shifting balance of power provides both warring parties with opportunities for external support. This complicates efforts to find a peaceful solution.

There are now two centres of power and governance in the country. It is likely that this division will become more pronounced.

Federico Donelli is an Assistant Professor of International Relations, University of Trieste

Top Stories Today