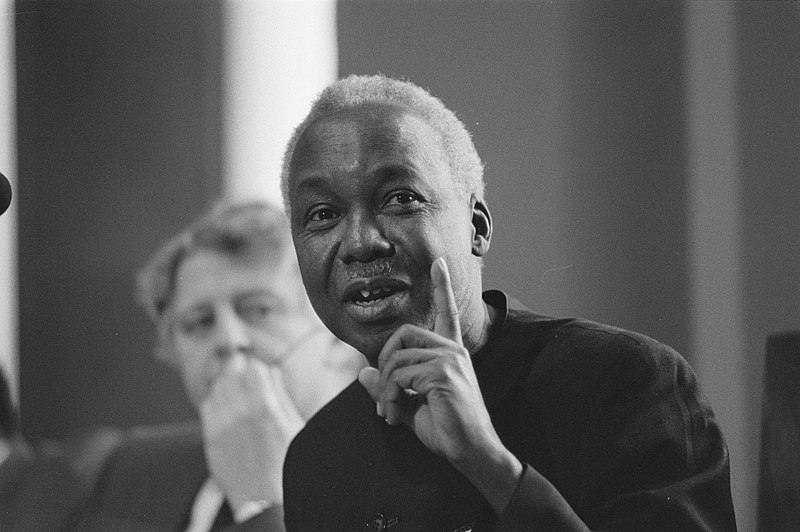

Tanzania’s independence leader Julius Nyerere built a new army fit for African liberation: How he did it

Nyerere undertook the work of unifying Tanganyika and Zanzibar in the first few months of 1964 with an eye to the region’s security.

Michelle Moyd, Michigan State University

More To Read

- Zanzibar shatters tourism record with over 700,000 visitors in just 10 months

- Zanzibar President Mwinyi secures landslide re-election with 74.8 per cent of vote

- Etihad Airways to resume direct Abu Dhabi–Zanzibar flights in June 2026

- Zanzibar opposition alleges voter fraud ahead of elections

- Zanzibar president urges peaceful campaigns, outlines development priorities

- Zanzibar announces general election schedule; early voting to begin October 28

Tanzania has long enjoyed a reputation as a peaceful country. In contrast to most of its neighbours, this East African nation of 67 million people has largely avoided large-scale violence within its borders.

That didn’t seem likely in the early years after independence from Britain in December 1961. A little over two years into independence – in January 1964 – the founding president, Julius Nyerere, faced two political crises. The first started on January 12, 1964, in the form of the Zanzibar Revolution. Weeks of violence and destruction by Afro-Shirazi Party members followed. As many as 16,000 Zanzibaris were killed or forced into exile.

Then the country’s military, the Tanganyika Rifles, mutinied. Its soldiers were incensed over inadequate pay, loss of privileges, and poor prospects for upward mobility. A rattled Nyerere needed British military support to quell the mutiny. He ordered the arrests of its leaders and effectively dismantled the entire force.

Nyerere then faced the dilemma of leading a new nation-state with no army and few resources to build one. His socialist agenda (Ujamaa, in Kiswahili) had prioritised other aspects of nation-building, especially education and public health. Nonetheless, with assistance from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and the willingness of some of its member states to provide troops, the Tanzania People’s Defence Force was established in September 1964.

In his new book, Ujamaa’s Army: The Creation and Evolution of the Tanzania People’s Defence Force, 1964-1979, Charles G. Thomas, a scholar of post-colonial African military history, skilfully narrates this complex and absorbing history. The book covers the formation and transformations of the defence force through the new nation’s first 15 years as it shed its connections to the colonial past and charted a new path.

Unlike other writing on African armies – particularly the body of work on colonial armies – this one does not centre on rank-and-file troops. Instead, Thomas’s analysis is based on rich interviews with high-ranking officers who led and moulded the force in its first two decades. This has enabled him to offer a top-down view of the construction of the army.

A rocky start

Nyerere undertook the work of unifying Tanganyika and Zanzibar in the first few months of 1964 with an eye to the region’s security. The Zanzibar revolution and the Afro-Shirazi Party’s Marxism had called attention to the island as a potential Marxist outpost. Violence against the island’s ruling party and those perceived as wealthy elites seemed to bolster this perception. In the context of the Cold War, this fuelled Western fears of Zanzibar becoming the “Cuba of East Africa”. An influx of Soviet and Chinese military advisers to Zanzibar made Western powers nervous.

Nyerere and Foreign Minister Oscar Kambona worked with Afro-Shirazi Party leader Abeid Karume to unify Tanganyika and Zanzibar to reassure Westerners.

The rollout of the defence force in September 1964 thus included members of the Zanzibari People’s Liberation Army. This signalled that the initial 1,000-man army would serve the larger interests of socialist Tanzania.

A regional role

Throughout the 1960s, Tanzania became, alongside Zambia, Botswana, Lesotho, Angola and Mozambique, a supporter of southern African liberation struggles. The OAU formally recognised this group of nations as the “frontline states” in 1975.

Nyerere convinced the OAU Liberation Committee to set up its headquarters in Dar es Salaam in 1963 because Tanganyika was already hosting many southern African exiles. Also, conflicts in neighbouring states, such as Mozambique, were spilling over into Tanganyika. It became the nerve centre for coordinating African liberation efforts.

Liberation organisations from across southern Africa also established offices in Dar es Salaam. These included the African National Congress and the Pan-Africanist Congress from South Africa; the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA); Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu) and Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu); South West Africa People’s Organisation (Swapo) from Namibia; and Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo).

The Tanzanian defence force took on a key role in the frontline liberation struggles. In 1964, it established the Special Duties Unit, which provided a logistics pipeline to serve liberation armies.

The defence force also established training camps for liberation armies within Tanzania. And it took on a protective and support function in southern Tanzania, where Frelimo’s operations against the Portuguese embroiled communities.

Tanzania’s involvement in struggles against the white settler states of southern Africa intensified in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After Portugal retreated from its colonies, Nyerere sent the defence force to help stabilise the new Frelimo government in Mozambique against the South African- and Rhodesian-backed guerrilla force Renamo.

At the same time, the book explains, Tanzania was contending with the disruptive politics and threatening military actions of its northern neighbour, Uganda.

Uganda gained independence from Britain in 1962. In 1971, Idi Amin seized power in a military coup that ousted Uganda’s first president, Milton Obote.

Amin and Nyerere antagonised each other personally, politically and militarily for the next eight years.

In 1972, Amin bombed Tanzanian border cities in retaliation for Nyerere’s support of the invasion of Uganda by Obote supporters in 1972. In 1978, Uganda annexed the Kagera Salient across its south-western border with Tanzania. In 1979, Tanzania invaded Uganda and ousted Amin from power.

The Tanzanian defence force remained in Uganda for nearly two years, providing security as the new government attempted to re-establish services and governance for post-Amin Uganda.

Catalyst for new inquiries

Thomas’s sustained research is based in large measure on hard-won connections with defence force officers. He also used alternative sources rather than relying heavily on Tanzanian, British and US archives. Canadian military archives, for example, showed how Tanzania’s forces benefited from Canadian training and resources.

OAU archival materials helped with understanding the Tanzania People’s Defence Force as part of African solidarity efforts against apartheid and colonialism.

The Conversation

Michelle Moyd, Associate Professor, Department of History, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Top Stories Today