Why the Tigray crisis is far from over

An estimated one million displaced people are grappling with high levels of food insecurity, and thousands of schools remain closed.

For over 20 years, Ethiopia was led by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition of four ethnic-based political parties representing Tigray, Amhara, Oromo, and Southern nations, nationalities and peoples. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front was the most influential party within the coalition. However, in 2018, when the Prosperity Party came into power, the front lost its important role in government.

On 4 November 2020, the federal government launched an attack on Tigray, terming it a military offensive against political aggression from the Tigrayan front. This sparked a war that lasted two years and caused severe damage to people and resources. The African Union’s lead mediator in the crisis, Olusegun Obasanjo, estimated about 600,000 civilians were killed. This makes it one of the most destructive conflicts of the 21st century.

More To Read

- Ethiopia begins registration of 7.4 million learners amid education crisis

- Nearly 50,000 people at risk, over 9,000 livestock perish as drought worsens in Tigray

- Extrajudicial killings, torture, mass detentions: US 2024 report paints grim picture on Ethiopia’s record

- Ethiopia sentences five people to death for human trafficking in landmark ruling

- Ethiopian forces implicated in 2021 killing of three aid workers in Tigray - MSF report

- Ethiopia accuses Eritrea, TPLF faction and armed groups of plotting ‘major offensive’

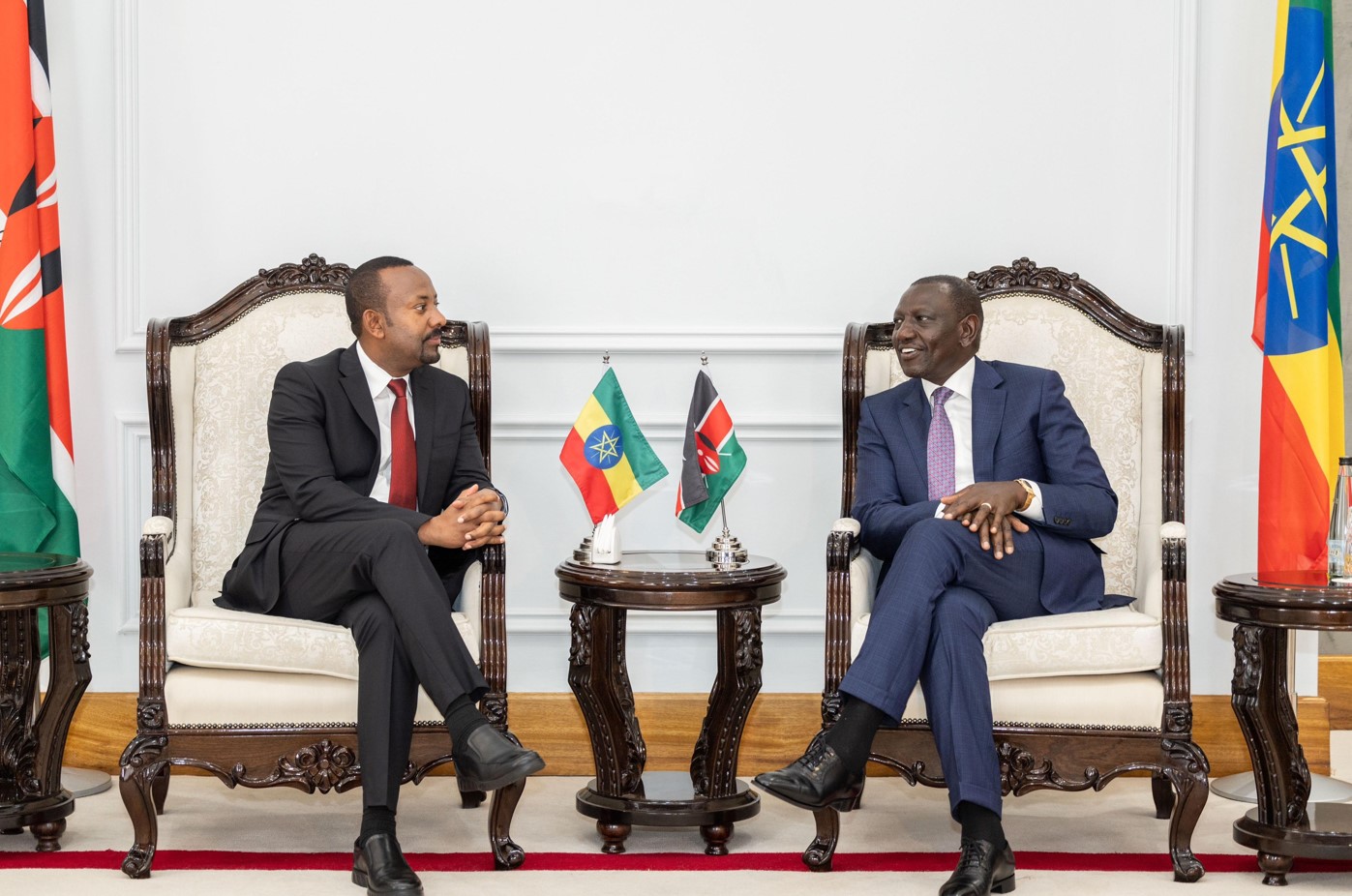

On 2 November 2022, the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front signed a peace deal in South Africa, the Pretoria agreement. More than two years later, however, Tigray still faces immense political and humanitarian challenges. Assefa Leake Gebru, who has studied post-war Tigray, explains what’s happening.

What’s the current situation in Tigray?

The 2022-2022 war and its lingering effects have thrown the Tigray region into chaos. People are grappling to get basics like food, water and medicine. The regional economy was devastated by the war. There have been no rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts so far. Humanitarian aid is limited. Imagine if your local grocery store ran out of everything and couldn’t restock – that’s the situation I have witnessed and studied in Tigray, which is affecting millions of residents.

Additionally, the leaders of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front are now fighting among themselves for power. The division is mainly between two factions: one led by former regional president Debretsion Gebremichael and the other by Getachew Reda, who heads the interim administration.

In January 2025, leaders of Tigray’s military forces supported calls from the Debretsion faction for new regional leadership. The interim administration opposed this, calling it a soft coup. The federal government considers the political faction led by Debretsion illegitimate. The military leaders’ decision also sparked public protests, with Tigrayans calling for a separation between the military and politics.

This internal division has weakened the interim administration, which was installed as part of the Pretoria agreement in March 2023.

Given this situation, the interim administration remains fragile amid serious humanitarian concerns and security threats facing the region. The interim government and dysfunctional law enforcement institutions aren’t strong enough to fix things.

Economically, jobs remain scarce. A 2024 survey found a youth unemployment rate of 81%. This situation has been created by economic collapse, asset plunder during the war and the absence of a functioning government.

Socially, people are stressed and hurting, like a community still reeling from a major fallout. It’s a pile-up of problems that are making life incredibly tough.

What, exactly, is the Pretoria agreement?

The Pretoria agreement is an important peace deal between Tigray’s political leaders and the federal government. It was signed in Pretoria, South Africa, on 2 November 2022. The African Union facilitated the peace talks hosted by South Africa.

The goal of the agreement? End the violence that began in 2020, keep people safe by calling for an immediate cessation of hostilities, allow aid like food trucks to roll in, disarm Tigray fighters and set up an interim government to restore order.

It also aimed to re-establish the Ethiopian government’s control over federal installations in Tigray.

What has been implemented and what hasn’t?

There has been some positive progress. The Pretoria agreement established the interim government. Some everyday services are back, like banks reopening and planes flying again. A few Tigray fighters have put down their weapons.

But here’s where it gets messy. Soldiers from Eritrea – which supported the Ethiopian army in the Tigray war – and militias from another Ethiopian region, Amhara, are still hanging around Tigray, raising security threats. They’re preventing internally displaced persons from going back home.

The plan to fully disarm Tigrayan fighters hasn’t been completed either. This threatens regional stability, undermines peace efforts and increases the risk of renewed violence.

What are the implications of not fully executing the Pretoria agreement?

First, the region’s humanitarian crisis could worsen. An estimated one million displaced people are grappling with high levels of food insecurity, and thousands of schools remain closed. A weak interim government and the continued occupation of parts of Tigray by armed groups have hindered the restoration of services and stifled economic progress.

Second, the division within the Tigray People’s Liberation Front makes it hard to lead the region under an interim administration. A lack of consensus on power-sharing has hindered effective governance, undermining the intended transitional authority.

Third, a weak interim government can’t keep civilians safe, which was a pillar of the Pretoria agreement. Economically, the lack of jobs and skyrocketing prices are hitting Tigrayans hard. Socially, everyone’s on edge.

Finally, there’s a risk of igniting further conflict in the region along the political fault lines between Debretsion and Getachew. There is a high chance of this situation being manipulated by Eritrean forces, who weren’t involved in the negotiations that led to the Pretoria agreement.

The fractures in the interim government provide an opportunity for neighbouring Eritrea to support one faction against the other, which could escalate into war between Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front has been one of Eritrea’s bitterest enemies. The antagonism between the two led to the 1998-2000 war between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

If these tensions keep up, Tigray will remain stuck in an awful cycle. The African Union and the international community must address these issues to prevent a spiral into further chaos.

Top Stories Today