Saudi Arabia: ‘Giga-Projects’ built on widespread labour abuses

The report is based on interviews with more than 155 former and current migrant workers and families of deceased workers across employment sectors and regions.

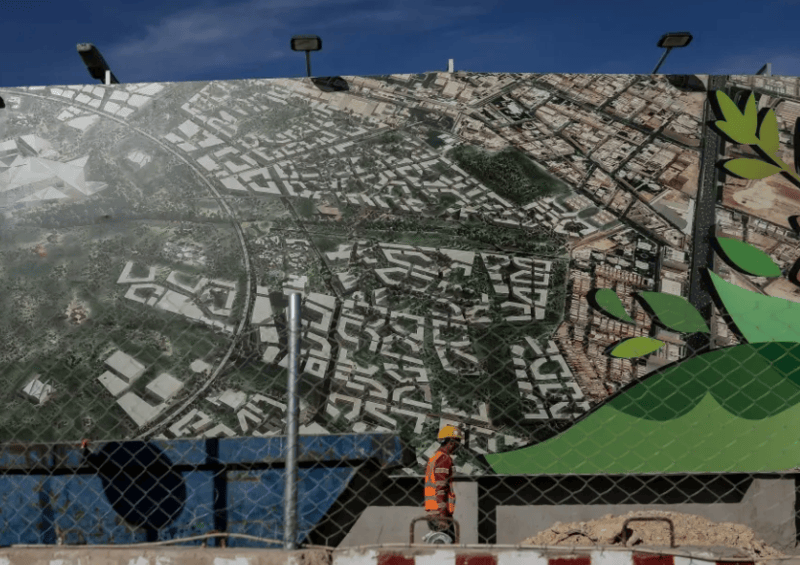

Migrant workers in Saudi Arabia are facing widespread abuses across employment sectors and geographic regions, including at high-profile giga-projects funded by or linked to Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

FIFA, the international football organisation, is set to confirm Saudi Arabia as host of the 2034 Men’s World Cup on December 11, without requiring proper human rights due diligence and binding commitments to prevent labour and other abuses.

More To Read

- Kenya’s crackdown on activists spotlighted at AU rights summit

- Tanzania slams Human Rights Watch report as “false and misleading” ahead of 2025 elections

- Somalia ratifies African Charter on Child Rights in landmark vote

- Direct Nairobi-Riyadh flights to boost Kenya’s export earnings, bilateral ties

- Kenya’s envoy Mohamed Ruwange presents credentials to Saudi Crown Prince amid recall uncertainty

- Pressure mounts on Kenya to permit visit by UN special rapporteur

The 79-page report, “‘Die First, and I’ll Pay You Later’: Saudi Arabia’s ‘Giga-Projects’ Built on Widespread Labor Abuses,” documents widespread abuses against migrant workers, some of which may amount to situations of forced labour, including exorbitant recruitment fees, rampant wage theft, inadequate protections from extreme heat, restrictions on transferring jobs, and uninvestigated worker deaths.

Saudi authorities have systematically failed to prevent or remedy these abuses, including at high-profile projects financed by its sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF).

“The human engine powering the construction of Saudi Arabia’s multibillion dollar giga-projects is the migrant workforce, who are facing widespread rights violations in Saudi Arabia without any recourse,” said Michael Page, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch.

“FIFA’s fake evaluation process to award the 2034 World Cup without legally binding human rights commitments will come at an unimaginable human cost, including adverse intergenerational impacts on migrant workers and their families.”

The report is based on interviews with more than 155 former and current migrant workers and families of deceased workers across employment sectors and regions.

Migrant workers in Saudi Arabia face widespread labour abuses at every point in the migration cycle, Human Rights Watch found.

The abuses start from the time companies recruit workers and illegally force them to pay exorbitant recruitment fees and continue with employers in Saudi Arabia violating their employment contracts by failing to honour the terms of employment and benefits stipulated in the contract.

“I was paid on time for the first two months, but never thereafter,” one migrant worker said. “When I asked my manager for payment, he would answer: ‘Die first, and I’ll pay you later.’”

Despite Saudi Arabia’s 2021 Labor Reform Initiative which claimed to make it easier for migrant workers to transfer to a different employer and leave the country freely, migrant workers continue to face barriers to mobility that abusive employers often exploit.

“I was told to take the exit permit, leave the country, and remigrate to another company,” one worker said. “They [the employer] said: ‘If we let you transfer sponsorship, we will have to let others do so as well.’”

Other employers forced workers to sign an agreement to pay their employer if they moved to a new job. Workers who did manage to change jobs also were forced to pay their former employers. One worker employed at a NEOM project—a PIF-funded giga-project that is being built in the northwest of Saudi Arabia—said he paid his previous employer more than 12,000 riyals (about US$3,200) to change jobs.

Many migrant workers also often lack the awareness and technical know-how necessary to navigate online employment contract management services. They struggle to understand their rights under the nuances of Saudi Arabia’s labour laws and cannot access support via Saudi authorities or their origin countries’ embassies.

The giga-projects often impose unrealistic, tight deadlines for projects, which translates to additional pressure on workers. Many workers are also isolated from support networks such as embassies or well-established migrant diaspora groups.

One NEOM-based worker said: “We are in the middle of nowhere. Embassies are very far away. If something goes wrong, there is nowhere we can go. There is also fear. Where do we go? Who do we tell?”

The number of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, 13.4 million, is expected to increase significantly, with planned mega- and giga-projects that will require massive new construction.

Employers also expose workers to serious dangers at job sites, including abuses linked to extreme heat for outdoor workers that are likely to increase as climate change accelerates.

A worker employed at a NEOM project said: “Every day, one or two workers faint, including during mornings and evenings. Sometimes on the way to work. Sometimes while working.” Abuses linked to extreme heat can cause lasting and potentially lethal health harm to migrant workers, including organ failure.

According to government data obtained by Human Rights Watch, 884 Bangladeshis died in Saudi Arabia between January 2024 and July 2024, of which 80 per cent of the deaths were attributed to “natural causes.” Many migrant worker deaths in Saudi Arabia are unexplained, uninvestigated, and uncompensated, leaving families of deceased migrant workers without financial support.

The wife of a deceased Indian plumber told Human Rights Watch: “He did not have any health issues. We do not believe that he died of natural death as is mentioned in the death certificate. The death was not investigated properly.”

She added: “He used to send approximately $536 [KA1] every month to cover family expenses, education, and outstanding loans. After his death, we are in a state of destitution.”

Human Rights Watch also spoke to seven former migrant workers who had previously worked in Saudi Arabia who are now dialysis patients with end-stage renal disease.

The wife of one patient told Human Rights Watch that her husband’s dialysis was covered by the Nepali government, but she was unable to afford medicine or pay for their children’s school fees in the last six months. She said: “The [Saudi] company did not provide any assistance beyond booking his [return] ticket.”

While Saudi authorities have the primary obligation to protect human rights, including labour rights, businesses also have internationally recognised responsibilities to respect human rights and avoid complicity in abuses.

The pervasive enforcement gaps in Saudi laws intended to protect migrant workers require urgent attention. However, as this report documents, while noncompliance needs to be addressed, compliance alone is also not sufficient in Saudi Arabia’s context, where many laws themselves fail by design to meet international norms and the country’s obligations under international human rights instruments, Human Rights Watch said.

Saudi Arabia’s 2034 Men’s World Cup bid submitted to FIFA failed to adequately report and address rights abuses prevalent in the country and to offer any concrete assurances that the abuses will be addressed, despite the massive construction required, including 11 new and four refurbished stadiums; more than 185,000 new hotel rooms; and significant airport, road, rail, and bus network expansion.

FIFA has engineered the World Cup hosting process to ignore the blatant human rights risks, including a forced labour complaint against Saudi Arabia filed by the global trade union Building and Wood Workers’ International (BWI) at the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 2024.

Human Rights Watch wrote to FIFA on November 4, 2024, sharing findings and documentation of widespread and serious labour rights abuses linked to mega- and giga-projects in Saudi Arabia. FIFA has not responded.

“Saudi authorities, who are spending billions to launder their abominable human rights reputation, would be better served by effectively implementing labour reforms they’ve promised but so far failed to deliver on,” Page said.

Top Stories Today