Thousands of refugee children in Egypt left out of school, HRW reports

The Egyptian government fails to fully guarantee free education since public schools charge fees for both Egyptians and non-Egyptians. Some categories of students are exempt, but not refugee or asylum-seeking students.

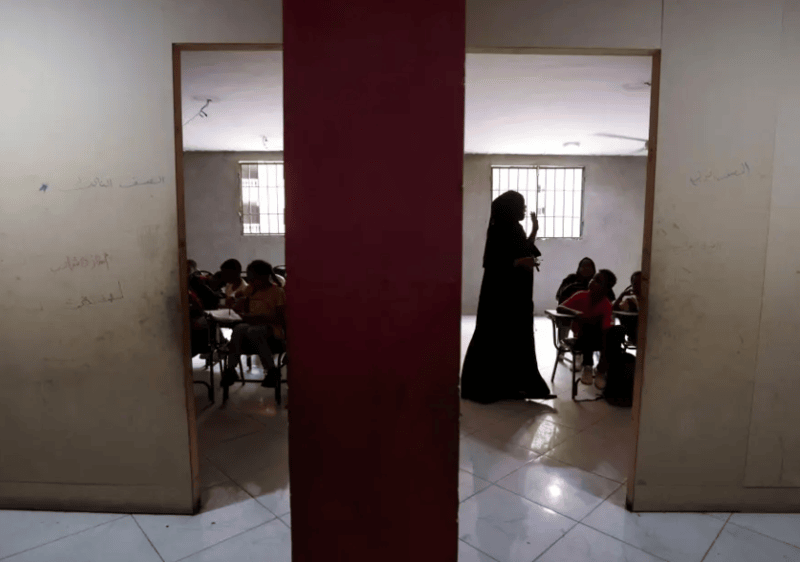

Tens of thousands of refugee and asylum-seeking children in Egypt are out of school, in many cases due to significant bureaucratic registration barriers and a lack of free, publicly available education, Human Rights Watch said today.

The authorities should immediately remove the barriers keeping refugee and asylum-seeking children out of school, and international partners should urgently support humanitarian funding for education for refugees in Egypt.

More To Read

- Uganda stops granting refugee status to nationals from Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea

- 2025 KCSE concludes smoothly as government reports sharp decline in exam cheating cases

- Egypt rejects any attempts to divide Sudan: FM

- Tension mounts as school heads, teachers’ union reject new TSC leadership structure

- 78 people arrested over exam malpractice as KCSE enters final stretch

- UNHCR warns of deepening humanitarian crisis in Darfur, Kordofan

The Egyptian government requires proof of residency as a prerequisite to enrol in public schools, an impossible hurdle for many refugee and asylum-seeking families. Amid Egypt’s deteriorating economic crisis, fees, including for school enrollment and transportation, are also a barrier.

At school, some children face bullying, abuse, and discriminatory practices from other students and teachers, further deterring enrollment or leading students to drop out.

“Many refugee and asylum-seeking children in Egypt have found the school doors firmly shut, depriving tens of thousands of their fundamental right to education,” said Bassam Khawaja, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch.

“Egyptian authorities should ensure that all children have access to free, public primary and secondary education, regardless of their legal status.”

As of November 2024, Egypt hosts 834,000 refugees and asylum seekers registered with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). This is more than double the number from a year earlier, and the real number is most likely much higher, with the Egyptian government estimating that 1.2 million people have fled Sudan to Egypt.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that there are 246,000 school-age refugee and asylum-seeking children in Egypt, approximately half of whom were out of school as of October.

A recent assessment found that nine thousand children arrive every month and approximately half of those recently arrived were out of school. These numbers do not include the estimated 100,000 Palestinian refugees who have crossed into Egypt from Gaza in the past year and who do not register with UNHCR. According to a diplomatic source in Cairo, the vast majority have not been able to secure legal residency or enrol in public schools.

Human Rights Watch conducted 27 remote interviews with refugee community leaders, teachers, parents, and other family members from Sudan, South Sudan, Yemen, Eritrea, and Palestine.

Human Rights Watch also conducted two remote interviews with representatives of humanitarian organizations and a diplomatic source in Cairo. Researchers also reviewed Egyptian laws and regulations, official statements, and publicly available information and wrote to the Egyptian Ministry of Education and Technical Education on October 8 and to UNHCR on October 24, but did not receive a response.

“All children are receiving education except mine. One of my sons drew a picture of his school in Sudan, reflecting on his memories,” said a Sudanese father unable to register his children in school.

Egypt’s 1981 education law guarantees the right to free education for “citizens.” The government should amend the law to encompass all children in the country, including refugees, Human Rights Watch said.

School enrollment for non-Egyptians is regulated by Education Ministerial Decree 284 of 2014, which allows them to enrol in private schools but generally curtails their access to public schools, except for nationals of Sudan, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan who hold residency permits. The decree does not otherwise grant access to public schools for refugees except for students who receive scholarships from UNHCR.

A November 2023 ministerial directive amending the 2014 decree permits refugees to “exceptionally” enrol in public schools. According to UNHCR, access to public education “on equal footing to Egyptians” is currently only available to nationals of Sudan, South Sudan, Yemen, and Syria. UNHCR does not provide a legal basis for the restriction to those nationalities.

The Egyptian government fails to fully guarantee free education since public schools charge fees for both Egyptians and non-Egyptians. Some categories of students are exempt, but not refugee or asylum-seeking students.

Some of those interviewed said that refugees and asylum seekers from non-Arabic speaking countries are discriminated against in enrollment, which affects access to public schools for sizable populations, including some 40,000 registered from Eritrea and 18,700 from Ethiopia.

Under international law, Egypt is bound to guarantee that all children, irrespective of legal status, have a right to education without discrimination.

Egypt is party to several international treaties enshrining the right to free and compulsory primary education and progressively free secondary education, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

As a party to the Convention Against Discrimination in Education, Egypt is under an obligation to give foreign nationals living within its territory the same access to education as is its own nationals.

Egypt has also ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which guarantees children with disabilities the right to “access an inclusive, quality and free primary education and secondary education on an equal basis with others in the communities in which they live.”

The Egyptian government should allow refugee and asylum-seeking children of all nationalities to enrol in public schools and remove bureaucratic barriers such as the residency requirement and school fees, Human Rights Watch said.

Egypt’s international partners should increase their funding for education programmes and ensure that funds are channelled for their designated purpose.

The UN has appealed for additional funding to scale up access to education for refugees in Egypt following the conflict in Sudan, however, only 55 per cent of the appeal was funded as of November.

“Egyptian authorities should stop putting up walls that keep children who have already had to flee their home countries from getting an education,” Khawaja said. “We’ve seen in other refugee crises how barriers to education do enormous harm to an entire generation of children, and Egypt’s policies now risk doing the same.”

Bureaucratic Barriers and Residency Requirements

Bureaucratic enrollment requirements imposed by the Egyptian authorities are significant barriers that keep refugee and asylum-seeking children out of school, even if they are legally permitted to enroll in public schools. According to UNHCR, even children from the nationalities permitted to attend Egyptian public schools must bring a valid residence permit and a previously recognized school certificate in order to register.

Children without a school certificate must take a placement test, and those without a residency permit must go through a convoluted, multistep process to seek an exception from the Ministry of Education and Technical Education. According to the UN, Egyptian authorities temporarily waived residency requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic for the 2020 and 2021 academic years, allowing some 45,000 refugee children to enroll.

Refugees and asylum seekers said it was very difficult to obtain legal residency in Egypt, describing a convoluted process that can take well over a year. It entails first obtaining a UNHCR registration card, waiting for an appointment with the Foreign Affairs Ministry, collecting required documents that some do not possess, and paying a fee.

Several families interviewed said that a lack of residency requirements prevented their children from getting an education. Three Sudanese parents said they tried to enrol their children in public schools, but school administrators rejected them due to a lack of residency documents. One Yemeni mother, who arrived in Egypt in 2022, said: “We can’t register in Egyptian schools. They ask for residency. I tried to register but they rejected my children.”

A Sudanese woman who arrived in Egypt with her three daughters in 2020 said that administrators at a Cairo public school informed her they would not accept UNHCR documents and requested her passport and residency permit to enroll her children. She also said that the school's principal attempted to deter their registration, saying: “Your children will not understand us.”

Bureaucratic requirements discourage families from even trying to enroll their children. Fourteen parents interviewed said they did not try to register their children in public schools because they were aware that proof of residency would be required.

Even when refugees and asylum seekers have legal residency, Human Rights Watch found that in some cases they are still not able to enrol.

A Yemeni mother who came to Egypt in 2019 said that she tried several times to register her 16-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son. However, even though she had legal residency, public school administrators informed her each time that there was no space for her children.

School fees and other costs

Human Rights Watch found that general fees for public school students and other costs, including placement tests, supplies, school uniforms, transportation, and other necessary expenses, keep refugee and asylum-seeking children out of school.

A 2022 UN report found that such costs were the greatest barrier to education for refugees in Egypt. Public schools in Egypt charge students fees of some 210-520 Egyptian pounds (about US$4-10) per year. Additionally, the Ministry of Education and Technical Education announced placement test fees of 3,000 Egyptian pounds (about $60) in September.

Refugee and asylum-seeking children unable to enrol in public education due to bureaucratic and other administrative barriers must resort to private or informal schools, which charge even higher fees.

One Sudanese mother said that after failing to enrol her children in public school, she enrolled her two youngest daughters in an informal community school. However, she could not afford to also enrol her 10-year-old daughter due to the fees charged by these schools and had to keep her home as a result.

“Education is a right of all children,” she said. “Being a refugee shouldn’t mean that children’s future remains uncertain. It doesn't mean that children become illiterate, unable to read or write. Being a refugee means you can’t afford to pay these high fees.”

UNHCR and Catholic Relief Services provide some financial support to families toward the costs of education. In 2024, UNHCR said they had provided education cash grants to 76,400 children to support their enrolment in public schools and refugee community learning centers.

However, three families who were unable to enrol their children in public schools said that the UNHCR grants were not enough to cover community school fees.

Discrimination, bullying, and harassment

Human Rights Watch found that refugee and asylum-seeking children face bullying and racial or other forms of discrimination in schools. Four parents said that the risk of bullying and racial or other discrimination discouraged them from enrolling their children in public schools.

One Eritrean teacher who arrived in Egypt in December 2020 with her 12-year-old daughter said: “It’s difficult for our children to integrate into Egyptian schools. [Refugee] students are mistreated and insulted. We heard stories of sexual harassment too. I would rather keep my daughter at home than enrol her in public school.”

A 21-year-old South Sudanese woman who came to Egypt as a child in 2011, and went to public secondary school in Egypt, described teachers discriminating against South Sudanese and Sudanese students by separating them from Egyptians. She said they were bullied and experienced verbal and physical harassment from students, who threw stones and gum at them, damaged their books, and hit her brother in the head with a stone.

“Because of the color of our skin, they consider us non-human,” she said. “When the teacher leaves the classroom, students start insulting and hitting us. The teacher never listened to us and blamed us by shouting ‘Our children are polite, you are not polite.’”

She also said Sudanese and South Sudanese students experienced sexual harassment from both teachers and peers in her school. She said her brother was sexually assaulted by a student from his school.

“An Egyptian student chased my brother and dragged him under the stairs of our building, covered his mouth with his hand, took off his pants, and did bad things. My brother came back home crying. This experience psychologically devastated him.” When they tried to file a police complaint, an officer told them to leave without documenting the case.

Human Rights Watch has previously documented how Egyptian authorities systematically fail to investigate cases of sexual abuse against refugees.

Egyptian authorities should address bullying, racism, and other forms of discrimination and stigma in schools, and ensure that refugee and asylum-seeking families are able to report any incidents to school authorities or police and other enforcement authorities without prejudice.

Mental health concerns

Many refugee and asylum-seeking children who fled conflicts in their home countries and witnessed violence and mass killings experience anxiety, psychological distress, or trauma but have no access to psychosocial support in Egypt.

Access to quality schooling in safe and supportive environments can provide children with stability and normalcy, ensuring that children resume routines, play, and spend time with peers.

Three families said that they were concerned about the mental health of their children who found themselves trapped in their houses following displacement and violence in their home countries. None of their children were able to go to alternative learning or play centres or to get psychosocial support.

A Sudanese mother said her house was raided and her husband detained during the war in Sudan before she arrived in Egypt with her five children in December 2023. “My children suffer bedwetting as a result of what they witnessed of death and violence in Sudan,” she said. “I’m not able to do anything for them. I am worried about them. They are psychologically tired. They see their neighbours going to school happily while they’re staying all day at the apartment.”

A Sudanese father unable to register his three children in a public school due to residency requirements and unaffordable community school fees said he’s worried about the mental health of his children who fled violence in their home country and are coping in isolation in their Cairo apartment.

“My children are psychologically exhausted,” he said. “Registration in any school requires money. My children need care, they are so shattered and introverted. Our situation was good in Sudan, but we lost everything after the war.”

Egyptian authorities should ensure that children can access psychosocial support, counseling, and individual support, as needed, in schools and other child and youth-responsive settings. Egypt’s development and humanitarian partners should fund psychosocial programmes in schools and out-of-school settings to ensure that refugee and asylum-seeking children can get these services without experiencing the same bureaucratic barriers.

Informal education

Some refugees and asylum seekers, including some from countries whose nationals should be able to access public schools in Egypt, rely on informal “community” schools outside the public education system.

However, such schools provide certificates not accredited by the Ministry of Education and Technical Education, charge fees, and are vulnerable to crackdowns from the authorities. Local media reported that more than 300 Sudanese community schools shut down in 2024 amid a crackdown by Egyptian authorities for operating without a license.

Ministerial decrees regulating the establishment of community schools impose a difficult process to obtain licenses, including the need to obtain approval from the relevant embassy.

Additionally, while community schools can be set up by registered nongovernmental organizations, Egypt has in recent years curtailed the work of independent organizations under draconian laws that impose security and other restrictions on their work.

Because many community schools have functioned for years in an opaque space without official licenses, teachers, students, and families are left vulnerable to interruption, unsafe conditions, and a lack of oversight over high fees.

Top Stories Today