Makhan Singh's exhibition reveals Asian role in Kenya’s freedom struggle

The exhibition’s organiser said they plan to take it to other towns like Malindi, Kisumu, Nakuru and Nyeri.

Did the Asian community play a part in the struggle for independence in Kenya? That is the question an exhibition about trade union pioneer Makhan Singh seeks to answer through a stellar display of pictures and a description of how, without the contribution of the Asians, perhaps Kenya’s freedom from colonial Britain could have been delayed.

The exhibition is being held at the Nairobi Gallery until the end of August.

More To Read

- Spirited life of Wahu Kaara: A story of determination and struggle for a better society

- Tribute to Zarina Patel by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

- Curtain falls on Kenyan author and rights activist Zarina Patel

- Dedan Kimathi Day: National hero honoured as family demands to know burial site

- Beyond the shadows: In search for Dedan Kimathi's heroic burial 67 years on

The murals and pictures of Makhan Singh during his days as a freedom fighter bring instant fresh insights into Kenya’s freedom struggles. The exhibition ultimately puts into question why the writers of Kenya’s independence struggle downplayed the contribution of the Asian community.

When The Eastleigh Voice visited Nairobi Gallery, also known as Murumbi Art Gallery, named after Kenya’s second vice president Josephat Murumbi, an ardent art collector, we found Brian Ochieng’, the exhibition caretaker guiding visitors around artefacts in the spaces around the forlorn-looking museum located along Kenyatta Avenue.

“We are having one of the best exhibitions at the gallery. Makhan Singh’s exhibition illustrates the contribution of the Asian community to Kenya’s independence struggle in a way it has never been told. This will be an enthusiasm to historians,” an elated Ochieng’ said.

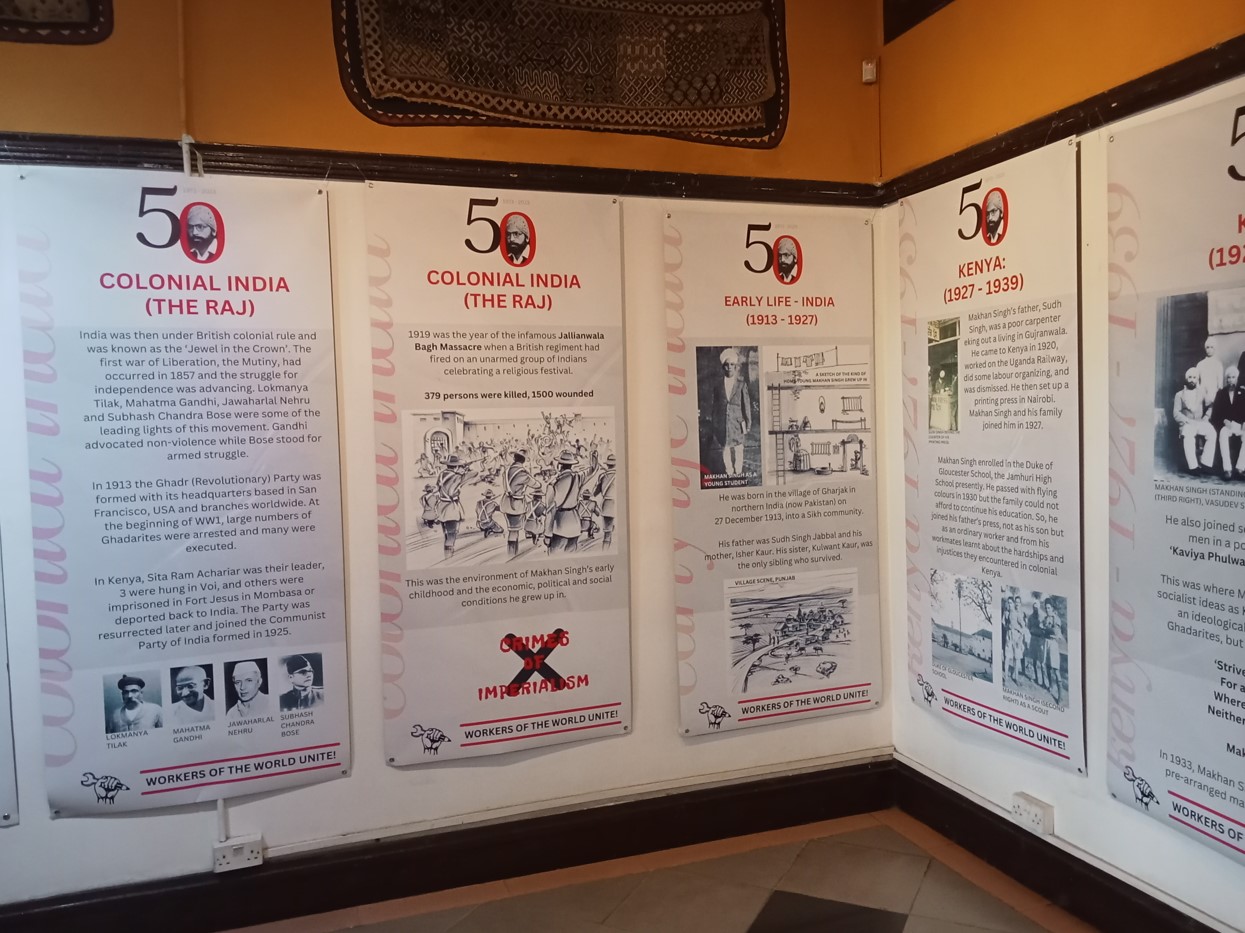

While guiding us around the well-curated exhibition room, he explained each illustration about Singh. The big imposing plaques about the uncelebrated independence hero had various themes per his massive contribution.

One titled “Life in the Shadows of Death” tells about Singh’s social life. It reads, “Though he had no scholarly qualifications, he had a wealth of experience and has left for prosperity two books – History of Kenya’s Trade Union Movement to 1952, and 1952-56 Crucial Years of Kenya’s Trade Unions which was published posthumously.”

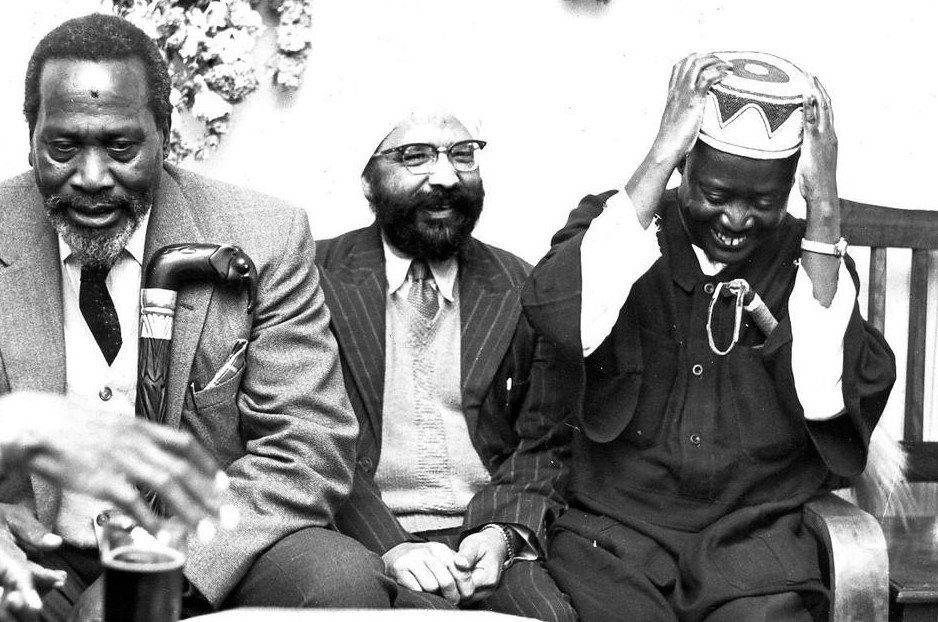

Kenya's first President Jomo Kenyatta (left) with Makhan Singh (centre) and Kenya's first Vice-President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. (Photo: Handout)

Kenya's first President Jomo Kenyatta (left) with Makhan Singh (centre) and Kenya's first Vice-President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. (Photo: Handout)

Yet on another plaque positioned next to the window titled “Tributes,” it is indicated that the Sunday Post of May 19, 1973 had Bildad Kaggia saying that, “Makhan Singh was the first non-African to train Africans in the trade union movement. Without him, there could be no trade union movements in Kenya.”

Renowned writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o in his Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary, says that Singh was a remarkable Kenyan of Asian origin, and was synonymous with the growth of modern workers’ movement and progressive trade unionism.

Other towns

Zaid Rajan, the exhibition’s organiser, said they plan to take it to other towns like Malindi, Kisumu, Nakuru and Nyeri just like they did to another independence hero of Asian origin Pio Gama Pinto.

“Our main aim is to educate Kenyans on the important role Kenya’s Asians played in the independence of our country. Their place in the history of this country has not been emphasised enough,” said Rajan.

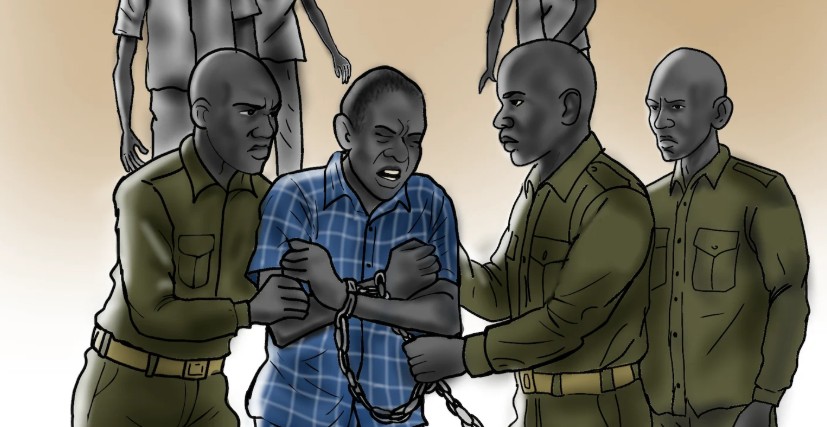

Rajan narrated how Makhan Singh and other independent heroes gave their lives to trade unionism and were even incarcerated for their struggle for a just society. Among their calls include the renaming of Park Road to honour Singh’s contribution.

Rajan is the husband of the late Zarina Patel, who was Singh’s biographer.

In her writings about the fiery trade unionist, she states that Makhan Singh was a bigger threat to the British than any other freedom fighter and hence he had to be isolated. At one time while in detention, he requested to be allowed family visits but the British instead offered to release him on condition that he would migrate from Kenya and his family would never settle anywhere in East Africa. He declined.

Singh died a disappointed man, having been side-lined by the new Kenyan leadership for being perceived variously as a leftist, a communist, and a socialist who had no place in capitalist-leaning Kenya.

In 1950, Singh did something unprecedented. In April, the Punjabi radical who had spearheaded the trade union movement in Kenya gave a call in Nairobi for “Uhuru sasa”, a Kiswahili expression meaning “freedom now”. For the first time, someone had demanded the British grant complete independence to their territories in East Africa.

A display of plaques with notes and pictures of Makhan Sing at the Nairobi Gallery. (Photo: Barack Oduor/EV)

A display of plaques with notes and pictures of Makhan Sing at the Nairobi Gallery. (Photo: Barack Oduor/EV)

Singh was soon arrested for being an “undesirable person” under the Deportation (Immigrant British Subjects) Ordinance of 1949. The arrest was not wholly unexpected. He had been orchestrating boycotts and strikes for a while, even before his call for freedom. His defence that his actions were “justified in the circumstances” was a show of defiance.

Singh spent the next 11 years in detention, being moved from one facility to another. His son Hindpal Jabbal writes that during this time, his father was not permitted any visitors, barring close family.

He was detained in various places such as Lokitaung in Turkana for three years, Maralal for seven years, and later in Dol Dol for the last year. On his release in October 1961, he found that his comrades had changed radically. He was the first non-African to join Kanu.

He was born on December 27, 1913, in the small village of Gharjak, near Gujranwala in Punjab (now in Pakistan). His father, Sudh Singh Jabbal, left for Kenya in 1920 to join the railways as an artisan, leaving Makhan and his sister under the care of their mother. He was only seven.

According to Jabbal, as a seven-year-old boy, Makhan witnessed what came to be known as the Jallian Wala Bagh incident in which hundreds of defenceless Indians were massacred in Amristrar in cold blood by a British general known as Dayer.

The incident left a lasting impression on his young mind and later formed the foundation of his selfless devotion to the freedom of Kenyans of all races as a trade unionist.

Such was his devotion that when he died in 1973, he only left Sh350 in his savings account.

“He never owed anybody any money; he never took a penny for his work in the trade union movement both in India and Kenya. Today, some of the union leaders have fleets of Mercedes Benzes at the expense of unions,’’ said his son, a former Kenya Power engineer.

Top Stories Today