The harsh reality of maternity leave, breastfeeding challenges for Kenya’s informal workers

In Kenya, exclusive breastfeeding rates for infants under six months have stalled at around 60 per cent for the past decade—below the 70 per cent global target—putting an estimated 500,000 babies at risk annually.

Barely four weeks after delivering her baby via Caesarean section, Anne Anne Njeri is already thinking about returning to work—not because she has fully healed, but because she cannot afford not to.

Her body is still in pain, and she is adjusting to life as a new mother, yet the fear of losing her job outweighs her need to rest and recover.

More To Read

- Health unions accuse insurers of sabotaging, disrupting care at Nairobi Hospital

- Nairobi Hospital suspends fee hike after insurance pushback

- Counties urged to ditch costly overseas benchmarking tours amid fiscal constraints

- Delivering in fear: The untold impact of disrespect in childbirth

- Senate faults SHA over delayed Sh8 billion payment to families of deceased civil servants

- Eight insurance firms suspend cover at Nairobi Hospital over soaring treatment costs

Njeri works in the informal private sector, where employment is based on verbal agreements rather than written contracts.

There is no paid maternity leave at her workplace. Wages are strictly tied to the days worked, and replacements are always ready to step in. As she puts it simply, “Where I work, you’re paid when you work. When you don’t, you don’t get paid.”

She has already missed four weeks of work—unpaid—and even that feels like a rare kindness.

“It’s like they’ve done me a favour by not replacing me already,” she says. “Anything more is seen as uncalled for—like I’m asking too much.”

No health insurance

Njeri also has no health insurance. The cost of her Caesarean section was covered through informal support—family contributions, loans, and community fundraising. Without employer-based health cover or access to reliable public insurance, the entire financial burden of maternity care falls on her.

Economic pressures are already making it difficult for her to exclusively breastfeed her newborn, a goal she hoped to maintain for the recommended six months.

She managed for the first four weeks, but continuing feels nearly impossible. Her job offers no accommodations for nursing mothers: no flexible hours, no clean or private space to express milk, and no option to bring her baby to work.

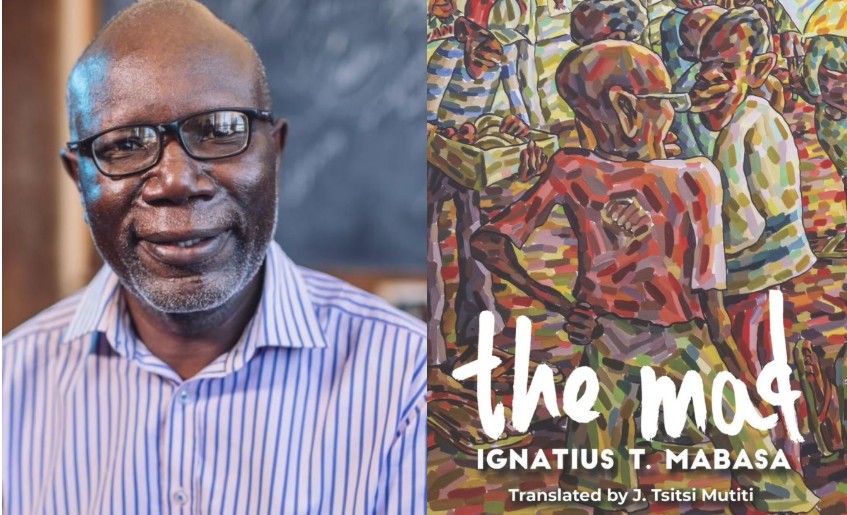

Dr Mary Kimani, a public health nutritionist with the Ministry of Health. She shared her insights on breastfeeding in Kenya. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Dr Mary Kimani, a public health nutritionist with the Ministry of Health. She shared her insights on breastfeeding in Kenya. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

“The distance between work and home is far,” she explains. “I can’t carry my baby to work, and I’m constantly worried about leaving her behind. But we have to survive. If I don’t work, we both starve.”

Maternity leave

According to Kenya’s Employment Act of 2007, all female employees are entitled to three months of fully paid maternity leave, and employers cannot terminate contracts due to pregnancy or childbirth.

Moreover, Section 71 of the Health Act, 2017, requires all employers—public and private—to provide lactation stations for breastfeeding or expressing milk during working hours.

However, these protections—along with national health insurance benefits—rarely reach women in the informal economy, which accounts for more than 80 per cent of Kenya’s workforce. For Njeri and many others, these rights exist only on paper.

Motherhood, for women like her, involves a painful trade-off: nurturing a newborn or putting food on the table.

In Kenya, exclusive breastfeeding rates for infants under six months have remained around 60 per cent over the past decade, below the global target of 70 per cent. This stagnation places an estimated 500,000 babies at risk each year.

Breastfeeding-friendly spaces

Mary Kimani, a public health nutritionist with the Ministry of Health, notes that Kenya’s labour laws support women and infant breastfeeding. She adds that the government encourages establishing breastfeeding-friendly spaces in both formal and informal workplaces, as outlined in the Labour and Health Acts.

While the formal sector has made significant progress, Kimani observes that improvements remain limited in informal work settings. Many workplaces still lack even basic lactation rooms, making it difficult for mothers to breastfeed during work hours.

Still, she emphasises that with the right education and determination, mothers—even those in challenging environments—can practice exclusive breastfeeding for the recommended six months.

“While some mothers may feel that exclusive breastfeeding is burdensome, it is also important for their own health,” Kimani explains.

“Breastfeeding helps reduce postpartum belly fat, supports uterine contraction and recovery, and helps control bleeding after childbirth.”

She adds that when mothers stop breastfeeding, milk production gradually ceases, making it important to maintain the process even when conditions are not ideal.

“In situations where there’s no suitable space to breastfeed, mothers can still express and safely discard the milk. This helps maintain milk production and ensures they can continue breastfeeding when conditions allow.”

Safe milk storage

Kimani encourages families to prioritise items that support safe breast milk storage, such as coolers, clean containers, refrigerators, and even ice cubes to keep expressed milk safe.

She notes that when pumping multiple times, the first milk expressed should be given to the baby first and not mixed with milk from later sessions, which can increase spoilage risk.

“When stored properly, breast milk can last up to 12 months in a freezer without going bad,” she explains.

Kimani also dispels a common myth - that formula is equal to breast milk.

“Formula has its place, but it lacks two critical components: immunity and the emotional bonding that comes with breastfeeding. Breast milk supports not just the baby’s nutrition, but their immune development and mother-child connection in a way formula simply cannot replicate.”

Formula milk

Formula is a safe and nutritious alternative when breastfeeding is not possible. It provides essential nutrients for growth and supports infants with special dietary needs. Formula feeding also allows shared caregiving and flexibility for parents.

Kimani notes that while some mothers feed their babies cow or goat milk, these are not ideal for infants under one year. Such milk is too high in protein, sodium, and potassium, which can strain a baby’s immature kidneys. It also lacks essential nutrients like iron, vitamin E, and essential fatty acids critical for growth and brain development.

She stresses that cow and goat milk should not be prioritised, especially when breast milk is available. Breast milk—often called “white gold”—remains the most complete and easily digestible source of infant nutrition.

While breast milk is best, formula plays a vital role in ensuring all babies receive nourishment when breastfeeding is not an option.

A 2019 qualitative study titled “Barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in urban slums of Nairobi” explored why many mothers in informal settlements struggle to practice exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), despite knowing its benefits. The study involved 33 participants—mothers, fathers, grandmothers, and health workers—from two Nairobi slums.

The findings showed that while most women understood the importance of exclusive breastfeeding, socio-economic realities made it difficult to sustain. Many had to return to informal or domestic work shortly after childbirth—often within weeks—due to poverty and lack of job protection.

Without paid maternity leave or reliable caregivers who followed feeding instructions, mothers had no choice but to introduce other foods early, shortening the recommended breastfeeding period.

Unplanned pregnancies and single motherhood added further pressure, forcing women to prioritise income over infant care.

Cultural beliefs

Cultural beliefs, often reinforced by older relatives, led some mothers to doubt breast milk sufficiency. Grandmothers or in-laws frequently encouraged early introduction of porridge or water, especially when babies cried or seemed restless.

Many mothers also worried about low milk supply, often blaming stress, exhaustion, or poor nutrition. These concerns were rarely addressed by professional support.

Although health workers promoted EBF during antenatal visits, little practical guidance was given after delivery, particularly on managing issues like poor latch, nipple pain, or persistent crying. As a result, mothers turned to traditional practices.

The study concluded that early breastfeeding cessation in slums is not due to ignorance or unwillingness but stems from structural barriers, poverty, and lack of sustained support from family and the health system.

This is especially concerning given that the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, during which infants should receive only breast milk, no other foods or liquids, not even water.

Breast milk provides all necessary nutrients, strengthens the immune system, and reduces risks of infections, stunting, and chronic diseases later in life.

Kenya’s exclusive breastfeeding rates have improved significantly over two decades—from 13 per cent in 2003 to about 60 per cent in 2022—thanks to public health campaigns and policy reforms.

However, progress has stalled since 2014, falling short of the WHO’s global target of at least 70 per cent by 2030.

Top Stories Today