DRC’s Joseph Kabila is on trial for treason: What case against the former Congolese president is all about

President Tshisekedi must tread carefully, as Kabila’s remaining loyalists, though fewer in number, could grow bolder in challenging his leadership.

Jonathan Beloff, King's College London

More To Read

- M23 rebels hands over minors taken from conflict zones in North Kivu, DRC

- UN decries ‘truly horrific’ massacres in DR Congo

- MONUSCO condemns ADF attacks that killed 89 civilians in North Kivu

- Rwanda, DR Congo talks move into ‘phase two’

- Truck that overturned in Uasin Gishu was ferrying natural rubber latex to DRC

- Over 5,000 Rwandans stream back from DR Congo after Qatar peace agreement

The Congolese military court has accused former president Joseph Kabila of treason, corruption, war crimes and supporting the March 23 Movement (M23) rebel group. During court proceedings that began in July 2025, arguments were made for utilising the death penalty against Kabila, who was in power from 2001 to 2019. The trial is going on in Kabila’s absence as the threat of arrest led him into exile.

The former president had fought against the M23’s first iteration in 2012-2013, as well as its predecessor, the National Congress for the Defence of the People, which fought the DRC government between 2006 and 2009. Jonathan R. Beloff, who has studied the regional and internal political dynamics in the DRC for over a decade, examines the implications of the case.

What is Joseph Kabila’s political history?

Joseph Kabila took over as president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) on 26 January 2001 after the assassination of his father, Laurent-Désiré. He was 29.

Before this, during the First Congo War (1996-1997), he served in the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo, which aimed to overthrow the Zairean dictator Joseph Mobutu. This war has been labelled “Africa’s World War” by historians like Gérard Prunier because of the large number of foreign actors it involved. These include Angola, Burundi, Uganda and Rwanda.

A significant number of soldiers and commanders in the alliance were Rwandan. Much of the war was conducted by Rwandan General James Kabarebe, who became a de facto father figure for Kabila, training him in military strategy, tactics and politics.

A breakdown in Rwanda’s relationship with the DRC in 1998 led to the bloody Second Congo War (1998-2003). It was between Uganda, Rwanda and to a lesser extent Burundi, who fought against the DRC and its allies like Angola and Zimbabwe. The war was mostly fought by rebels from these nations who had varying interests. During this period, Kabila became the deputy chief of staff for the Congolese military.

After he became president, he successfully applied pressure on Rwanda and Uganda to negotiate peace agreements in 2002.

Overall, his presidential term was marred by the persecution of political rivals, corruption and multiple active rebel forces in the volatile eastern region.

Further, despite the DRC’s constitution forbidding it, Kabila extended his presidency from two five-year terms, only stepping down in 2019. A political deal was struck that saw him relinquish power and hand over to Felix Tshisekedi.

What has happened to Kabila since then?

Kabila and his successor have not seen eye to eye.

Since departing from power, the former president has faced increased accusations of corruption during his presidency. Further, by 2021, many of Kabila’s supporters within the government and military had been removed.

Other Topics To Read

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- M23 rebels

- Félix Tshisekedi

- rwanda DRC conflict

- DRC

- m23

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Rwanda m23

- Paul Kagame DRC

- Joseph Kabila

- DRC-Rwanda

- War crimes DRC

- Joseph Kabila Treason

- DRC’s Joseph Kabila is on trial for treason: What case against the former Congolese president is all about

- Headlines

The relationship between the two further soured in 2023 when Kabila spoke out against Tshisekedi’s handling of the M23’s violent campaign in eastern DRC. Kabila has also criticised Tshisekedi’s use of uncontrolled militias, Wazalendo, who have been unsuccessful in combating the M23.

Kabila went into self-exile, reportedly in South Africa and other African nations, that year. He returned to eastern DRC’s regional hub Goma in May 2025, when he met with M23 leaders.

The Congolese government used Kabila’s visit to M23-controlled Goma to justify the charges brought against him. Further, the government suspended Kabila’s political party, Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie. The party represented Kabila’s interest in Congo’s legislative branch.

Soon after the party’s suspension, the Senate stripped Kabila of his immunity, allowing charges to be filed against the former president.

Why is the case against Kabila before a military court?

While Kabila doesn’t hold any political or military post – he last served as president and major-general in January 2019 – his past experience in the army led to a military rather than civilian process.

Additionally, the case is before a military court as Kabila is accused of committing treason by meeting with an opposing military force, the M23. The government seized his assets after he met and engaged with leaders of the rebel group.

While it’s not the most significant charge, Kabila also faces accusations of massive corruption during his 18-year presidency. Further, he’s being held accountable for past military decisions that led to war crimes, murder and rape during and after the Second Congo War (1998-2003).

What are the implications of the court case for DRC’s peace process?

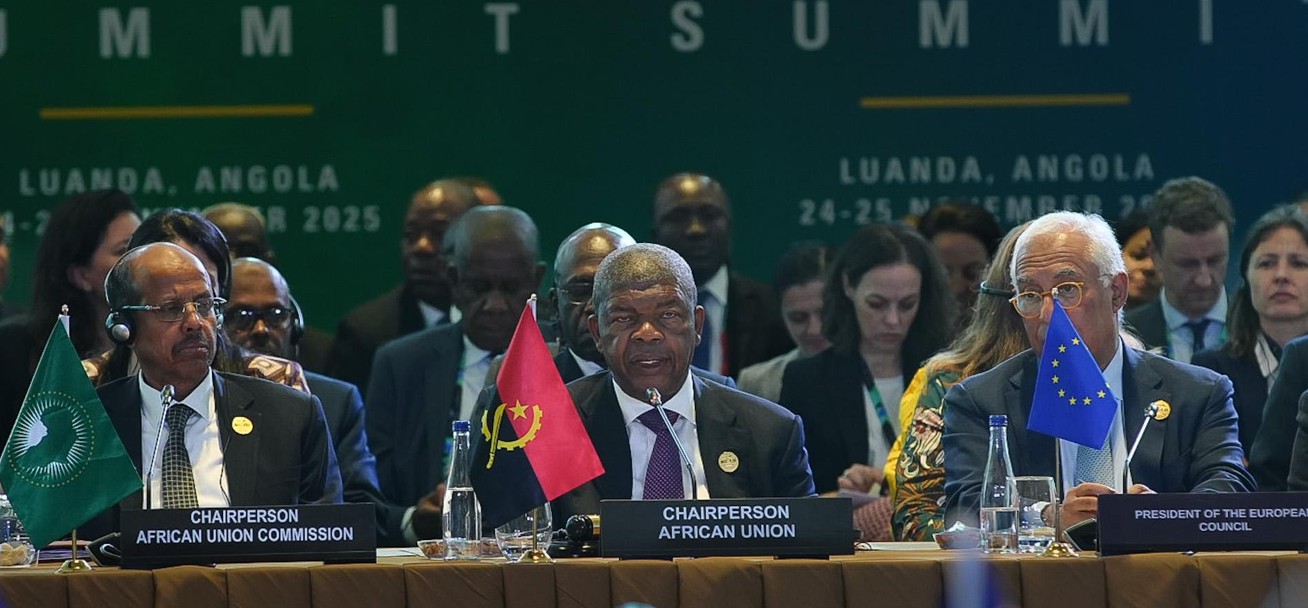

In June 2025, Rwanda and the DRC signed a peace agreement following negotiations led by Qatar and the United States.

On the surface, the agreement could lead to regional stability and growth. However, for Tshisekedi, it is a landmine of political risks.

Since the M23’s resurgence in November 2021, Tshisekedi has blamed Rwanda, as well as the Banyarwanda and Banyamulenge, who are historically Rwandan populations resident in eastern DRC, for the return of the rebel group.

The new peace deal significantly complicates Tshisekedi’s relationship with his key political allies and ministers. If they begin to believe he is caving in to Rwanda, Tshisekedi could lose the presidency ahead of next year’s election.

Thus, in my view, based on my research on Congolese instability, Tshisekedi needed to find a political distraction that his supporters could rally behind.

Kabila’s return to Goma and relationship with the M23 provided that opportunity. The court case allows Tshisekedi to highlight his fight against the rebel group and its allies. The Congolese military has been unable to significantly halt the M23’s advances.

The case also allows the president to demonstrate his tough stance on opposition figures.

The Conversation

***

Jonathan Beloff, Postdoctoral Research Associate, King's College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Top Stories Today