Eastleigh offers relief to textile traders

Traders are among the many stakeholders in the apparel industry whose prospects have been significantly influenced by the growth in textile trade in Eastleigh.

About two years ago, Dennis Otieno, a fashion designer, would travel to markets in Turkey and Sri Lanka to source raw materials for his apparel business in Athi River.

These were the places where he could get textiles at the most affordable rates, to enable him to meet his costs of operation, as well as maintain a certain profit for his other financial needs.

More To Read

- From bargains to burden, inside Gikomba’s growing pile of textile waste

- Eastleigh businesses staring at losses from uncovered risks as many shun insurance

- Untold stories of Somali culture through pictures and art

- Eastleigh sugarcane farmers savour sweet profits from the rare venture

- Business as usual in Eastleigh amid nationwide anti-Finance Bill demos

- Tarmacking of Eastleigh's Eighth Street a welcome boost for businesses

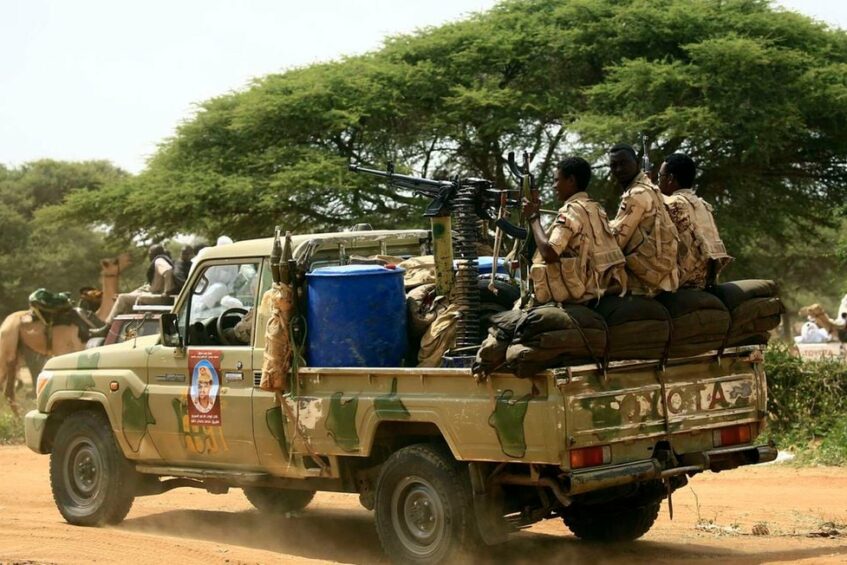

However, since conflicts began sprouting in the Middle East as well as along key shipping routes such as the Suez Canal, it has become too expensive for entrepreneurs to source raw materials from these markets.

The trader has had to look for alternative local markets such as Eastleigh, which are more favourable in terms of price, thus serving as a new growth channel for the fashion designer’s business.

“Previously, I would only source labels and packaging materials from Kenya. I had to get the fabrics, which make up nearly 80 to 90 per cent of the entire garment, from abroad,” Otieno told The Eastleigh Voice.

It would cost him $12 (Sh1,600) to get a kitenge fabric from Sri Lanka, his cheapest source abroad, which after processing he would sell for Sh3,000 to recover operating expenses.

This was too expensive considering he would sell his outfits in bulk to other traders, who would then resell them in their shops for a profit.

“My customers would often complain that the rates were too high for them to make a profit. This was an issue for me because I would also sell less,” said Otieno.

He now sources his raw material from a wholesaler at the Tansim Mall in Eastleigh, and another at the Primegate Shopping Mall, where he pays between Sh800 and Sh1,200 for a piece of kitenge, depending on quality.

Not only is it cheaper for the entrepreneur to now source raw materials locally, but it also takes him a shorter time to get the raw materials that he needs.

“I would have to wait for about three weeks for my consignment to arrive from the international markets. This went up to seven weeks when we started to witness tensions in the Middle East,” said Otieno.

From Eastleigh, the fashion designer can get fabric whenever he is in urgent need of it.

The trader is one of the many stakeholders in the apparel industry whose prospects have been significantly influenced by the growth in the textile trade in Eastleigh.

Allan Mwangi, a trader based in Utawala, would import waste materials such as cotton and silk clothes from Bangkok, Thailand to manufacture products used for decorating walls.

His company, Celomix Limited, would import these materials and bind them using an adhesive, together with minerals such as micah to create a product that, once mixed with water, could be applied to any wall surface just like normal paint.

“We used to source most of our raw materials from abroad because the quality we were looking for was not locally available, so we had to import. But shipping and declaring these items at the port would cost us money,” said Mwangi.

He now goes to the curtain sellers in Eastleigh to collect what remains after they finish measuring and cutting curtains for their clients.

This has brought down his costs of operation, enabling him to grow his business and transition from simply serving hardware operators and interior designers to serving larger entities, including real estate companies, hotels, schools, and corporations.

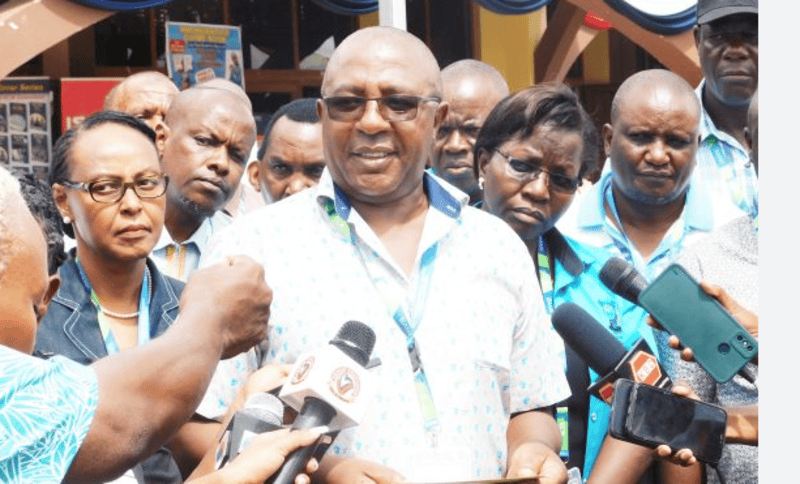

Dr. Rose Ngugi, the Executive Director at the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (Kippra), says that relying on domestic markets such as Eastleigh for the country’s textile needs could potentially create about 200,000 new jobs by 2030 and generate revenues of over $282.9 million (Sh37.2 billion) annually for the country.

However, continued reliance on goods from international traders is stifling the growth of the local textiles industry.

According to KIPPRA data, only 28,000 bales of textiles are sourced from local textile traders, with 80 per cent of them being sourced from Asian traders.

“We need to create an enabling environment for local businesses to thrive so that they can compete with their global counterparts,” Ngugi says.

This can be achieved by curtailing the operations of some foreign traders who bring cheaper but substandard goods that are affecting the competitiveness of local goods. It can also be achieved by harmonising taxes to reduce the cost of doing business.

According to data from the Eastleigh Business Traders Association, the tax on a container of goods has risen from Sh1.7 million in 2017 to more than Sh3 million currently.

This has made the country uncompetitive, with investors opting for alternative markets such as Tanzania, Rwanda, and Uganda that charge smaller levies.

In Uganda, for instance, a container of imports is charged around Sh2 million while in Tanzania, it is about Sh1 million.

Frequent harassment by authorities is also pushing Somali traders to areas such as Kisenyi in Uganda that are more relaxed and are more affordable in terms of rent.

Top Stories Today