Nuclear war threat: Why Africa’s pushing for a complete ban

As conflict and uncertainty push many Western leaders to support the madness of nuclear weapons proliferation, African leaders are in a unique position to push back against this.

Story by Olamide Samuel

At a time of heightened geopolitical tensions between Russia and Ukraine, intensified by strategic dynamics involving the US, NATO and Russia over Europe’s security, nuclear weapons are back on the agenda.

More To Read

In recent times, Russia has openly threatened to use nuclear weapons. The UK and France are considering ways to rapidly increase their nuclear weapons stockpiles.

Germany, Poland, Sweden, Finland, South Korea and Japan are now seeking nuclear weapons capabilities.

Even a limited nuclear war in Europe would lead to catastrophic global climatic effects. Huge amounts of debris thrown high into the atmosphere would block sunlight, causing global temperatures to drop sharply. It would be much harder to grow food around the world.

This would severely threaten Africa’s food security, exacerbating mass migration, disrupting supply chains and potentially collapsing public order systems.

How should African countries respond to this growing threat?

Based on my experience in nuclear non-proliferation and politics, I argue that African leaders need to proactively confront the risks while there is still time.

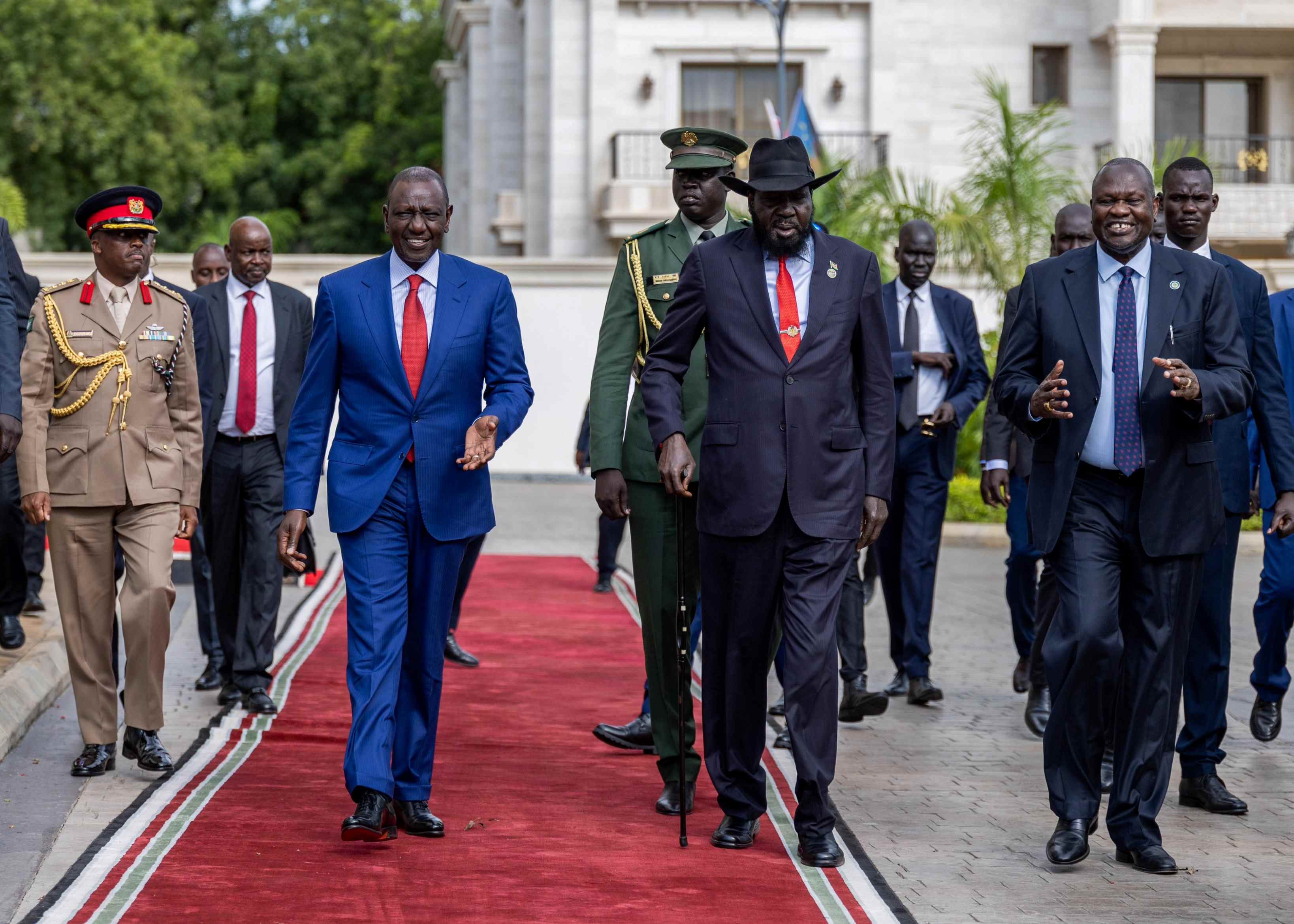

All African states, except for South Sudan, abide by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. This is an international agreement which limits the spread of nuclear weapons. And 43 African states have gone further to join the African Nuclear Weapons Free Zone Treaty (Treaty of Pelindaba). This was negotiated in the belief that it would “protect African states against possible nuclear attacks on their territories”.

As conflict and uncertainty push many Western leaders to support the madness of nuclear weapons proliferation, African leaders are in a unique position to push back against this.

Africa’s strength in numbers in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the Nuclear Ban Treaty, is a vehicle the continent can use to address nuclear weapons risks, head-on.

Global divide

On one side, nuclear-armed states cling to deterrence for their national security. They insist that possessing nuclear arsenals keeps them safe.

At present, there are nine nuclear-armed states: the US, Russia, the UK, China, France, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. These countries possess around 12,331 nuclear warheads (as of 2025).

The use of only 10% of these weapons could disrupt the global climate and threaten the lives of up to 2 billion people.

On the other side, African countries and other non-nuclear-weapon states such as Ireland, Austria, New Zealand and Mexico highlight how deterrence creates unacceptable risks for the entire international community.

This global majority – the 93 countries that have signed the Nuclear Ban Treaty and 73 that are party to it – argue that real safety comes from eliminating nuclear threats.

The Nuclear Ban Treaty became international law on 22 January 2021. It is the first instance of international law challenging the legality and morality of nuclear deterrence.

Since 2022, states parties to the Nuclear Ban Treaty have held formal meetings to address current nuclear risks. In March 2025, at their third meeting, 17 African states officially recognised nuclear deterrence as a critical security concern. They called on nuclear armed states to end deterrence.

The deterioration of the international security environment is so palpable that there has been a noticeable shift in nuclear ban states’ perception of nuclear threats. Nuclear disarmament is no longer just a humanitarian or moral concern to these states, it is now a national security concern.

South Africa warned that any use of nuclear weapons would result in catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would have a global impact.

Ghana likewise stressed that Africa is not immune to nuclear war’s fallout:

Africa, despite its geographic distance from the immediate hotspots of nuclear conflict, is not immune to the repercussions of nuclear weapons.

Africa bears a unique historical connection to nuclear issues. Nuclear testing in the Sahara Desert in the 1960s, when France detonated nuclear bombs in Algeria, had devastating consequences. Widespread radioactive contamination harmed local communities, caused long-lasting health problems, displaced populations, and left large areas environmentally damaged and unsafe for generations.

For its part, Nigeria recalled that Africa had “long acknowledged the existential threat nuclear weapons posed to human existence.”

The meeting determined that it is unacceptable that states parties are exposed to nuclear risks, “created without their control and without accountability”. It stressed that eliminating nuclear risks “is a prime and legitimate concern and national responsibility” of states.

Next steps

Delegates effectively asked whether their own national security concerns had less value than those of nuclear-armed states. I think this is a valid question.

Africa’s leaders and their allies in the Nuclear Ban Treaty are reframing what “national security” means in the nuclear age.

Rather than accepting a world perpetually held hostage by the madness of nuclear deterrence, they are asserting that the security of nations – and of peoples – is best served by dismantling this threat to humanity.

They are prioritising human life, development and international law over the threat of overwhelming force.

The outcome of this contest will have profound implications, not just for Africa but for the entire globe.

Olamide Samuel, Track II Diplomat and Expert in Nuclear Politics, University of Leicester

Top Stories Today