Silent crisis of self-medication and gaps in SHA services for patients with chronic illnesses

Self-medication poses serious risks. Without proper diagnosis, people often take the wrong drugs or doses, which can worsen their illness or cause harm.

For years, Zuhura Abdi, a mother of two, relied on her nearest dispensary for treatment. But the persistent lack of medication at the facility eventually forced her family to turn to self-medication and only seek hospital care when symptoms became too serious to manage at home.

“Most of the time, I don’t even take my children to the hospital,” she admits. “I just ask how they’re feeling, check their temperature, go to the chemist, explain the symptoms, and I’m given medicine. Most times, we recover.”

More To Read

- SHA denies wiring Sh20 million to ghost hospital in Homa Bay, confirms payment to Nyandiwa Level 4

- Hospitals get Sh3.4 billion boost as SHA settles insurance claims

- Lagdera MP demands action as health facilities defy Ruto’s free outpatient care directive

- Garissa residents set to benefit as Balambala Hospital goes digital

- Three charged in Nairobi for posing as SHA officials to defraud patient’s family

- Nairobi Hospital suspends fee hike after insurance pushback

Apart from self-medication, Zuhura has also faced challenges receiving services during her antenatal care visits. Without registration under the Social Health Authority (SHA), she was denied services and turned away. Forced to pay Sh30 to register for SHA, she hoped this would unlock better care, but nothing changed.

“I even made the premium payment, thinking services would improve at the dispensary near me,” she says. “But there’s no difference. Whether you’ve paid or not, the medication is still unavailable.”

She continues to buy medicine out of pocket. “The only thing taking me to the hospital now is the baby’s vaccine. Everything else, I have to purchase, and it doesn’t make sense.”

Zuhura also notes that other private hospitals near her home do not accept SHA, while long queues at public Level 4 hospitals often discourage her, especially when the illness isn’t severe.

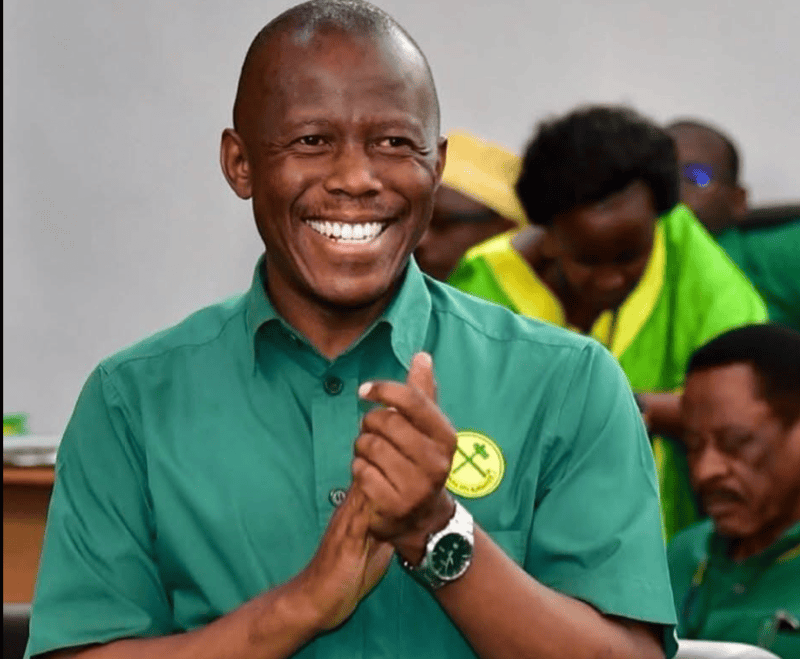

Zuhura Abdi, a mother of two, relied on her nearest dispensary for treatment. (Charity Kilei)

Zuhura Abdi, a mother of two, relied on her nearest dispensary for treatment. (Charity Kilei)

Sarah Wangui, another patient who was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2024, turned to SHA, hoping it would provide a lifeline. Instead, she found limits, delays, and dead ends.

“I used up my SHA limit by February. Since then, I haven’t had consistent chemotherapy sessions. Each one now costs more than Sh150,000, and I can't afford it.”

The SHA, designed to provide universal health coverage, only pays for three chemotherapy sessions.

For patients like Wangui, living with advanced cancer, that is nowhere near enough. Once the limit is reached, patients are left to fend for themselves.

Her fight with cancer began in 2015, when she was diagnosed with Stage 3B breast cancer. Then a working mother and wife, she was managing a career and raising a young child. The diagnosis upended her life.

After undergoing chemotherapy and a mastectomy, her doctors declared her cancer-free by the end of 2016. But the relief was short-lived. Months later, during a routine follow-up, the cancer returned — this time, more aggressive.

She went through another mastectomy and several rounds of treatment, funded in part by well-wishers and the now-defunct NHIF. Once again, she fought with determination, clinging to the hope of a full recovery.

But in late 2024, her health deteriorated. “I started having trouble breathing. I thought maybe it was pneumonia.”

Tests revealed the cancer had spread to her lungs. Doctors drained nearly 0.7 litres of fluid from her chest. The diagnosis was a devastating setback.

Now receiving treatment at Kenyatta National Hospital, she is growing weaker by the day. With no income and no remaining SHA coverage, her treatment has become inconsistent.

“I don’t work. I depend on well-wishers,” she says. “And now I have to wait for the new fiscal year before any new government funds are released. Until then, I’m stuck.”

Her only relief comes from strong painkillers — opioids prescribed to manage the growing discomfort in her chest.

Wangui’s story is just one among thousands in Kenya. As the SHA rolls out across the country, patients with chronic conditions like cancer are finding themselves excluded from meaningful, sustained care.

Over-the-counter drugs

Self-diagnosis and over-the-counter medication have long been a challenge in Kenya’s healthcare system — a symptom of deeper issues tied to inequality and inaccessibility.

Amina Abdikadir, a pharmacy attendant in Nairobi, has seen all kinds of patients walk through her doors. In her experience, medication is often sold based on demand rather than medical need, with the most frequently requested drugs taking centre stage on the shelves.

She notes that prescriptions are rare. “Most people come in, describe their symptoms, and then ask for a specific drug. While some are open to guidance and questions, the majority insist they know exactly what they want — which is dangerous.”

What concerns her most is that this self-diagnosis and self-treatment approach cuts across all demographics. Both men and women, young and old, come in to buy medication not only for themselves but also for their children or elderly family members. The pattern is consistent.

“In most cases, the people buying medicine haven’t visited a health facility to know what’s actually wrong. They’re treating symptoms based on guesswork. Most are buying painkillers and antibiotics without any lab tests or doctor consultations,” she says.

Amina fears that this widespread reliance on pharmacies as substitutes for professional care, often driven by cost, inaccessibility, or frustration with the public health system, is putting countless lives at risk.

“It’s a silent crisis. People are medicating in the dark, and many don’t even realise the harm they could be doing, many preferring cheaper drugs compared to expensive ones.”

Self-medication poses serious risks. Without proper diagnosis, people often take the wrong drugs or doses, which can worsen their illness or cause harm.

It delays professional care, risks complications, and masks serious conditions. Misuse of antibiotics fuels resistance, while buying medicines without guidance wastes money and can lead to addiction or toxicity. In places with weak regulation, self-medication also increases the chance of consuming fake or poor-quality drugs.

Top Stories Today