‘We were told not to cry’: The untold mental health crisis facing Kenya’s men

Like many others in his situation, Erick Mwari turned to substances to cope, numbing emotional pain with harmful distractions.

In 2015, Erick Mwari was only 10 years old when the world around him collapsed. His mother had died, and when his father remarried, Mwari was left behind—abandoned and alone.

With no one to care for him, no home to return to, and no hand to hold, he was forced to survive the harsh streets of Nairobi, carrying a weight no child should ever have to bear.

More To Read

- Senate urges swift action on Kenyans stranded in Russia, gender violence, mental health, and illegal construction

- Beyond the numbers: Why Kenya’s teenage pregnancy crisis demands new conversations

- MPs push to scrap law criminalising suicide attempts in Kenya

- From grief to action: How widow is changing Kenya’s battle against NCDs

- Kenya to conduct first national mental health survey under new advisory committee

- Groundbreaking trial finds single dose of LSD eases anxiety

As a young boy, Mwari endured constant physical abuse, bullying, and isolation. But the deepest wounds were invisible.

The loneliness, fear, and uncertainty about the future weighed heavily on his mind.

“I had no one to talk to. Life was just about survival or finding a place to sleep. As a young person on the streets, you barely have any direction—just drugs,” he recalls.

Like many others in his situation, he turned to substances to cope, numbing emotional pain with harmful distractions.

At Kamukunji Grounds—an open space where many unemployed men would gather—Mwari observed the despair of idleness and hopelessness.

“When you’re young and on the streets, people look down on you,” he says.

“Many don’t care. It’s hard to open up because people assume you’re just ‘bad and you become angry at the world.”

Invisible, dehumanised

The stigma of street life compounded his mental health struggles, leaving him and many others feeling invisible and dehumanised.

Carrying only a few belongings and no stable shelter, Mwari lived with the constant stress and trauma of survival. With no safety net, envisioning a better future seemed impossible.

But in 2020, Mwari’s life began to change. He became a beneficiary of a mental health support programme initiated by the Kamukunji Environment Conservation Champions (KECC)—a grassroots coalition of 25 community-based organisations working in Pumwani Ward.

The initiative recognised that even men who appeared stable or well-dressed were silently carrying enormous psychological burdens.

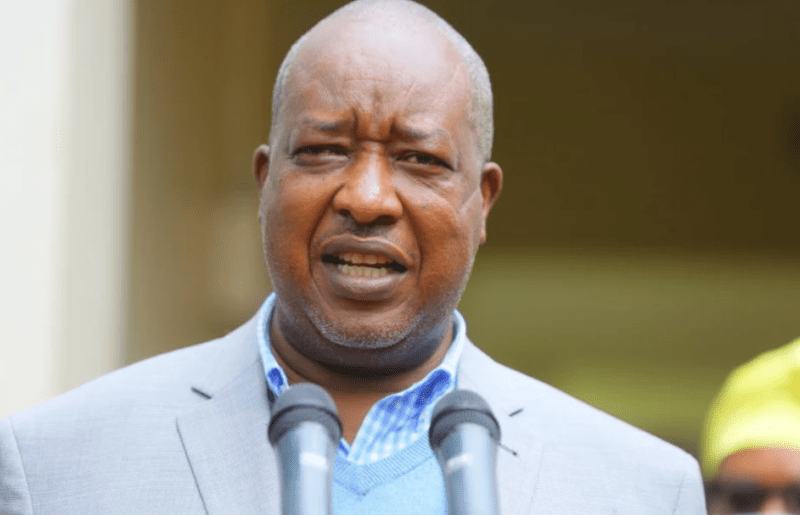

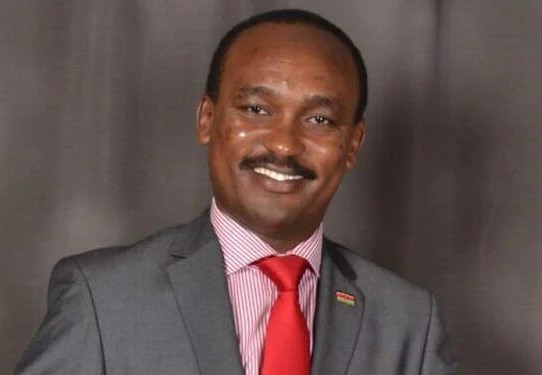

Mohammed Kioko, the vice chairman of Kamukunji Environment Conservation Champions. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Mohammed Kioko, the vice chairman of Kamukunji Environment Conservation Champions. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Other Topics To Read

The counselling and support Mwari received gave him his first tools for healing.

“Though there are still things I’m not comfortable sharing, at least now I have some guidance,” Mwari says.

Today, he works at Gikomba Market carrying goods—a modest but meaningful step toward stability.

“We would just talk, and they would advise me. I took the advice.”

Vibrant community hub

KECC Vice Chairman Mohammed Kioko has been instrumental in driving the community-based response to mental health in Kamukunji. The organisation’s efforts began by reclaiming a neglected public space—once overgrown with bushes and garbage—and turning it into a vibrant community hub.

In 2020, KECC transformed the area into a safe, inclusive space for relaxation and conversation. They established distinct zones, including a children’s play area, a “Wall of Fame” to celebrate local heroes, and a mental health corner, born from a pressing need.

“We noticed many men would come and sit here all day, some even sleeping on the ground, they weren’t just tired—they were emotionally exhausted. Many had lost jobs, couldn’t go home, or felt crushed by expectations they couldn’t meet.”

Through open discussions, the team began to uncover the hidden emotional battles these men were fighting.

“Some told us they were depressed. Others were angry, struggling with family pressure, separation, infidelity, or financial constraints. Some even left home entirely because they felt they were failing as men.”

Peer support

The mental health corner became a space for peer support, where men could speak honestly without fear of judgment.

“Society tells men not to cry, not to talk about emotions. But that silence is killing us,” Kioko says.

Kioko shares the tragic story of a Ugandan man who regularly visited the space.

“He used to carry goods at the market. He never opened up—just sat and chewed miraa in silence. Then, one day, we heard he had taken his own life. We only found out what he was going through too late.”

Such tragedies are, unfortunately, not isolated.

“We’ve seen cases where men harm themselves or others because they’ve kept too much inside. That’s why we try to talk to one another and break the silence.”

To strengthen support, KECC has partnered with the county and national governments.

“Sometimes therapists are sent to us, and when we encounter cases we can’t manage, we refer people to professional help,” says Kioko. “We do monthly check-ins to identify those at risk and make sure they’re not alone.”

Human connection

Through community leadership, open dialogue, and grassroots compassion, KECC is creating a new model—one that offers healing not just through treatment, but through human connection.

“We don’t have to fix everything overnight. But if we can just start by talking, that’s already a powerful step,” Kioko says.

For many men living on the streets, the struggle with mental health is often silent, invisible, and deeply misunderstood.

Counselling psychologist Daisy Khaindi has seen firsthand how societal expectations make it harder for men to seek the help they need.

“Men find it especially difficult to admit when they’re struggling,” she explains. “Even when experiencing serious mental health conditions like psychosis, many suffer in silence. They rarely open up, and instead, often turn to unhealthy ways of coping.”

She believes that societal pressures around masculinity play a major role.

“Due to expectations about being providers and always appearing strong, many men would rather live on the streets than talk about their vulnerabilities. There’s a stigma around being seen as weak, especially if they’ve lost a job or can’t support their families.”

Substance abuse

Among these coping mechanisms, substance abuse is common.

Khaindi notes that for some men, addiction becomes a way to escape emotional pain or manage feelings of shame and failure. But this path often leads them deeper into instability—and in many cases, onto the streets.

The reluctance to seek help is stark. Khaindi estimates that only one in 20 men pursue therapy or mental health support, with most only reaching out during times of extreme crisis.

She emphasises the need for stronger support systems tailored to men—spaces where they can speak openly, without fear of judgment.

These challenges are not just anecdotal—they are reflected in national data.

Homeless population

According to a report by the National Council for Population and Development (NCPD), men make up the majority of Kenya’s homeless population.

The findings, published in the Sessional on the Kenya National Population Policy for Sustainable Development, show that eight out of every 10 homeless individuals are male.

Eighty per cent of Kenya’s homeless are men, equating to 42 individuals for every 100,000 in the population. Nairobi County currently has the highest number, with 15,337 homeless people. Other counties with significant numbers include Mombasa (7,529), Kisumu (2,746), Uasin Gishu (2,147), and Nakuru (2,005).

The scale of the crisis is growing. While the 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census recorded just over 20,000 homeless people, the most recent data now places the number at over 46,000—a more than twofold increase.

Mental health continues to carry a heavy stigma, particularly for men, who are often pressured by societal norms to appear emotionally strong and unshaken. In Kenya, these expectations have led to serious consequences.

A 2022 report by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) revealed that mental health disorders affect more men than women, 56.9 per cent of men compared to 43.1 per cent of women.

One of the most troubling signs of this crisis is the country's suicide statistics. In 2021 alone, more than 130,000 Kenyan men died by suicide, significantly higher than the approximately 100,000 women who did.

Despite these sobering figures, mental health services remain severely underutilised, particularly by men. Estimates suggest that over 60 per cent of men living with mental illness in Kenya do not seek help, largely because of the stigma surrounding mental health and the cultural belief that showing vulnerability is a sign of weakness.

Top Stories Today