'We feel forgotten': People living with HIV decry stigma as US aid cuts bite

Patients and experts alike warn that the once-celebrated progress in HIV management is now unravelling, leaving vulnerable groups to fend for themselves.

Harrowing accounts are emerging from Kenyans living with HIV, who say they are sliding back into fear, stigma and hopelessness following months of uncertainty since the withdrawal of United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding early this year.

A section of them now accuse the government of dragging its feet in finding alternative support to sustain treatment and care programs that millions depend on for survival.

More To Read

- Male circumcision is made easier by a clever South African invention - we trained healthcare workers to use it

- Peace at risk: Counties urged to fill funding void after USAID exit

- Kenya sees alarming rise in HIV infections after years of decline

- How Kenya's adoption of single-dose HPV vaccine could boost fight against cervical cancer

- Kenya records over 20,000 new HIV infections in 2025 as Nairobi leads in cases

- Africa CDC, UNAIDS sign deal to strengthen HIV response, epidemic preparedness

Patients and experts alike warn that the once-celebrated progress in HIV management is now unravelling, leaving vulnerable groups to fend for themselves.

The delay in cushioning donor-funded programs, they say, has not only disrupted treatment but also rekindled stigma, something they thought had been buried decades ago.

“The feeling is that we are being abandoned,” said 25-year-old Julie, not her real name, from Dandora, Nairobi.

Diagnosed with HIV at 18, she rebuilt her life through counselling and consistent treatment under a USAID-supported program.

But when the funding was frozen in February this year, panic set in.

“I received so many calls from people asking if I’d seen the news. I switched off my phone, I couldn’t take it,” she narrated.

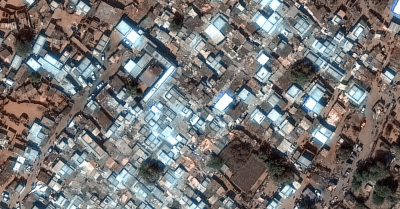

Across the country, the impact was swift and brutal. Clinics began rationing antiretroviral (ARV) drugs, with some running out entirely.

Patients who once received six-month prescriptions were forced to scale down to just one-month supplies, while others were forced to buy drugs from informal sellers for up to Sh1,500 per bottle.

Even basic commodities like condoms and testing kits began vanishing from public facilities.

“I have missed my cervical cancer screening for the first time in years. Everything just stopped,” Julie added.

“As a woman living with HIV, I must get cervical cancer screening every year. I’ve missed mine since February.”

On their side, health experts say the crisis exposes the fragility of Kenya’s HIV response, which has for decades relied heavily on donor support through USAID and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

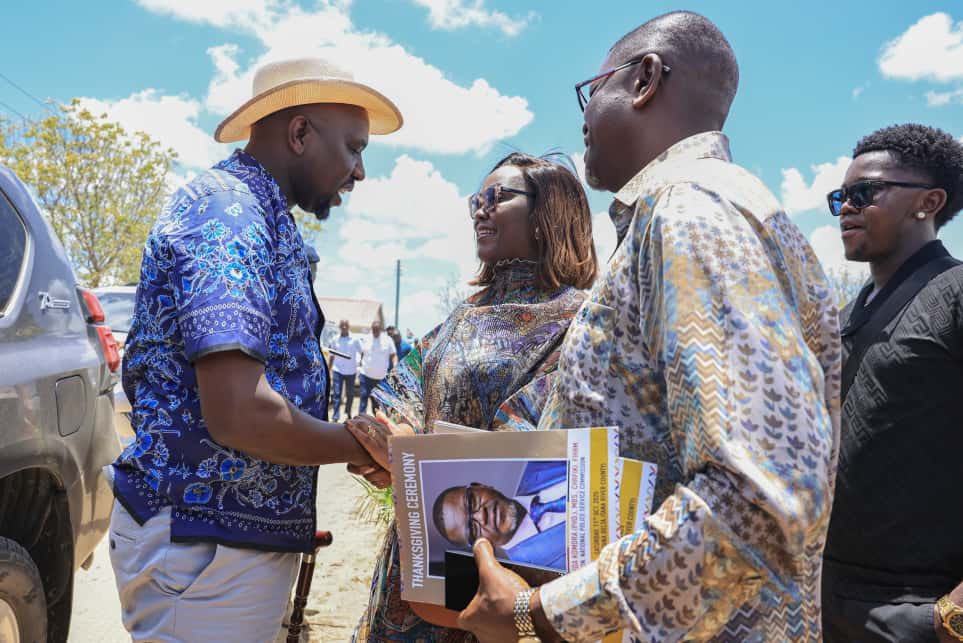

“The freeze exposed how dependent we are,” said Nelson Otuoma, CEO of the National Empowerment Network of People Living with HIV (NEPHAK).

“Even patient data systems were donor-funded; once they went offline, hospitals lost access to crucial records.”

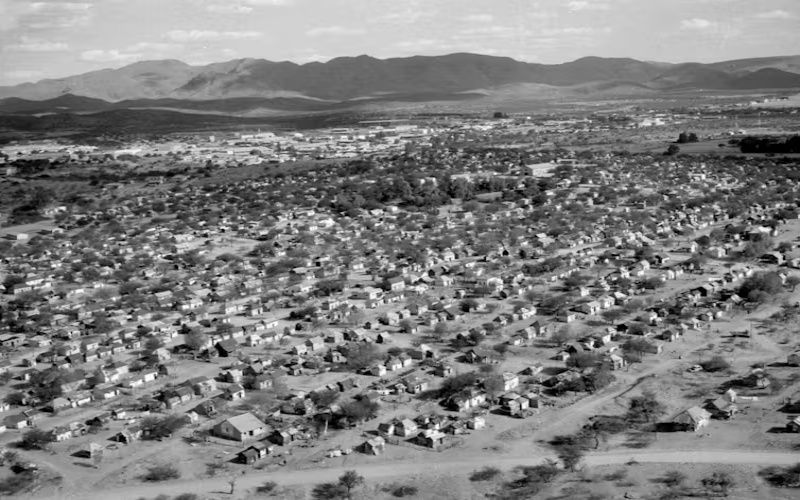

In Kilifi County, one of Kenya’s HIV hotspots, the human toll is equally stark.

At his modest home in Mnarani, 65-year-old Jacob, also not his real name, recalls the early years of the epidemic when stigma was as deadly as the virus itself.

“We buried people in plastic bags,” he said quietly.

Two decades later, he now watches history threaten to repeat itself, warning that if programs shut completely, the young people will be the first victims.

County health officials highlight that nearly 90 per cent of Kilifi’s HIV services relied on USAID’s Stawisha Pwani program, which supported treatment, prevention, and gender-based violence interventions.

With the cuts, they reckon that key activities have halted, and nutrition support for children living with HIV has been suspended.

“I have two child patients with high viral loads; they can’t even afford transport to the clinic,” said counsellor Selinah Anyango at Muyeye Health Centre near Malindi.

To bridge the gap, the government has since begun integrating HIV care into general hospital services, a move officials say is meant to ensure continuity.

However, a section of the sector experts argues the approach has yet to gain patient trust.

“The integration plan sounds promising, but people living with HIV need dedicated spaces where they feel safe and not judged,” said Kilifi County preventive health coordinator Amos Nthenge. “Once those spaces close, stigma returns.”

Beyond the human pain, the economic implications are staggering. Over 41,000 healthcare workers across the country, mostly on donor-funded contracts, remain at risk of losing their jobs.

“If you invest for 20 years and then pull out, everything collapses,” Otuoma said. “We celebrated two decades of PEPFAR in 2024, and a year later, we are watching the system crumble.”

Back in Dandora, Julie has found a new purpose in advocacy. Along with other young mothers, she runs podcasts and social media campaigns to raise awareness on stigma, resilience, and accountability.

“We can’t sit and wait for rescue. We must speak up and remind everyone that our lives matter.”

Top Stories Today