Beyond the numbers: Why Kenya’s teenage pregnancy crisis demands new conversations

Isaack believes real change will only come when both genders are included in the conversation — when young men are taught empathy, respect, and shared responsibility.

The stigma surrounding teenage pregnancy continues to weigh heavily on many young girls across Kenya. Despite years of awareness campaigns and government interventions, the numbers remain alarming.

In 2024 alone, more than 250,000 teenage pregnancies were reported, according to the Ministry of Health — a figure that underscores both a public health and social crisis.

More To Read

- Education Ministry sets up special unit to tackle teenage pregnancy in schools

- Kenya set to miss 2025 target as teen pregnancies persist

- From grief to action: How widow is changing Kenya’s battle against NCDs

- Barriers to care: How systemic failures endanger teenage mothers in Kenya

- Africa's youth may feel lonelier than you know

- Grassroots football in Kwale helps girls tackle teenage pregnancies and child marriages

Behind every statistic lies a story of shame, silence, and lost opportunity. In many Kenyan households, talking about sexual and reproductive health (SRHR) remains taboo — an unspoken topic left to chance or curiosity. Parents often assume that silence equals discipline, but in truth, it leaves adolescents vulnerable and uninformed.

Many young people learn about sex and relationships from peers or social media, where information is rarely accurate or age-appropriate. Without open guidance, misinformation flourishes, and curiosity often leads to risky behaviour.

For 19-year-old Leilah Hussein from Nairobi, her teenage years were marked by confusion and fear. She never learned about menstruation, relationships, or contraception from her parents. Instead, her peers and social media became her teachers.

Taboo

The subject of sex was taboo in her home. Any hint of curiosity was met with reprimand. That silence, she says, didn’t protect her — it only made her more curious.

“It's hard to even say you're pregnant — most girls just get married quietly when it happens,” Leilah says, her voice low and deliberate.

In her community, young mothers are often treated as outcasts. Some are insulted by their families; others are hurriedly married off to “save face.” Very few are allowed to continue their education. The fear of rejection runs so deep that many girls hide their pregnancies until it’s too late to seek help.

Leilah recalls how her friends used to whisper about girls who became pregnant — they were shamed, blamed, and forgotten.

“Teen pregnancy means you've wronged yourself,” she says. “You carry the shame alone.”

While most conversations around teenage pregnancy focus on girls, 20-year-old Isaack, a youth advocate from Kisumu, believes the silence surrounding boys is equally harmful.

He argues that the way society raises boys — to suppress emotion, avoid accountability, and equate masculinity with conquest — has worsened the problem.

“The idea sold to us is that pregnancy is a woman's issue — her body, her problem,” Isaack says.

Not understanding consequences

He explains that many boys grow up without understanding the consequences of their actions. Peer pressure becomes their invisible teacher.

“Among young men, you're respected by how many girls you've been with,” he says. “When a pregnancy happens, the girl is blamed, while the boy moves on. That's not just unfair — it's dangerous.”

Isaack believes real change will only come when both genders are included in the conversation — when young men are taught empathy, respect, and shared responsibility.

For Liz Marie, a university student from Mombasa, the teenage pregnancy crisis goes beyond personal choices or moral decline — it is rooted in structural inequality.

Underserved areas

She points out that most teenage mothers come from underserved areas where poverty, unemployment, and lack of access to education leave girls vulnerable.

“If a girl has access to education, basic needs, and financial support, she's less likely to be pressured into risky behaviour,” Liz says.

In such communities, transactional relationships are common. Some girls engage in sexual relationships with older men in exchange for money, food, or school supplies.

The Covid-19 pandemic worsened this, pushing families deeper into poverty and leaving girls without school supervision or protection.

Liz argues that addressing teenage pregnancy requires a holistic approach — one that combines sex education with economic empowerment, mentorship, and safe spaces for girls to dream and thrive.

“The conversations shouldn't just happen in conferences or churches,” she adds. “They need to reach the villages, the estates, and the schools where girls and boys live these realities every day.”

Faith communities have often been accused of perpetuating silence around reproductive health, but some are now working to change that.

Reframe sex and gender conversations

At a recent interfaith discussion in Nairobi, Sheenah Mbau, Programme Manager of the Faith Action Network, spoke about a growing movement among faith leaders to reframe conversations around sexuality and gender.

Her organisation, which brings together Christian, Muslim, and interfaith leaders, works across three thematic areas — peacebuilding, inclusion of people living with HIV, and gender justice.

Through these initiatives, they directly engage young people on issues of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) — a topic once considered taboo in religious spaces.

“Faith can help reframe the conversation — to include boys, parents, and the entire community,” Sheenah says.

Through partnerships with groups like SUPKEM (Supreme Council of Kenya Muslims) and other interfaith coalitions, they are developing faith-led approaches to sex education.

These include discussions on consent, contraception, and the value of gender equality, particularly in counties such as Samburu, Kilifi, and Narok — regions where nearly half of teenage girls have experienced pregnancy.

Mbau says these conversations are not about encouraging immorality but about promoting informed choices and mutual respect.

“We want to go beyond awareness and look at what's driving this — the silence, the shame, and the social norms,” she says.

For James Okumu, a faith-based leader from Nairobi and a father of three, the solution to teenage pregnancy must begin at home.

He recalls growing up in a household where sex was never discussed — a silence he later realised was common among parents in his congregation. But Okumu believes that silence is no longer an option.

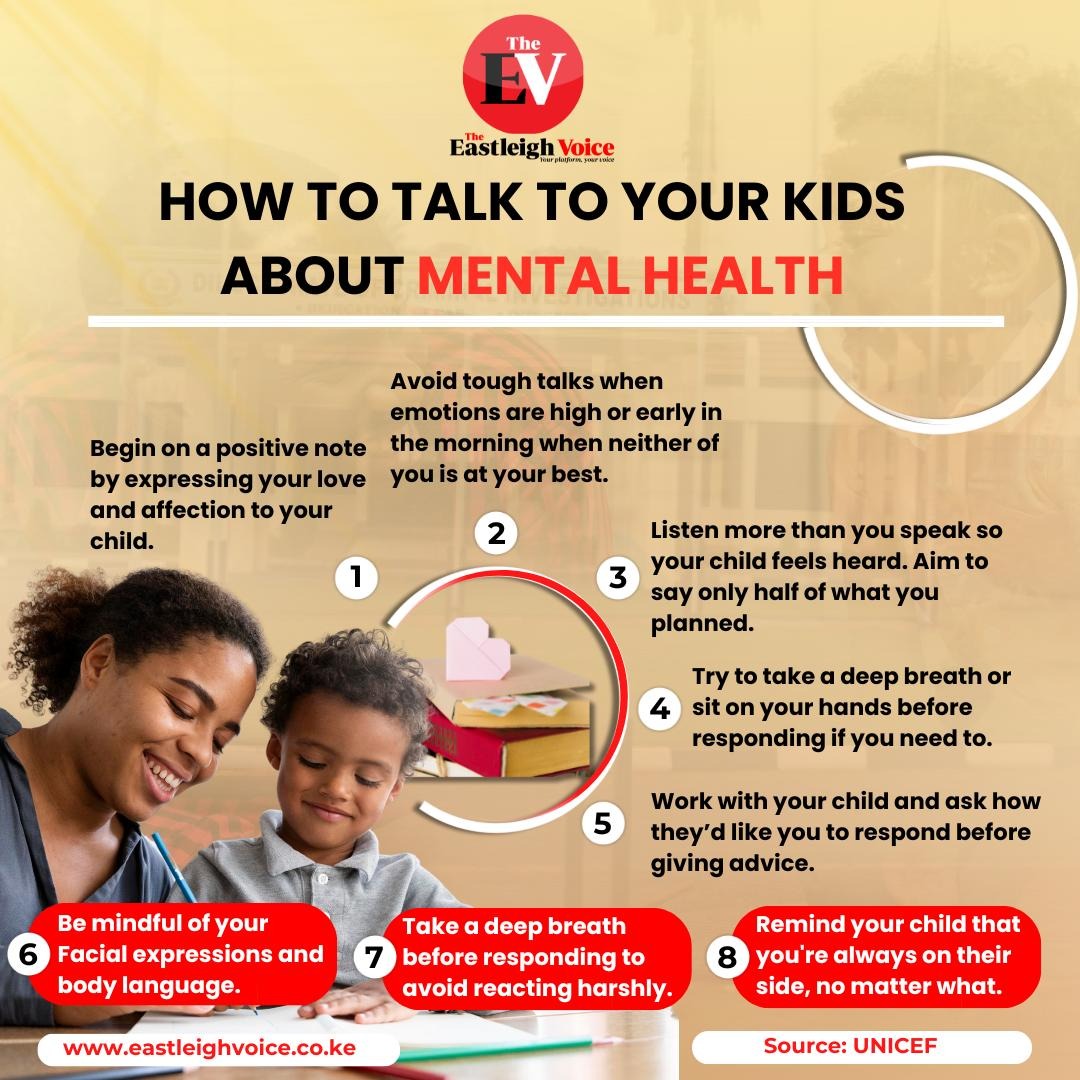

“Parents can find simple, respectful ways to talk to their children about these issues,” he says. “If we don't talk, the internet and peers will — and they rarely teach the truth.”

Times have changed

Okumu notes that many parents still fear that discussing sexuality will “corrupt” their children or make them curious. But he argues that times have changed. In today’s digital age, children are often exposed to adult content long before they are emotionally ready to handle it.

“Our parents thought talking about sex would make children curious, but today, children already learn about it through the internet — if we don't guide them, they'll get half-truths,” he explains.

To bridge that gap, Okumu and his church have launched mentorship circles where young people meet trained mentors to talk about life skills, body respect, faith, and healthy relationships. These discussions, he says, are not meant to replace parental guidance but to strengthen it.

“We realised many parents don't know where to start — so we help them learn how to approach these conversations at home,” he adds.

Begin talks early

He advises parents to begin such talks early — not as warnings or threats, but as open, honest conversations.

“Start by teaching children about respect — for their bodies, their emotions, and others,” he says. “When that foundation is strong, the rest becomes easier.”

Okumu also urges fathers to take a more active role.

“Fathers need to be present, not just as providers, but as listeners and guides,” he says. “When a child feels safe asking their father about tough topics, that's where true mentorship begins.”

Beyond the home, Okumu believes faith communities must move from judgment to compassion.

“The faith must evolve — from condemning mistakes to supporting those who fall,” he says. “We've raised men who don't take responsibility. If the boy gets a girl pregnant, it's her problem — she carries the shame while he moves on. That has to change.”

Empathy

For him, breaking the cycle begins with empathy — teaching children that every action has consequences, but also that every mistake can become a moment for learning and restoration.

“When we create safe spaces — at home and in church — our children will talk to us before the world misleads them,” he says.

Kenya continues to grapple with alarmingly high rates of teenage pregnancy, a challenge that cuts across both rural and urban communities.

In 2024, more than 241,000 adolescent girls aged 10 to 19 were recorded as having attended their first antenatal clinic visit, according to national health data. While this represented a slight 4.8 per cent decline from the previous year, the figures remain deeply concerning.

Among the reported cases, 10,126 pregnancies involved girls aged 10 to 14, while 231,102 were among those aged 15 to 19. These numbers reveal not only the scale of the crisis but also how early many Kenyan girls are being exposed to sexual activity — often without adequate information or protection.

Teenage pregnancies in Nairobi

In Nairobi County, teenage pregnancy remains a pressing issue despite its urban setting and greater access to education and health facilities.

The county accounted for about 6.1 per cent of all reported adolescent pregnancies in 2024, placing it among the top counties with the highest cases.

Reports also indicate that Nairobi recorded over 450 cases among girls aged 15 to 19 during one reporting period — proof that the problem is not confined to rural areas.

The Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2022 showed that 15 per cent of girls aged 15 to 19 had already been pregnant at least once — a modest drop from 18 per cent in 2014. However, this national average conceals sharp regional disparities.

In counties such as Samburu, Kilifi, and Migori, nearly half of adolescent girls have experienced pregnancy, while in others, the prevalence remains below 10 per cent.

Globally, Kenya’s adolescent fertility rate remains among the highest. As of 2020, the country recorded approximately 72 births per 1,000 girls aged 15 to 19, compared to a global average of about 44 births per 1,000. This places Kenya among the countries with the highest rates of teenage pregnancy worldwide — and among the top five in sub-Saharan Africa.

Top Stories Today