Kenya’s silent crisis: How blood shortages are driving maternal deaths

According to the WHO, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a leading cause of maternal deaths worldwide, responsible for approximately 70,000 deaths annually.

In Kenya, about three out of every ten women die from postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) every day due to the unavailability of blood at the critical moment of need. This silent crisis is unfolding in hospitals and health facilities across the country.

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a serious and often life-threatening condition that occurs when a woman experiences excessive bleeding after giving birth. While it’s normal for some blood loss to happen during delivery, PPH is diagnosed when the bleeding becomes severe - typically more than 500 millilitres after a vaginal birth, or more than 1,000 millilitres after a caesarean section.

More To Read

- Two men charged with stealing Sh1.1 million in blood collection kits from Kenyatta National Hospital

- Rewriting blood donation story: How Mombasa nurse is saving lives through mobile app

- Oluga calls for urgent reforms in blood services to avert crisis, boost UHC goals

- Wajir residents urged to donate blood as shortage hits county referral hospital

- Haemophilia association calls for government funding to address treatment gaps

- Kenyan mothers struggle for survival, dignity and care in shadow of haemophilia

PPH can happen within minutes after childbirth, but it can also occur up to 24 hours later or even days after delivery. It is a tragedy that continues to claim lives, not because the bleeding cannot be managed, but because blood is unavailable when most needed.

According to health experts, blood is essential during postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) because heavy bleeding rapidly reduces blood volume, leading to shock and potential organ failure. Replacing lost blood helps maintain blood pressure and ensures oxygen delivery to vital organs.

Additionally, transfusions supply critical clotting factors needed to stop bleeding. Timely blood replacement is key to preventing severe complications and saving lives. This chronic shortage of blood not only results in preventable maternal deaths but also places newborns at risk and destabilises families and entire communities.

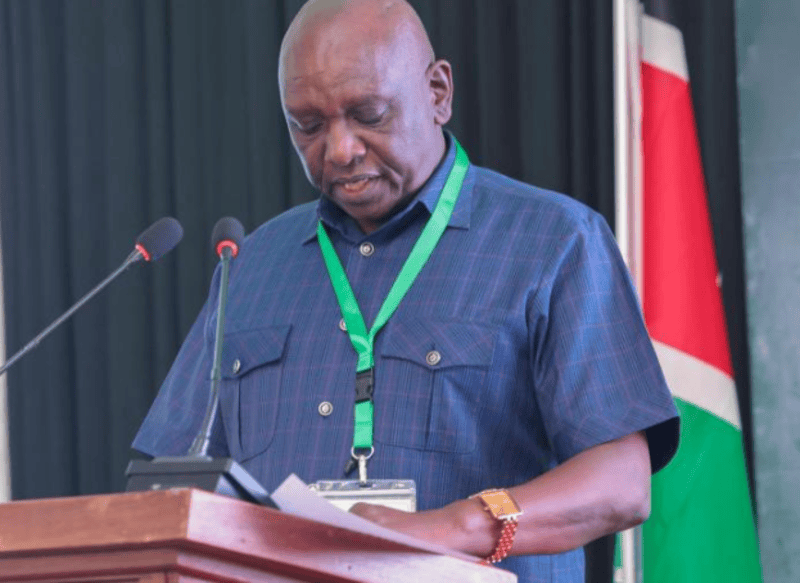

Speaking at the launch of the 'Run for Her' campaign to end postpartum haemorrhage in Nairobi, which will be held in nine countries in Africa and conducted across five counties in Kenya, Dr Kireki Omanwa, the President of the Gynaecological and Obstetrical Society, emphasised the devastating impact of maternal deaths on newborn survival.

The President of the Gynaecological and Obstetrical Society, Dr Kireki Omanwa, speaks during the launch. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

The President of the Gynaecological and Obstetrical Society, Dr Kireki Omanwa, speaks during the launch. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

“When a mother dies during childbirth, her baby’s chance of survival drastically diminishes. In Kenya alone, we lose over 5,000 women and newborns each year - many due to the lack of safe and timely blood transfusions. It is a heartbreaking reality that, 63 years after independence, Kenya still grapples with this preventable failure in its healthcare system.”

Dr Omanwa said the maternal health crisis is a profound societal failure, as no woman should lose her life in the process of giving life. "This urgent call to action highlights the critical need for strengthened healthcare systems, timely interventions, and access to safe blood transfusions to save mothers and their babies."

According to Professor Moses Obimbo, Africa accounts for 30 per cent of global births but bears more than 50 per cent of the world’s maternal health challenges. In 2023 alone, the continent recorded a staggering 182,000 maternal deaths. Of these, more than 100,000 were due to postpartum haemorrhage.

In Kenya, 240,000 teenage pregnancies were reported during the same year, increasing risks for poor pregnancy outcomes, severe PPH, high blood pressure, infections from unsafe abortions, and adverse outcomes for newborns.

Obimbo said weak emergency preparedness, low community engagement, and poor health system responsiveness deepen the maternal health crisis.

“Postpartum haemorrhage alone causes 35 to 60 per cent of maternal deaths. It is 1.6 times deadlier than road traffic accidents. Yet two to three women die every day in Kenya, not because the bleeding couldn’t be managed, but because we didn’t have blood,” said Obimbo.

A quarter of maternal deaths from PPH in Kenya are directly due to the lack of available blood. Many health facilities do not have the infrastructure to store blood, and even where storage is available, the supply remains critically low. Of the 460 units of blood typically collected during donation campaigns, 75percent is used by women, particularly in childbirth emergencies.

Wilson Owino Opondo, a Public Health Manager with the Kenya Red Cross Society, emphasised that the key to managing postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) - a leading cause of maternal mortality - is timely access to blood.

Delegates pose for a photo during the launch. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Delegates pose for a photo during the launch. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

"Blood is the treatment for postpartum haemorrhage. Whenever a woman presents at a health facility and ends up developing complications during labour, there is a high risk of PPH," said Opondo.

Opondo pointed out that several factors contribute to maternal deaths, especially among young girls and women with limited access to sexual and reproductive health services.

"Teenage pregnancies, for instance, often lead to birth-related injuries and tears, which can result in profuse bleeding. Similarly, harmful practices like female genital mutilation (FGM) increase the risk of complications during childbirth," he said.

He highlighted that solving the blood shortage is not just a clinical issue but a community one.

"As we address the issue of blood, we must also tackle its root causes. Blood is the treatment for PPH, and we must raise awareness about it. Women make up the majority of our workforce, and we need to mobilise communities - especially men - to support blood donation campaigns and become allies in saving lives."

Opondo stressed the importance of community engagement as a tool for increasing blood availability.

Bradley Namlanda, a blood mobilizer with Nairobi County, echoed these sentiments, noting that myths and misconceptions significantly hinder regular blood donation. "Some people believe blood is sold, others are held back by superstitions or cultural beliefs. Most people only show up to donate during emergencies, which is not sustainable and weakens the blood bank system."

Namlanda added, "Regular blood donation is essential. The treatment for PPH is blood, and when we don’t have enough, our mothers suffer. We need to change this narrative."

He clarified that all donated blood is screened thoroughly in collaboration with the Kenya National Blood Transfusion Service. "People with chronic illnesses are assessed, and we also help donors know their blood groups during these drives."

Delegates follow talks during the launch of the "Run for Her" campaign to end postpartum haemorrhage in Nairobi. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Delegates follow talks during the launch of the "Run for Her" campaign to end postpartum haemorrhage in Nairobi. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Namlanda emphasised that men can donate blood up to four times a year (every three months), while women can donate up to three times annually. He urged members of the public to participate in the upcoming PPH Run at Ulinzi, which aims to create awareness and mobilise blood donations for mothers in need.

“We encourage all Kenyans to come out, run for her, and donate blood for our mothers, sisters, and loved ones.”

Dr Silvia Kariuki, a paediatrician and neonatologist with Nairobi County, highlighted the ripple effect of PPH on families and communities.

"Postpartum haemorrhage affects not just the mother but the entire family. When a mother dies, the newborn is left without care, and that separation has a lasting impact. Sometimes, even with medical intervention, mothers die because there's no blood. When there's no mother, the baby's chances of survival also drop. It’s a devastating loss," she said.

Dr Kariuki stressed that more people need to realise their power to save lives. "We need consistent, voluntary blood donors - even when there's no immediate need. Understanding the impact of PPH goes beyond clinical management. Losing a mother figure is deeply disruptive. The emotional, psychological, and financial toll on families is long-lasting."

She added, "Let’s think of the children left behind when a mother dies due to PPH. How can we support these babies and families to avoid repeating the same painful losses? Let’s run, let’s donate, let’s rally together - to end PPH."

According to the WHO, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a leading cause of maternal deaths worldwide, responsible for approximately 70,000 deaths annually. In response, Kenya has introduced initiatives such as roaming blood banks in both rural and urban areas to boost blood supplies and improve access to life-saving transfusions.

Top Stories Today