Sweet but dangerous: How junk food hooks kids’ brains and fuels lifelong cravings

Researchers warn that children are prime targets for junk food marketing because they respond emotionally to adverts and can influence household buying decisions.

That packet of crisps or colourful cupcake might seem like an innocent treat, but scientists are increasingly warning that junk food is not just unhealthy—it may be addictive, especially for children.

A new study, published on July 25, 2025, in Nature Medicine by experts including Dr Erica M. LaFata and Dr Nora Volkow (Director of the NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse), calls for addiction to ultra-processed foods (UPFs)—such as crisps, to be formally recognised as a public health concern with addiction-like effects.

More To Read

- Report finds added sugar in Nestlé baby cereals across Africa

- Study shows women under 50 face higher risk of colon growths from ultra-processed foods

- Between belief and medicine: How traditional remedies shape healthcare choices in Kenya

- Childhood obesity on the rise in Kenya: Experts warn of lifestyle, diet and cultural triggers

- China flagged as key source of tobacco imports as Kenya imposes ban to curb youth addiction

- Recipe: How to make salt and vinegar crisps at home

The findings are a wake-up call for parents, policy-makers, and healthcare professionals.

“Certain ultra-processed foods can trigger addictive behaviour consistent with substance use disorders,” the authors argue, citing neurobiological evidence showing that these foods stimulate the brain’s reward systems in ways similar to addictive drugs like nicotine and cocaine.

How sweet treats hook the brain

The study explains how the food industry has perfected the science of hyper-palatability—the precise mix of salt, sugar, and fat that makes the brain crave more. These foods are designed to deliver instant pleasure by triggering a surge of dopamine, the brain’s “feel-good” chemical, also linked to drug addiction.

This is why eating one biscuit often leads to finishing the whole packet: your brain is chasing the reward.

By contrast, foods like raw carrots do not cause the same dopamine spike. While nutritious, they do not intensely activate the brain’s reward system, so you stop eating when you are no longer hungry.

Junk food has the opposite effect, and children are particularly susceptible.

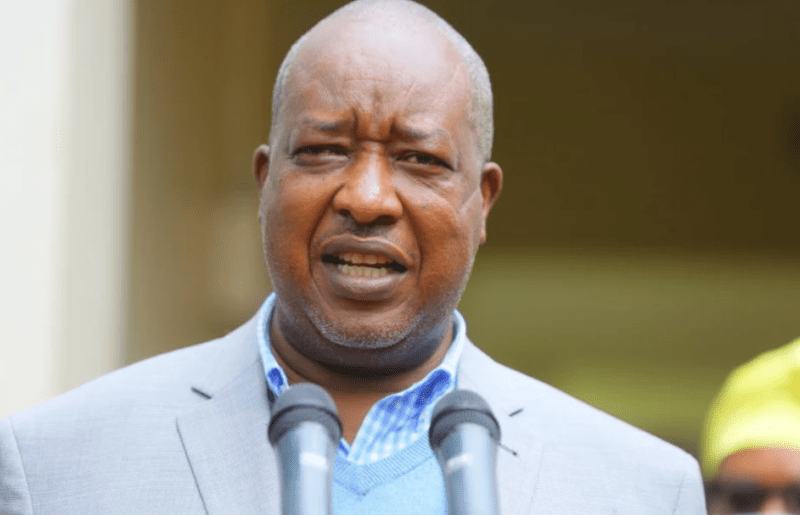

“Children’s brains are especially vulnerable because they are developing,” explains Dr Seline Wanjiku, a paediatric nutritionist in Nairobi.

“They have a developing reward system, and when it gets overloaded by these foods, it sets up a pattern of habitual eating. You give your child that once, and the cycle will never stop, because they are not eating for hunger, but for emotional satisfaction.”

The Nature Medicine article notes ongoing lawsuits in the US against companies accused of deliberately designing and marketing addictive snacks to children.

In 2024, US Congressional hearings even debated whether food addiction should be regulated like tobacco addiction.

Not just a habit—A public health crisis

The authors point out that neither the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) nor the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) formally recognises ultra-processed food addiction—an omission they call dangerous.

Dr Volkow, who has studied addiction for decades, says the same brain regions activated by cocaine or alcohol are also triggered when a child eats a hyper-palatable snack. This can lead to compulsive overeating and withdrawal-like symptoms when such foods are unavailable.

“This is not about willpower, it is not a person’s fault they can’t stop eating junk, it’s biology,” says Dr Volkow. “And children, who are in critical stages of brain development, are the most at risk.”

A 2021 meta-analysis found that around 14 per cent of adults and 12 per cent of children globally meet the criteria for ultra-processed food addiction—a rate similar to alcohol use disorder.

Researchers warn that children are prime targets for junk food marketing because they respond emotionally to adverts and can influence household buying decisions.

“Children aren’t the ones dealing with diabetes, high blood pressure, or dental problems—so from that perspective, many parents simply want to see their kids happy, especially when a treat brings a smile,” Dr Wanjiku says.

What parents can do: Five practical steps

1. Replace, don’t ban

Avoid outright bans, which can backfire. Instead, offer appealing alternatives like frozen banana slices dipped in dark chocolate, homemade popcorn with cinnamon, or natural yoghurt with fresh fruit.

2. Have set snack times

Stick to regular mealtimes with two planned snack breaks. Children snack more when meal schedules are irregular.

3. Limit screen time

Reducing screen time limits exposure to junk food marketing. WHO advises no more than one hour per day for children under five.

4. Change your own diet

Keep highly processed snacks out of the house and model healthy eating—children copy adult behaviour.

“If you want your child to choose water, they have to see you choosing it too,” says Dr Wanjiku.

5. Lead by example

Choose fruits, vegetables, and water over processed snacks and sodas to set a visible standard for your child.

A call for global action

In response to growing evidence, the US FDA and NIH have announced a joint initiative—modelled on the Tobacco Regulatory Science Program—to address food-related addiction.

In Kenya, similar advocacy is gaining momentum.

“There needs to be a global shift in how we think about food marketing to children,” says Dr Wanjiku. “We regulate cigarettes and alcohol—why not snacks that are just as addictive to a growing brain?”

Junk food is no longer just “junk”—it is a carefully engineered product with profound effects on children’s physical and mental health. The scientific consensus is clear: ultra-processed food addiction is real, and early intervention is essential.

“This is no longer just a dietary concern,” says the Nature Medicine team. “It’s a public health emergency.”

Top Stories Today