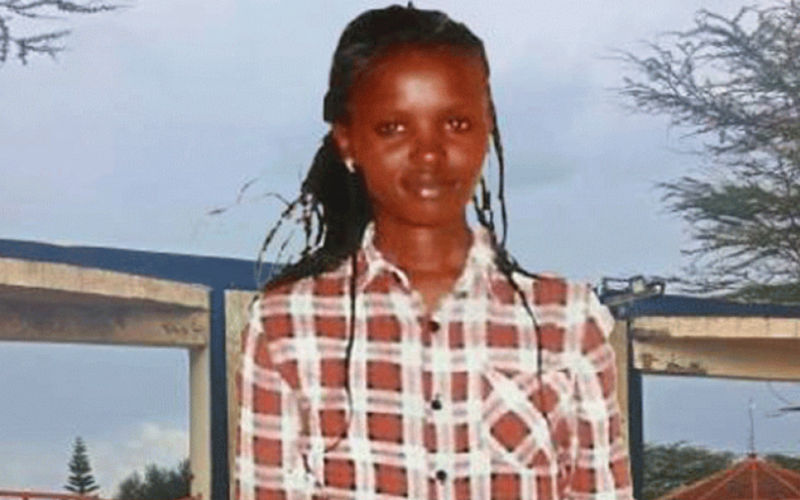

From Kariokor Market stall to global artistry: Nairobi beader Elizabeth Kioko’s inspiring journey

From this humble dish, she crafts pieces that travel far beyond her reach, to Rwanda, Tanzania, Cameroon, and West Africa — a testament to hands that refuse to give up, even when the world outside is uncertain.

On a typical Thursday morning, as the early Nairobi sun filters through the bustling Kariokor Market, Elizabeth Kioko sits quietly behind her roadside stall, her fingers expertly threading a delicate row of beads.

The distant sound of matatus heading into town mixes with traders’ laughter and the low hum of vendors bargaining for space and survival.

More To Read

- From waste to water tanks: How Kariokor youth are turning Nairobi’s trash into livelihoods

- Kalembe Ndile and the Kariokor tyre men: A story of survival, skill and silent impact

- Thread by thread: Kariokor’s women weavers stitch culture, resilience, and hope into every bag

- Forging the future: How Kelvin Kimuyu is reviving brass craft in Nairobi’s Kariokor Market

- Pastoralist women beading their way out of poverty and marginalisation

Within her small, open stall — marked only by wooden poles and nails from which her beaded designs hang — Kioko is creating beauty.

The space is barely a metre and a half wide. In front of her rests a worn, faded blue plastic plate, holding hundreds of tiny, colourful beads.

From this humble plate, she crafts pieces that travel far beyond her reach, to Rwanda, Tanzania, Cameroon, and West Africa — a testament to hands that refuse to give up, even when the world outside is uncertain.

A beaded sisal basket on display at Kariokor Market, perfect for storing jewellery and other small items. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

A beaded sisal basket on display at Kariokor Market, perfect for storing jewellery and other small items. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

“I wake up and make something, whether customers are there or not,” she says with soft, unwavering conviction. “Some days I sell nothing. But I don’t stop. At the end of the day, I believe my hard work will speak for me, maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but one day… it will pay off. That I believe is why I wake up every morning and do what I do.”

At 42, Kioko has spent the last 10 years turning thread and glass beads into art. She began as a quiet observer, watching women around her confidently weave necklaces with fluid hands.

At first, it took her a whole day to make three pieces; now she can complete a full necklace in under 20 minutes.

Beyond the necklaces

Her stall, though small, is vibrant, layered with shimmering pieces that tell stories waiting to be worn. Necklaces, beaded earrings, key holders, sandals, rings, waist beads, and even baskets designed to hold remotes or toilet paper fill the space. Some baskets hang like art on the walls; others rest in colourful piles, practical yet beautiful.

“Can I tell you something? These beads have travelled more than I have,” she laughs, eyes sparkling. “I’ve never even been beyond Kenya, not even to Mombasa, which is just kilometres away. Some pieces I’ve worked on are in Rwanda, Cameroon, West Africa… Europe — I send them all over the world, especially if I get consistent customers.”

Necklaces are displayed at Elizabeth Kioko's stall in Kariokor Market. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

Necklaces are displayed at Elizabeth Kioko's stall in Kariokor Market. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

It brings her joy knowing that while borders may limit her physically, her work knows no boundaries.

“There was this one mzungu (white man), I think from Germany,” she says, chuckling as she picks up a beaded wristband. “She came with a guide, spent almost 40 minutes here, kept touching everything, asking what it meant. She left with a full bag — necklaces, earrings, even two carvings. That day, I made Sh8,000. Just like that.”

She glances across the road as a group of tourists pass by.

“Now they don’t come much. Maybe they go to malls, or maybe the economy is bad, or they worry about security. But I remember the laughter, the excitement when they found something new. It gave us pride. We felt seen, as beaders — something you don’t see often here because business is slow nowadays.”

“This is not a side hustle” — My bread is here

Kioko is clear: this is not just a side hustle. It is her job, her passion, and how she feeds her family.

“It’s what keeps me going every day. If beadwork could speak, my beads would say I am patient, focused, and care about detail. Age is just a number; I started beading at 32, and here I am.”

When people dismiss roadside work as informal or unskilled, she straightens slightly, her hands never stopping.

“It’s not just threading beads. You have to be creative, watch trends, change patterns, colours, and styles. You learn to manage your money, your time, and your mistakes. This job teaches you things school never did, you know?”

On a good day, after decent sales, the first thing she buys is more beads and accessories.

“Reinvestment is key,” she says, though her smile fades. “But those good days are rare now. Sometimes, if I can’t afford new beads, I just change the design and use what I have differently.”

Though small, Elizabeth Kioko's stall in Kariokor Market is vibrant, layered with shimmering pieces that tell stories waiting to be worn. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

Though small, Elizabeth Kioko's stall in Kariokor Market is vibrant, layered with shimmering pieces that tell stories waiting to be worn. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

‘Uhuru’ bag

She pulls out a familiar blue ‘Uhuru’ bag from under her table. Inside are freshly bought beads — black, white, and gold — and a coil of black rope.

“I just got these from the shop up there,” she says, nodding toward the street above the stalls. “That’s where I source my beads locally. My work is to turn them into gems that customers will be proud to wear and show to others.”

As we talk, her hands never stop moving. She threads waist beads with practised ease, calm but focused. By the end of our conversation, she had already made ten beautifully unique waist beads.

“I want to try something new with these,” she adds, holding up the rope from the Uhuru bag. “A new design I’ve been thinking about — let’s see how it goes.”

From carvings to beads: A journey of self-taught artistry

Before discovering beadwork, Ms. Kioko bought and resold traditional carvings and paintings of rhinos, elephants, and giraffes, carefully crafted by local artists.

“Tourists and some Kenyans are mostly drawn to these pieces, especially for hotels or souvenirs,” she says.

Driven by curiosity and determination, she taught herself to make beads. Now, she sells her own bead creations alongside the carved animals and colourful paintings that still attract market visitors.

A shifting economy, a stagnant morning

“At this same time during Uhuru’s tenure, almost six years ago,” she recalls with a small sigh, “I would have sold Sh5,000 by now. But today…” she gestures to her nearly empty sales tin, “I have just Sh100, and it’s already 11 am.”

Yet she remains at her stall, with no other choice but hope that things will improve. If they don’t, tomorrow is another day.

Her children, who learned the skill by watching her, help when she gets large orders.

“There was this one time I had a client who ordered 200 custom necklaces,” she says. “I couldn’t believe it. The client was Cameroonian. I started working on them that same night.”

“I have hope. Maybe today I sell nothing, but tomorrow? Who knows. God provides.”

Community in the chaos

Around her, similar stalls ripple with beadwork in all shapes, sizes, and colours. But these aren’t cutthroat competitors.

In Kariokor market, community matters.

“We live like a family here. Sometimes it’s hard — the chief’s office is far, so reporting a case can be tricky. If something happens, we sort it among ourselves. We watch each other’s backs.”

When asked who she turns to in hard times, her answer is simple:

“The woman next to me.”

There’s an unspoken sisterhood — a shared understanding of slow days, delayed clients, rising costs, and the quiet pride in a well-finished piece.

“Only fellow beaders understand the pain of finishing a complicated design, only for someone to ask if they can buy it for Sh.100,” she says with a tired smile. “That’s why some designs range from Sh500 to even Sh3,500.”

More than just beads

Just up the street from her stall are shops filled with beads of all sizes and colours, sourced locally and abroad — fine glass, wood, and imported finishes.

Prices vary widely, from as low as Sh50 to intricate pieces fetching Sh2,000 or more.

Next to her, a rare man in these circles, Samson Nthenge, carefully aligns a wristband pattern.

“He’s been here for years, too,” Kioko notes with a smile. “Not many men do this, but the few who do are very talented. He makes key holders, hair clips, necklaces, and wristbands.”

Before leaving, I buy two waist beads for Sh100 and a unique, beautifully beaded leather hair clip. It may not change her day’s earnings, but her smile shows it matters as she carefully fits the clip around my waist.

Between artists and authorities

The work here is real. Walking through the market, I feel the beads, wear the necklaces, and admire the craftsmanship. People of all ages — from 19 to 60 — dedicate themselves to the craft and sell despite low earnings, appreciating being part of this community.

But beneath the friendly smiles lie frustrations.

“Yes, city officials come asking for money almost every day. I have to set aside Sh50 for them, even when I make no sales,” she says, frustration creeping into her calm voice.

“We pay for permits, yes, but we pay every day. Otherwise, all your hard work can be taken away. But who listens to us?”

What she wants is simple: for someone, especially the Starehe area MP, to see them, support them, and give them a platform.

“Even if it’s just setting up pop-up markets or finding markets abroad so we can export our art, that’s enough for us. We just need help reaching them.”

Legacy in loops

For Kioko, beadwork is not just a job — it is becoming a legacy.

Her children, exposed to the craft from an early age, have begun learning the skill — not by force, but out of admiration.

“I feel empowered watching them. Most young people want quick money or office jobs nowadays. But this? This is steady. This is real. It’s a skill they’ve learned and maybe one day will teach their children. But I don’t force them. I want them to do what they love and focus on their education — that’s why I am here, to provide for them.”

If her work were passed down like an heirloom, what would it carry?

“Strength,” she says simply. “My work is about persistence. Even in the darkest days, I choose to see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

If Kariokor market were torn down tomorrow, what would she carry with her?

“My tools. My thread. My beads. That’s all I need to start again. My work isn’t on social media yet, but it’s in people’s hands, in their homes, and that’s enough for now.”

You could take away the stall, the tourists, the orders, even the money.

But not the hands, not the art, and not the hope.

Top Stories Today