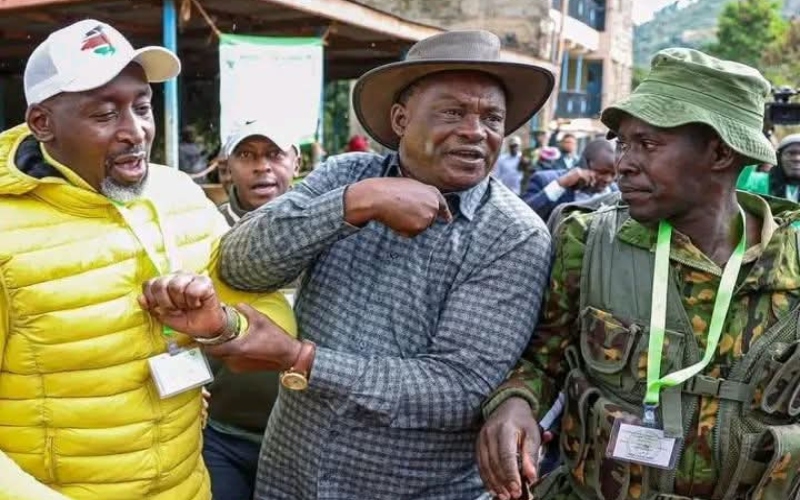

Nearly 43 per cent of Kenyans report police abuse, study shows

The Justice System Response to Police Accountability report by International Justice Mission Kenya engaged 5,700 participants across nine counties through surveys and 17 focus group discussions, revealing a persistent culture of abuse, mistrust, and weak accountability within the country’s criminal justice system.

A nationwide study shows police abuse of power remains widespread in Kenya, with nearly 43 per cent of citizens reporting personal experiences of misconduct between March 2022 and March 2024.

The Justice System Response to Police Accountability report by International Justice Mission Kenya engaged 5,700 participants across nine counties through surveys and 17 focus group discussions, revealing a persistent culture of abuse, mistrust, and weak accountability within the country’s criminal justice system.

More To Read

- Kanja admits police could have done better in handling Gen Z protests, advocates for training

- Man held in Kilimani over Sh2.5 million police recruitment scheme

- IPOA decries low turnout in police recruitment, recommends two-day exercise

- Gen Z protests in Kenya: Key facts (2024-2025)

- Amnesty report shows at least 128 killed, 3,000 arrested in 2024–2025 Gen Z protests

- IPOA launches nationwide monitoring of police recruitment to ensure fairness, transparency

While the prevalence of personal victimisation has slightly decreased from 46.2 per cent in 2019 to 42.9 per cent, the scale of misconduct remains concerning.

An even higher proportion, 69.9 per cent, reported witnessing police wrongdoing, indicating that abuse is highly visible in everyday life.

The study grouped misconduct into three categories: low, medium, and high severity. Medium-severity abuses were most common, accounting for 85.2 per cent of reported cases, with corruption or extortion (55.8 per cent) and harassment (54.7 per cent) leading.

Low-severity misconduct, including verbal intimidation, made up 31.3 per cent, while high-severity incidents causing serious harm or rights violations accounted for 27.7 per cent.

Men were more likely to experience abuse than women, at 61.4 per cent versus 38.5 per cent, and urban residents bore the brunt compared to rural communities (75.9 per cent versus 24.1 per cent).

Higher education also appeared to increase exposure, with 67.7 per cent of victims having a tertiary education.

Regionally, Kisumu County recorded the highest rates of misconduct across all severity levels.

The 25–34 age group was most affected, especially by high-severity abuses, which stood at 24.4 per cent.

Focus group discussions further revealed that certain groups were particularly vulnerable, including youths, informal workers like matatu touts and hawkers, Muslims and Cushitic communities, sex workers, and people with visible traits such as long beards, tattoos, or dreadlocks.

Despite high victimisation, many Kenyans expressed readiness to seek justice: 63.7 per cent said they would report misconduct, and 88 per cent said they would participate in legal proceedings.

Yet among the 2,444 individuals who experienced abuse, 62.6 per cent did not report their cases.

Of the 915 reports made, just over half (52.5 per cent) reached criminal justice agencies such as the Independent Policing Oversight Authority, Directorate of Criminal Investigations, or Internal Affairs Unit, while 45.6 per cent were lodged with chiefs or community leaders.

Encouragingly, 75.4 per cent of survivors who entered the justice process remained engaged, though nearly a quarter (23.6 per cent) withdrew midway.

Focus groups identified several barriers to justice. Lack of trust in institutions was the most cited reason, with many seeing police, courts, and oversight bodies as corrupt or ineffective. Financial constraints, including high legal fees, transport costs, and prolonged court proceedings, also discouraged reporting.

Fear of retaliation was a major concern, particularly in regions with prevalent police abuse, with victims worried about harassment, intimidation, or physical harm.

The absence of a robust witness protection system left many exposed, while institutional inefficiencies, including slow investigations and poor coordination by IPOA and the IAU, further delayed justice.

The study paints a stark reality: while Kenyans are willing to engage with the justice system, systemic obstacles force many to endure abuse in silence, perpetuating a cycle of impunity and mistrust.

Top Stories Today