Violence in South Sudan is rising again: What’s different this time, and how to avoid civil war

This conflict can be traced back to historical tensions between the Nuer and Dinka communities, worsened by the 1991 split of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), a political party.

A rise in political tensions in South Sudan and an escalation of violence in the Upper Nile State have raised fears of a return to civil war in the world’s youngest nation. In early March 2025, neighbouring Uganda sent troops to South Sudan at the request of the government, and they were involved in aerial bombardments.

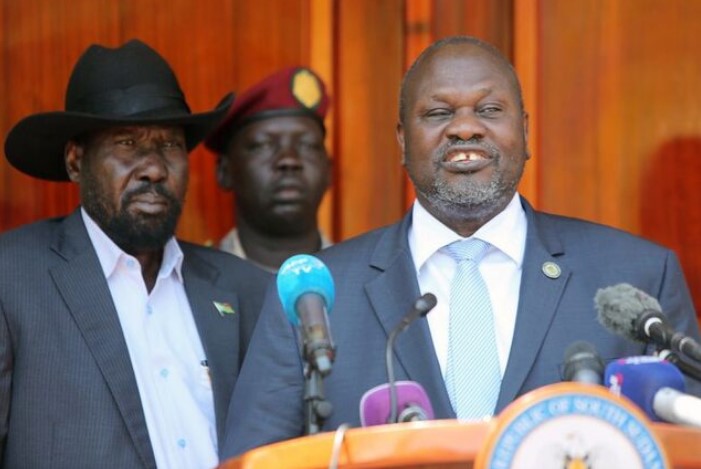

South Sudan’s opposition groups took issue with the Ugandan intervention, and stopped taking part in discussions to create a joint military system in the country. These developments risk unravelling the 2018 power-sharing deal between President Salva Kiir, and First Vice-President Riek Machar and other opposition leaders. This deal brought a halt to a five-year civil war. Jan Pospisil, who has researched South Sudan’s political transition, unpacks the drivers of growing discontent.

More To Read

- Attack on MSF hospital in South Sudan was deliberate, UN rights commission says

- Bombing destroys last functional health facility in Jonglei State, South Sudan

- UN extends South Sudan peacekeeping mission by nine days amid escalating tensions

- South Sudan peace deal under threat as key opposition leaders detained

- South Sudan's military recaptures key town from White Army militia

- South Sudan dispatches high-level delegation to US for urgent deportation and bilateral talks

What’s the current situation in South Sudan?

In early March 2025, the White Army, a Nuer community militia, launched attacks against units of the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces in Nasir County, Upper Nile State.

This sparked fierce fighting. Nearly 50 people have been killed so far and many more wounded. The White Army claims it acted in self-defence. The militia group defends the Nuer community, one of the country’s major ethnolinguistic groups.

This outbreak of violence follows patterns of conflict from 2024 and years before. But it has spiralled out of control. The government’s response – including aerial bombardments with the support of the Ugandan army and arrests of leading opposition figures – has inflamed tensions.

This conflict can be traced back to historical tensions between the Nuer and Dinka communities, worsened by the 1991 split of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), a political party.

After the split, Riek Machar established a Nuer-dominated faction called SPLM-Nasir. It broke away from the John Garang-led SPLM, which was said to be Dinka-dominated. The split led to years of infighting.

The White Army itself emerged during this period in the 1990s. It was primarily concerned with Nuer community defence and cattle raiding. It has never been controlled by any political entity.

Machar has tried but never succeeded to command all Nuer militias, including the White Army.

The White Army’s independence remains crucial in understanding the current situation in South Sudan. Many statements – often deliberately to discredit the opposition – conflate White Army actions with South Sudan’s opposition strategy. Such statements downplay the existing grievances in Nasir County.

What’s different this time compared to the outbreak of civil war in 2013?

When South Sudan’s civil war erupted in 2013, Nasir was engulfed in violence. Government troops—largely of Dinka origin— perceived the Nuer-majority town as enemy territory. Their attacks were often an attempt to take revenge for the atrocities committed by the White Army against Dinka civilians in the 1990s. Nuer fighters retaliated in kind. This trapped civilians in cycles of violence. By August 2014, Nasir had become desolate, with its infrastructure reduced to ashes.

The White Army’s recent attacks appear to be motivated by a series of provocations rather than any centralised political directive.

Clashes erupted in mid-February 2025 when White Army members attacked soldiers collecting firewood. Four soldiers died, and at least 10 civilians were injured by retaliatory shelling from the army.

Other Topics To Read

This incident heightened animosities, resulting in violent attacks. In March 2025, army forces suffered a humiliating defeat. This embarrassed the government ; it looked like the national army was unable to control a community militia. This provoked a crackdown, and the White Army pushed back.

The White Army seized Nasir and parts of the Wec Yar Adiu army barracks on 4 March.

A planned evacuation of army troops via a UN peacekeeping helicopter on 7 March was disrupted when an exchange of fire led to casualties. At least 27 soldiers died, including Nasir army commander Majur Dak, a Dinka from neighbouring Jonglei State, and a UN peacekeeping crew member.

In response, the SPLM-led government has moved to scapegoat the opposition.

Several opposition figures, including oil minister Puot Kang Chol and opposition chief of staff Gabriel Duop Lam, were arrested.

The government’s narrative suggests that the opposition orchestrated the White Army attacks as part of a broader destabilisation effort in the country.

However, this ignores the fact that the White Army has historically acted independently. The arrests appear to be an opportunistic move to weaken the opposition, rather than a genuine attempt to address the root causes of the violence.

What can be done to avoid a return to war?

The path to stability lies in dialogue and sustained community demobilisation.

The government needs to refrain from randomly arresting opposition figures because it feels humiliated. And it needs to stop indiscriminate attacks against civilians, such as aerial bombardments, in Nasir County.

At the same time, community leaders, particularly those with influence over White Army factions, should be engaged in negotiations to de-escalate the situation.

The coming rainy season, expected to start in April, provides a natural window for such efforts. Logistical challenges will make large-scale armed operations more difficult. This period could allow for confidence-building measures on the ground between Nuer communities and the army.

And internationally?

The international community has responded to the unfolding crisis with condemnations of the violence in Nasir. However, there has been little action.

The UN mission in South Sudan has called for restraint from all sides but has largely failed to acknowledge the complex, independent nature of White Army mobilisation. The head of the UN mission should clearly call out the arrests of opposition figures as unbased and a threat to the transition process.

The lack of such statements risks reinforcing government narratives that justify the use of heavy military force. The UN and international actors must emphasise the need for de-escalation, while also advocating for political solutions that address underlying grievances.

Top Stories Today