Is Kenya ready for next health crisis? Unpaid workers, weak systems raise alarms after Covid

Without adequate investment in human resources and infrastructure, Kenya may struggle to respond effectively to future health emergencies, thereby compromising its ability to protect citizens in times of crisis.

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, the world was forced to adapt to new realities as an unknown disease swept across nations, leaving families devastated by loss and widespread job insecurity.

Many have yet to fully recover from the disruptions it caused. With uncertainty surrounding how to handle the situation, society clung to basic measures like sanitising, wearing face masks, and maintaining a 1.5-meter distance.

More To Read

- Kenya's clinical officers call off nationwide strike after sealing deal with government

- Clinical officers’ union boss claims cartels in defunct NHIF now sabotaging SHA implementation

- Clinical officers announce nationwide strike over unresolved issues

- Lamu, Kwale among counties where clinical officers’ strike continues despite 21-day suspension

- Clinical officers accuse government of discrimination, unfulfilled promises as strike begins

- Hospitals seek detailed breakdown of SHIF payments amid ongoing delays

This "new normal" became a way of life.

The pandemic severely strained healthcare systems, exposing systemic weaknesses and gaps. Healthcare workers, who were also facing the pandemic for the first time, bravely put their lives at risk to fight the virus.

In Kenya, significant strides were made in the response, including the administration of over 23.7 million vaccine doses, with 21.09 per cent of the population fully vaccinated and 27.57 per cent partially vaccinated.

As of 2023, Kenya reported a total of 344,094 confirmed Covid-19 cases. The pandemic has claimed 5,689 lives, while 337,225 individuals have successfully recovered.

However, despite these efforts, the lingering effects of Covid-19, such as Long Covid, continue to strain the healthcare system.

Deep cracks

Long Covid reveals deeper cracks that the initial response never fully addressed, with an estimated six out of every 100 people who were infected living with persistent symptoms like fatigue, brain fog and respiratory issues, conditions that many public hospitals are ill-equipped to handle, according to the World Health Organisation.

Amid these challenges, one of the most significant issues is the treatment of healthcare workers who risked their lives during the crisis.

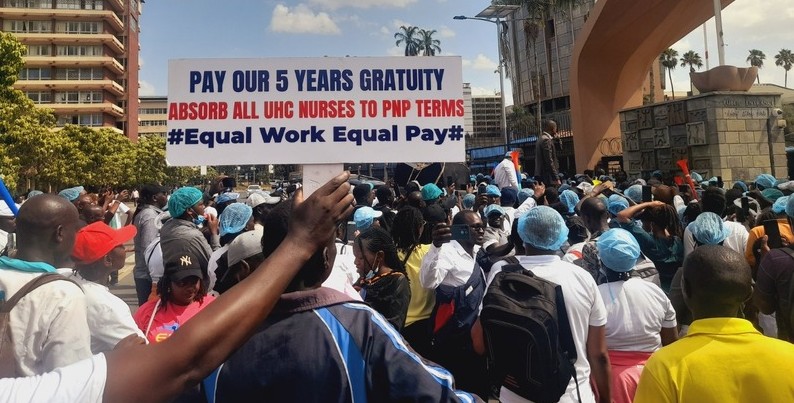

Despite their immense contribution, many frontline workers and members of task forces still await unpaid gratuities five years later. This reflects the broader issue of the undervaluation of Kenya’s healthcare workers, whose efforts were instrumental in managing the pandemic.

As the country grapples with the long-lasting effects of the previous crisis, the critical question arises: Can Kenya manage another health crisis when it has yet to recover from the last one?

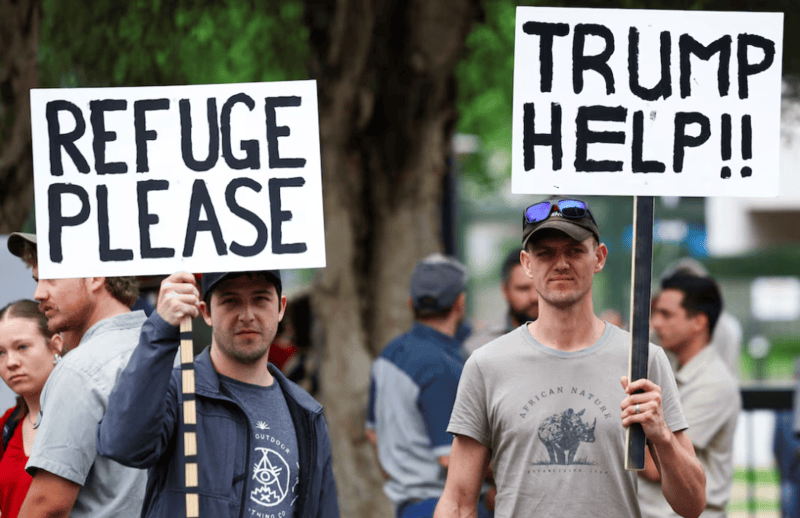

Many UHC workers, including over 8,500 employed during the Covid-19 period, have turned to social media and protests to express their frustrations. Currently, these workers are deployed across all 47 counties under the Ministry of Health, earning only 50 per cent of their salary while still being subjected to full civil deductions for the last five years. Despite their significant role in supporting the country during the pandemic, these workers feel neglected

Many of these frontline workers are paid a stipend, only a fraction of what they should be earning compared to their counterparts. Leaders have raised concerns over the issue.

Despite their invaluable contributions, they have faced unfulfilled promises. This brings up a crucial question: if another pandemic strikes, will health workers still be willing to risk their lives? What will be the consequences if their efforts continue to be undervalued and overlooked?

Matter unsettled

Peterson Wachira, the chairperson of the Kenya Union of Clinical Officers, stated that "This matter, therefore, remains unsettled and requires further deliberations and an all-inclusive agreement with the relevant unions."

He said UHC staff have endured unfavourable terms for the past five years.

"It is time to end the discrimination as a matter of urgency and in appreciation of their indispensable services to our nation," he said.

Kenya’s healthcare system, while making progress, continues to face significant gaps that hinder its ability to provide comprehensive and equitable care. These weaknesses were exacerbated by the pandemic and remain unresolved, leaving the healthcare system vulnerable.

One major gap is unequal access to healthcare services.

A stark rural-urban divide persists, where urban areas benefit from better-equipped hospitals and a higher concentration of healthcare professionals, while rural areas face shortages of medical staff and facilities.

In many remote areas, healthcare centres remain underfunded, leading to poor health outcomes. This disparity is especially pronounced in regions such as the north eastern parts of the country where poor infrastructure and insecurity further exacerbate access challenges.

Inadequate infrastructure

Another critical gap is inadequate healthcare infrastructure.

Many hospitals, especially in low-income areas, lack essential equipment, reliable electricity, and clean water, making it difficult for healthcare providers to deliver quality care.

Overcrowding in public hospitals, particularly in major cities like Nairobi, also poses a serious problem. With limited resources, long waiting times and poor-quality care have become the norm for many patients, further straining the system.

Shortages of healthcare workers are another persistent challenge.

Many skilled healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, leave Kenya for better opportunities abroad due to low pay and poor working conditions. Those who remain often face delayed salaries and unsafe working environments, contributing to dissatisfaction and strikes. This issue is compounded by Kenya’s underfunded healthcare system, where the public health budget is insufficient to meet growing demands.

Essential medicines and equipment remain in short supply, and while the private healthcare sector continues to expand, it remains out of reach for most Kenyans, particularly those in the informal sector.

Weak health systems governance also plays a significant role in the system's inefficiency.

Corruption and mismanagement of healthcare funds often divert critical resources away from where they are most needed. This misallocation hinders the ability of hospitals to provide adequate services, especially in rural and underserved areas.

Moreover, despite decentralisation efforts, the management of Kenya’s health systems remains inconsistent, with counties facing difficulties in delivering services equally across regions. This leads to uneven healthcare provision and persistent inequities in care.

Mental health

Mental health issues have long been neglected in the healthcare system, with few resources dedicated to addressing the growing need. There is a significant shortage of trained mental health professionals, and public awareness remains low. This gap in services leaves many Kenyans without the support they need to manage mental health conditions.

In addition, health insurance coverage remains inconsistent. Many Kenyans, particularly those in the informal sector, are unable to access affordable health insurance.

Vulnerable populations, including the elderly and people living in poverty, often face high out-of-pocket expenses for necessary treatments. This places a heavy burden on the already overstretched public healthcare system.

The weak disease surveillance and response systems in Kenya were starkly exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The country’s limited capacity to monitor and respond to health crises meant that it struggled to effectively manage the outbreak. Inconsistent health data collection, lack of digital infrastructure, and poor coordination among health agencies hindered timely and effective decision-making.

The fragile health supply chain continues to present a significant challenge.

Shortages of essential medicines and medical equipment, coupled with inefficiencies in the procurement system, result in unreliable access to critical resources, undermining the quality of care across the country.

UHC staff payroll

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale has proposed transferring the management of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) staff payroll to county governments, starting on July 1, 2025. This proposal has generated mixed reactions among UHC staff, who are concerned about job security, gratuity and the permanent terms of service they were promised when they were hired to help manage the pandemic.

Experts have raised serious questions about the country's preparedness, particularly given the ongoing strikes by frustrated health workers over unfulfilled promises and unresolved collective bargaining agreements.

While Kenya made significant strides in its response to Covid-19, numerous gaps remain in its healthcare system, which require urgent attention.

Healthcare workers, especially those in task forces, played a critical role in managing the pandemic. However, the persistent failure to properly compensate and support these workers puts the country at risk.

Without adequate investment in human resources and infrastructure, Kenya may struggle to respond effectively to future health emergencies, thereby compromising its ability to protect citizens in times of crisis.

Top Stories Today