G20 and the civil society elite: Spectacle instead of meaningful action

The G20 was formed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when the collapse of major banks and housing markets exposed deep cracks in the global economy.

Luke Sinwell, University of Johannesburg

More To Read

- Africa’s food security challenge: G20 calls for boost in trade and sustainable farming solutions

- What will it take to make Africa food secure? G20 group points to trade, resilient supply chains and sustainable farming

- Surviving the next pandemic could depend on where you live

- President Ruto urges global unity to fight poverty, inequality at Doha summit

- Climate crisis is a daily reality for many African communities: How to try and protect them

- African countries gear up for major push on climate innovation, climate financing and climate change laws

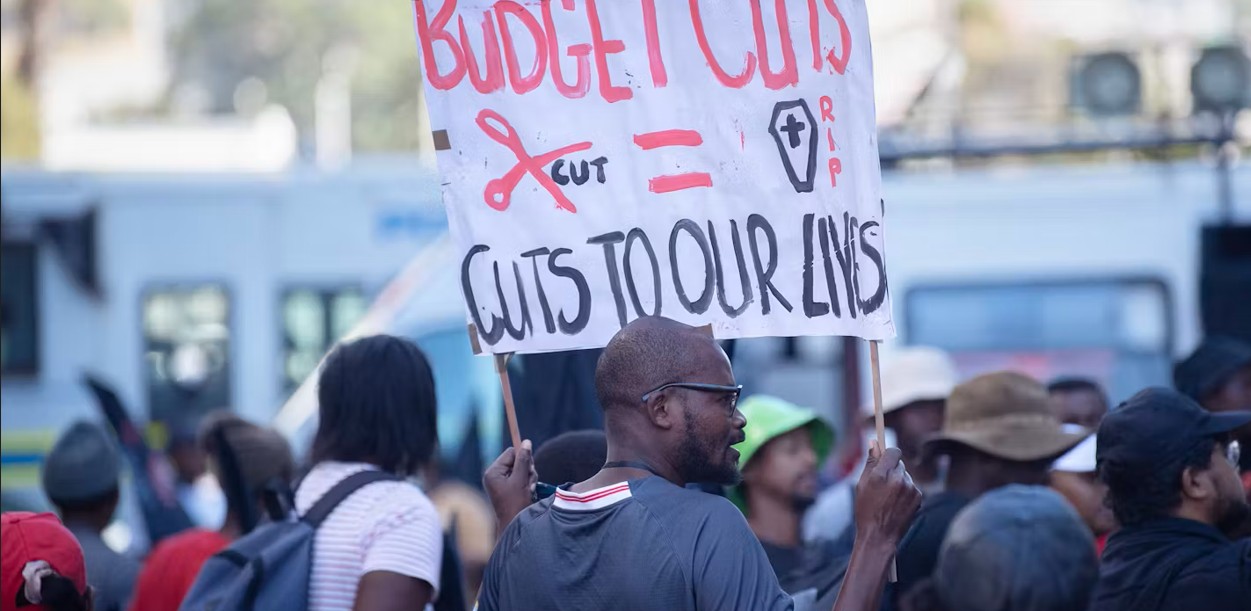

Behind the talk of fighting inequality at the group of 20 most powerful economies in the world, the G20, lies a carefully staged show – one that manages dissent rather than redistributes power.

Inequality is at the top of the G20 agenda this year, with South Africa holding the presidency. President Cyril Ramaphosa has said that if the G20 wants to tackle major global economic challenges, it must act fast to reduce inequality.

Well-funded non-governmental organisations like Oxfam have praised this stance, saying that the G20 is: giving a voice to people crushed by inequality. They are showing that another world is possible: ruled not by and for billionaires, but by and for the rest of us instead.

But such organisations don’t directly represent grassroots constituencies. In commenting on inequality, they risk making blanket statements which do not reflect the local reality and politics of ordinary people on the ground.

South Africa is still the most unequal country in the world. My research on grassroots democracy in townships and informal settlements shows that most residents have been silenced in the name of democracy. The ANC government’s market-based policies turned basic needs like water and electricity into commodities and reinforced the private property system inherited from apartheid.

Economic inequality has deepened in the post-apartheid era, since 1994. As a result, one of South Africa’s union federations objected to the South African government even talking about inequality because of the government’s role in creating it.

As a sociologist who researches protest and civic responses to inequality, I have found that participation, when stripped of confrontation, becomes a technology of legitimacy. In other words, including grassroots communities in discussions about governance, public services, and other social and economic issues becomes a polite consultation.

This justifies existing power structures instead of challenging them. People may appear to have a voice, but the outcomes are already decided.

I argue that the G20’s inequality agenda is simply a way of governing through spectacle or political theatre – a show in which leaders can appear to respond to serious problems faced by the working class while protecting the system that benefits elites.

My own research points not only to the exclusive nature of forums similar to the G20, but also suggests that these forums can be genuinely transformed through disruptive acts or protests led by democratic grassroots organisations with a socialist vision.

The G20’s claims of partnership with civil society

The G20 was formed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when the collapse of major banks and housing markets exposed deep cracks in the global economy.

The G20 was created to restore confidence and show that leaders were listening to ordinary people. It presented itself as a forum of inclusive global governance, where the world’s major economies come together to “listen” to civil society and address crises collaboratively.

As part of the G20’s process of consulting different sectors of society ahead of its annual summits, elites (such as heads of state and finance ministers) hold joint press conferences with non-profit organisations and dialogues with civil society.

Working groups of activists and elites are formed, and consensus statements are issued. But there’s no handover of power or action taken to dismantle capitalism, which keeps poverty and inequality in place.

In other words, minor but important reforms can potentially be made to the benefit of the working class, such as minimum wage laws and universal health care – which we should support – but the underlying process of development – based on a capitalist mode of production – relies on the extraction of resources, the destruction of the environment and exploitation of those with the least.

How the G20 uses public participation as a performance

My book, The Participation Paradox, offers a lens through which the G20’s current performance of “participation” can be viewed.

In the book, I argue that governments and international institutions now routinely invite communities into participatory forums. But these gestures often depoliticise struggle. In other words, they appear to be a space where the powerful include working-class and impoverished communities, allowing them to have a say. However, these forums often reproduce top-down power. They do this by setting the agenda, controlling who gets to speak, and limiting what can actually change.

In this way, participation becomes less about empowering ordinary people to take part in important decisions about public spending, governance, service delivery and other pressing issues and more about legitimating decisions already made.

This is done through a performative “listening” designed to stabilise, not subvert, the capitalist order. In other words, it is mostly for show. The G20 reaffirms the system of capitalism, which reproduces inequality and puts profit before people.

In this sense, the process works as a spectacle – a public performance where those in power put on a show of listening and action to make things look democratic, even though very little actually changes.

I’ve also done research in Thembelihle, an informal settlement in Johannesburg, South Africa. I found that public consultations gave the appearance that the government was including communities in decision-making. However, there were no changes to structural inequalities – the system of capitalism and private property. These were left undisturbed. What appeared democratic was, in fact, a way to manage people’s discontent.

Where opposition emerges: the Civil 20

The Civil 20 (C20), an official civil society engagement group for the G20, seems to offer an alternative. It is made up of representatives of over 3,000 organisations worldwide. Its objective is to hold the G20 to account. But does it have any real power?

The C20 2025 Declaration states: The path ahead must be grounded in participation, redistribution, and environmental justice … Let this be the year civil society was not simply heard, but heeded.

Being heard, however, is not the same as wielding authority. As the G20 summit unfolds, we are likely to witness the C20 being used as window dressing.

My research has found that real action is more than the facade of participation and spectacle. It requires a different vision, a socialist project which puts people’s needs before the greed of “bosses”.

The Conversation

***

Luke Sinwell, Professor of Sociology, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Top Stories Today