How critical minerals contribute to instability in Africa

The race to mine critical minerals has fed instability across Africa, whether displacing residents to increase extraction or upping the stakes in armed conflicts. DW looks at where minerals are mined and at what cost.

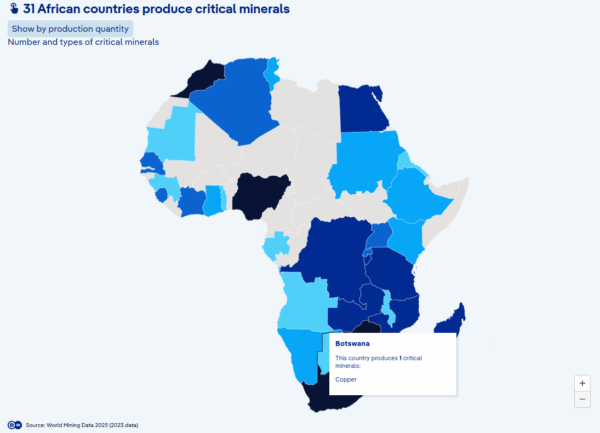

Coveted for their use in environmentally oriented infrastructure and other emerging technologies, critical minerals are mined in 31 of the 54 countries on the African continent.

South Africa, Nigeria and Morocco mine the largest variety of minerals — Guinea is the leader in terms of metric tons of minerals mined.

More To Read

- Explainer: What we know about coup allegations rocking Mali’s military

- Are African countries aware of their own mineral wealth? Ghana, Rwanda offer two different answers

- Mist and metal: Coltan grab in eastern DR Congo

- Guinea-Bissau’s political crisis: a nation on the brink of authoritarianism

- DR Congo President Tshisekedi meets US lawmaker amid talk of mineral deal

- Political instability threatens Africa's future – President Ruto

The world's race to extract critical minerals could prove highly profitable for countries across Africa. However, a lack of coherent labour and environmental standards, as well as little cross-border collaboration, has meant that, for now, critical minerals have been yet another source of uncertainty in many countries.

"If today we had a regional agreement on how to exploit the minerals, that could be a factor giving stability," said Jimmy Munguriek, a lawyer and the country director in the Democratic Republic of Congo for the NGO Resource Matters.

"On the other hand, minerals can also be the cause of political instability," Munguriek said.

31 African countries produce critical minerals. (DW)

31 African countries produce critical minerals. (DW)

'Exploitation and smuggling' of coltan in DRC

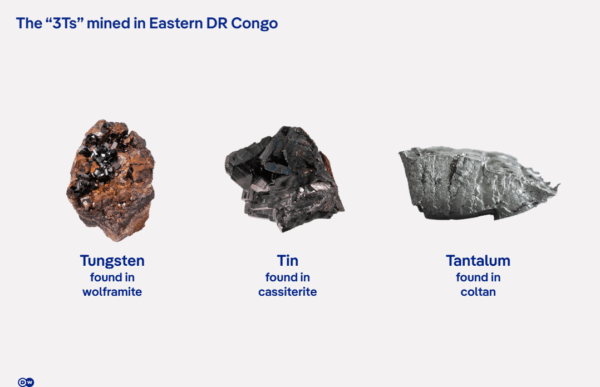

Disputes over who has the right to exploit the DRC's wealth of coltan, the critical mineral from which the highly conductive metal tantalum is derived, have contributed to three decades of unrest in the country's east.

Along with tin and tungsten, tantalum is one of the 3T metals increasingly sought to power consumer electronics, such as laptop computers and smartphones, medical devices and aerospace and defence applications.

The looting of the 3Ts has made the insurrection by the Congo River Alliance (AFC), a coalition of armed groups in the eastern DRC led by the M23 paramilitary group, increasingly lucrative for the militants. The fight to reclaim the mines and stop the smuggling has also upped the stakes for the DRC's government.

In April 2024, AFC forces seized control of the Rubaya mining site, which produces 20-30 per cent of the coltan used worldwide and is, therefore, essential to the global supply.

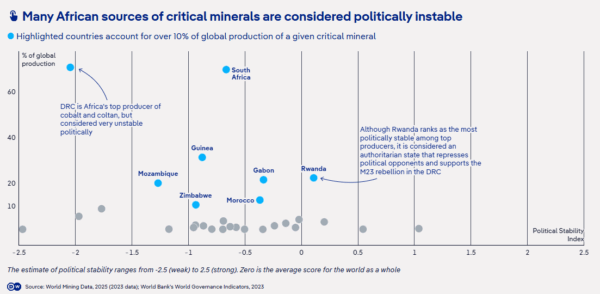

Many African sources of critical minerals are considered politically unstable. (DW)

Many African sources of critical minerals are considered politically unstable. (DW)

A parallel administration has been established by the AFC, which now controls the provincial capitals of Goma, North Kivu and Bukavu, South Kivu. In their report on the first half of 2025, UN researchers write that Erasto Bahati, the North Kivu governor appointed by the AFC, "was the key figure behind the illegal exploitation and smuggling” of minerals since the capture of Rubaya.

At least 150 metric tons (165 US tons) of coltan are extracted monthly from the mine and fraudulently exported.

The smuggling threatens the traceability of minerals through the International Tin Supply Chain Initiative (ITSCI), which is designed to ensure a "more responsible" supply of raw materials for industries, produced without the involvement of armed groups and child labour.

The United Nations warns that this practice represents "the largest contamination of mineral supply chains in the Great Lakes region recorded to date."

Investors turn away from the Sahel

Several countries where critical minerals are rarely mined are in the Sahel region, where military juntas have taken power in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, and insecurity is on the rise.

"In some countries in Africa, when there's been a change of regime, companies have seen laws changing unilaterally," Munguriek said. For businesses, this can mean an increase in taxes or a revision of their contracts with the state.

Cote d'Ivoire is emerging as a West African haven for gold-mining companies fleeing the Sahel's instability. In 2023, the country produced over 50 metric tons (55 US tons) of gold, and the government aims to double that output by 2030. If this effort is successful, Cote D'Ivoire could surpass its northern neighbours, Mali and Burkina Faso, where production has stagnated because of the instability that has followed the countries' respective coups in 2021 and 2022.

The “3Ts” mined in Eastern DR Congo. (DW)

The “3Ts” mined in Eastern DR Congo. (DW)

New initiatives for producing critical minerals

As buyers increasingly seek to avoid conflict zones, several mining initiatives for critical minerals are emerging across Cote d'Ivoire. Though the DRC and Rwanda continue to dominate global coltan production, Cote d'Ivoire, already a key exporter of manganese and bauxite, is positioning itself as a credible alternative in a market disrupted by the ongoing conflict in Central Africa.

In May, UK-based Switch Metals announced the launch of its coltan exploration programme on the Badinikro permit, part of the Issia project in central Cote d'Ivoire.

The country is also bringing its own enterprises into the sector, notably BRI Coltan, which is majority-owned by Firering Strategic Minerals and is developing a coltan-processing plant. The state-owned mining company, SODEMI, has partnered with a Chinese firm, Jiangxi Asia-Africa Xinghua Minerals, to develop a future coltan mine.

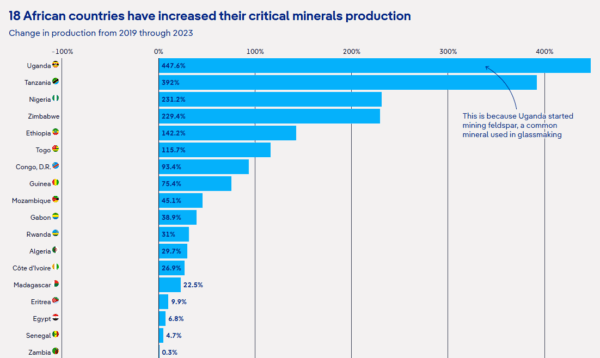

Beyond West Africa, Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa are also notably increasing their production of critical minerals such as feldspar, copper and manganese.

"For a country like Nigeria, a petroleum country, critical minerals could be an asset to steer Nigeria towards the energy transition — first for its own internal policies, but also for the global interests at stake today," Munguriek said.

18 African countries have increased their critical minerals production. (DW)

18 African countries have increased their critical minerals production. (DW)

Mining and displacement in DRC and beyond

The extraction of critical minerals is reshaping the population centres surrounding the operations in countries such as the DRC.

COMMUS, a joint venture between China's Zijin Mining and the DRC's state-owned Gecamines, is responsible for constructing a new district in the mineral-rich region around Kolwezi, in the country's south.

Sylvain Ilunga Muleka, a metallurgy technician and a leader of the efforts to relocate his community, said there had been a nearly decade-long delay in the construction of residents' future homes, about 30 kilometres (18 miles) away from their current site, known as the Gecamines neighbourhood, in Kolwezi. In 2017, the district was home to 39,000 people; after waves of relocations and evictions, about 2,000 residents remain, according to the Pulitzer Centre.

"The explosion coming from the mine shakes our walls," Muleka said. "It's really risky. We have to speed up the relocation process."

Top Stories Today