Waste, industrial effluent continue to choke Nairobi River despite clean-up efforts

Many dump their rubbish into open sewers that eventually flow into the Nairobi River, while others burn their waste or throw it directly into the river, exacerbating the environmental and health crises in the area.

The Nairobi River remains a distressing sight, its green-black water emitting a stench that lingers in the air. Floating debris, including gunny sacks, plastic carrier bags, and open sewage, drifts aimlessly on its surface, painting a grim picture of neglect.

Months after the launch of ambitious climate restoration efforts, the persistent contamination continues to defy clean-up initiatives.

More To Read

- Climate funding falling short for East Africa’s vulnerable communities, IGAD warns

- Millions of hectares are still being cut down every year. How can we protect global forests?

- COP30 delivers mixed results on climate action, WEF experts say

- Managing conflict between baboons and people: what’s worked - and what hasn’t

- Kenya, Sweden partner to curb billions lost in post-harvest food waste

- UNEA-7 opens in Nairobi as global environmental diplomacy faces major challenges

While some progress has been made, it has been painfully slow, leaving the vision of a revitalised river where people might one day consume fish feeling like a distant dream.

The dream of consuming fish from the river was floated by President William Ruto,

Richard Musila, a Nairobi resident, highlights the ongoing struggles faced by communities living near the Nairobi River. He observes that residents are often blamed for the pollution, a situation that has led to the demolition of homes built on riparian land.

“We’ve noticed that the clean-up efforts aren’t making much of a difference,” he says. “They only clean a stretch of about 100 metres, and it’s the same area being cleaned repeatedly. Meanwhile, where we are as Nairobi Handicraft, there’s been a broken sewer leaking into the river for the past three years.”

Months after the launch of ambitious climate restoration efforts, the persistent contamination continues to defy clean-up initiatives. (Charity Kilei)

Months after the launch of ambitious climate restoration efforts, the persistent contamination continues to defy clean-up initiatives. (Charity Kilei)

Musila points out that the open sewer continuously channels contaminated waste into the river, making it impossible for any form of aquatic life to survive.

“For any animal to survive in the Nairobi River, it would take the grace of God. The current state reflects a lack of seriousness from the government because they’re not addressing the problem at its source,” he says.

He adds that while discarded bags and other trash contribute to the pollution, the primary issue lies with untreated waste flowing directly into the river. For Musila, tackling these systemic issues is critical to achieving meaningful change.

John Nzioki, another Nairobi resident, sheds light on the challenges posed by open sewers, which extend far beyond the Nairobi River to affect residential areas. He notes that many broken sewer lines are either redirected to the river or left unattended for extended periods.

“Recently, a sewer line was broken, and waste flowed from the residential area to the river. It took months before it was repaired. Garbage is another issue—we pile it at a central spot, but it’s rarely collected, sometimes for months,” Nzioki explains.

Faced with such neglect, residents often have no choice but to dispose of their waste in the river—not out of willingness, but desperation.

“Many of these services, like prompt sewer repairs or rubbish collection, don’t reach us. At night, rubbish from neighbouring residential areas is even dumped into the river under cover of darkness,” he adds.

Nzioki acknowledges that the clean-up efforts have created job opportunities for young people, which he considers a positive development. However, he emphasises the need for proper tools, designated waste management areas, and reliable service delivery to make the exercise effective.

“If you inspect some of the gunny sacks in the river, you’ll find medical waste, including supplies and even foetuses. Everything is just dumped into the river, hoping it will wash away. We need proper structures to ensure this clean-up has lasting results,” he says.

Residents claim the open sewer continuously channels contaminated waste into the Nairobi River. (Charity Kilei)

Residents claim the open sewer continuously channels contaminated waste into the Nairobi River. (Charity Kilei)

An anonymous official revealed that the lack of a proper waste collection system and unaddressed structural issues continue to undermine efforts to rehabilitate the river.

“The individuals responsible for opening sewers and redirecting waste to the river are known, but the initiative to hold them accountable has been slow. This negligence keeps sabotaging the progress of the Nairobi River clean-up,” the official noted.

Residents and stakeholders agree that while the clean-up efforts are commendable, meaningful change requires addressing systemic gaps, improving service delivery, and enforcing accountability to prevent the cycle of pollution from repeating itself.

The lack of proper waste management systems in Nairobi has left residents with limited options for disposal. Many dump their rubbish into open sewers that eventually flow into the Nairobi River, while others burn their waste or throw it directly into the river, exacerbating the environmental and health crises in the area.

Despite ongoing efforts under the Climate Works initiative, progress in cleaning the Nairobi River has been sluggish. The clean-up process is hindered by individuals who continue to dump rubbish into the river, often at night. This cyclical pollution undermines every effort to restore the river, making long-term improvements elusive.

The Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, and Forestry has identified 145 facilities along the Nairobi River basin that are discharging industrial effluent into the water.

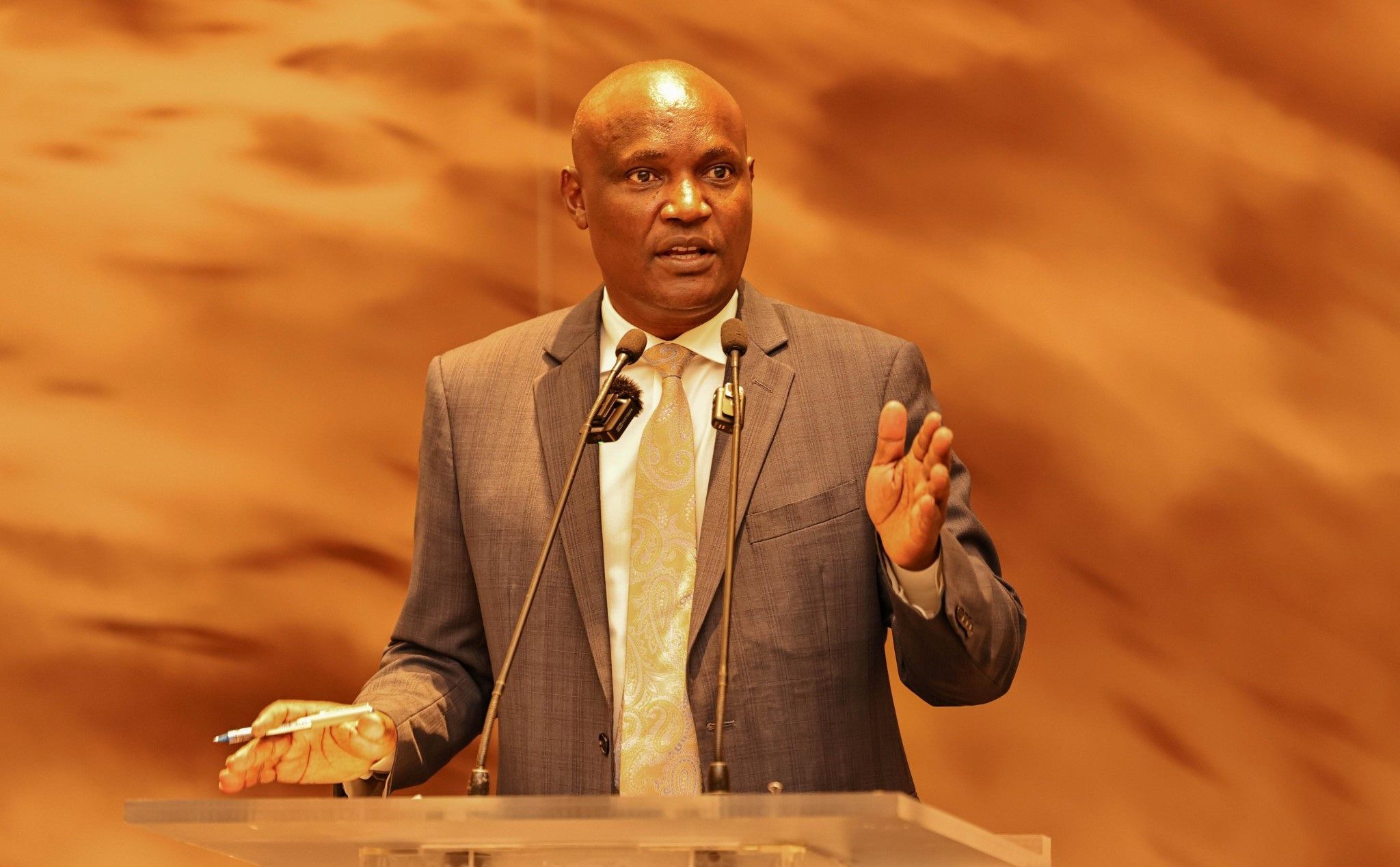

In response, President William Ruto issued a stern warning, pledging accountability for polluters.

“Entities polluting our rivers—industries, manufacturers, and those discharging raw sewage and solid waste—will all be held to account,” he declared.

Nairobi River spans approximately 2,500 square kilometres. (Charity Kilei)

Nairobi River spans approximately 2,500 square kilometres. (Charity Kilei)

Efforts to clean the Nairobi River, which spans approximately 2,500 square kilometres, have faced repeated setbacks over the years. The Nairobi River Basin Programme launched in 1999, and the Nairobi Regeneration Programme under former President Uhuru Kenyatta both failed to deliver lasting results.

Environment Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale revealed that many of the facilities polluting the river do so because their effluent treatment plants are not functioning properly.

While informal settlements near the river have often been blamed for pollution, Duale clarified that these areas contribute less than 1% of the total contamination, primarily through manageable organic waste.

In contrast, 145 industries, slaughterhouses, and non-compliant real estate developments account for approximately 90% of the pollution.

The National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) has mapped these facilities, issued restoration orders, and threatened closures for those failing to meet environmental standards.

Top Stories Today