Lenacapavir, long-acting injectables show strong potential in HIV treatment

New data from African trials and global studies show long-acting HIV injections can match daily pills for viral suppression and prevention, with fewer doses and potential benefits for stigma and adherence.

Innovation is rapidly reshaping the landscape of HIV treatment, opening bold new possibilities at a time when global funding cuts threaten to stall progress.

On World AIDS Day, breakthrough therapies are taking centre stage, offering a glimpse of what the next era of HIV care could look like.

They include the IMPALA study, a phase 3b, open-label, randomised controlled trial conducted in Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa in 2024, which enrolled 540 adults living with HIV-1 who had previously struggled with adherence to daily oral antiretroviral therapy (ART) or had other indicators of unstable engagement in care.

Participants were only eligible if they had achieved viral suppression on standard oral ART during a screening phase.

Once enrolled, they were randomised to either continue their daily oral regimen or switch to a long-acting injectable combination of cabotegravir and rilpivirine, administered intramuscularly every two months. The primary evaluation point was at 48 weeks, measuring viral suppression and safety.

The findings were remarkable. At 48 weeks, 91.4 per cent of participants receiving the injectable regimen maintained viral loads below 50 copies per millilitre, compared with 89.2 per cent of those on oral ART. This difference fell well within the pre-defined non-inferiority margin, confirming that the injectable regimen was as effective as daily oral therapy.

Confirmed virologic failures were rare, occurring in only five participants in the injectable arm. In most of these cases, viral sequencing revealed high-level resistance to cabotegravir, and in some instances, to rilpivirine.

Importantly, participants reported a strong preference for the long-acting regimen, citing convenience, improved privacy, and reduced stigma as key advantages. Injection-site reactions, such as mild pain or swelling, were common but generally well tolerated, and serious adverse events were rare.

However, while adherence to injections was high in the trial, missing or delayed doses could increase the risk of viral rebound and resistance in real-world settings. Finally, long-term data on the durability of viral suppression and safety in African populations remain limited, as follow-up beyond 24 months is still ongoing.

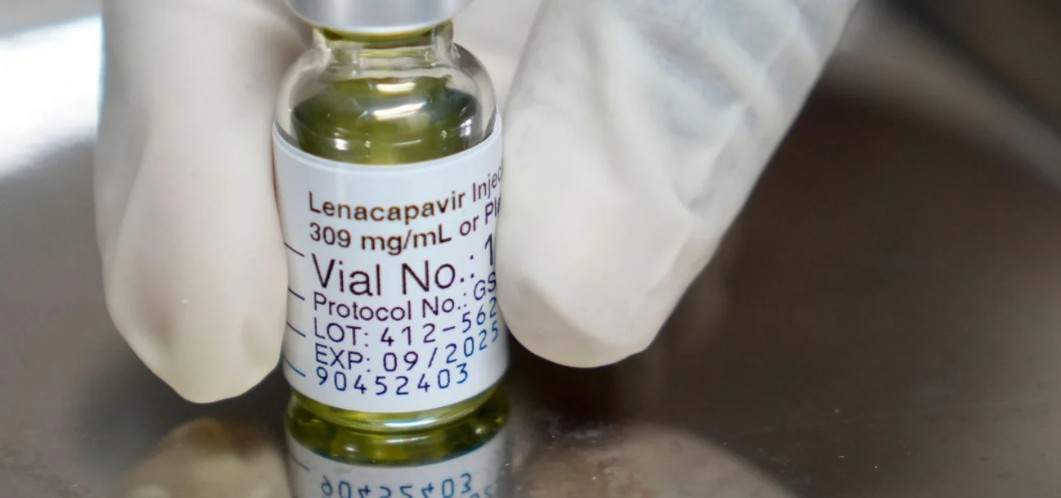

Meanwhile, Lenacapavir, an ultra-long-acting antiretroviral drug that has shown remarkable promise both for HIV prevention and treatment. It works as a capsid inhibitor, targeting the HIV-1 virus in a way that differs from traditional antiretrovirals, which makes it a valuable addition to the HIV treatment toolkit.

One of the most striking features of Lenacapavir is its dosing schedule: it can be administered as a subcutaneous injection once every six months, drastically reducing the burden of daily pill-taking for people at risk of or living with HIV.

For prevention, Lenacapavir has been tested as part of the PURPOSE 2 Trial, which enrolled over 2,000 participants across multiple countries. The study found that individuals receiving the twice-yearly injection experienced a 96 per cent reduction in the risk of acquiring HIV compared with the background HIV incidence, with only two new infections reported among those receiving the drug.

This level of efficacy far surpasses traditional daily oral PrEP options in real-world settings where adherence can be a challenge.

In terms of treatment, Lenacapavir has also been studied in combination with other long-acting therapies for people living with HIV, particularly those with multidrug-resistant virus or difficulty adhering to daily oral ART.

Early-phase trials suggest that Lenacapavir, when combined with other antiretrovirals or broadly neutralising antibodies, can maintain viral suppression effectively over months, offering patients a more manageable, less frequent dosing schedule.

Despite these promising results, Lenacapavir is not without limitations. The long dosing interval requires strict adherence to injection schedules; missing an injection could lead to subtherapeutic drug levels, which may increase the risk of viral resistance. Additionally, as with all new therapies, long-term safety and real-world effectiveness in diverse populations still need further study.

Kenya is set to begin offering Lenacapavir by early 2026, according to NASCOP and the Ministry of Health.

Health officials, however, emphasise that Lenacapavir is not intended to replace existing prevention or treatment methods, but rather to expand options and allow individuals to choose a regimen that best fits their lifestyle, risk profile, and ability to maintain adherence.

Beyond established injectables, the pipeline now includes even more futuristic and promising therapies.

For example, a recent 2025 study presented at CROI 2025 described an investigational regimen combining Lenacapavir with broadly neutralising antibodies (bNAbs). This combination, administered twice a year, met its primary endpoints in a Phase 2 clinical trial, achieving viral suppression comparable to standard ART

If further trials succeed, such therapies could offer people living with HIV:

A drastically simplified regimen: fewer clinic visits, less frequent doses, and potentially longer-lasting viral suppression. That could be especially beneficial for individuals in low-resource settings or those who struggle with regular adherence, travel, or stigma.

Improved adherence and greater convenience: For many people, especially in communities where access to health care is inconsistent, or where stigma and busy lives make daily pills hard to maintain, long-acting injectables (every 2 months, 4 months, or even 6 months) could dramatically increase adherence and viral suppression.

Reduced stigma and increased privacy: Injectable regimens are more discreet. People don’t have to keep pills or worry about hiding them, which can reduce stigma and make treatment more acceptable socially.

Expanded reach of prevention (PrEP): Long-acting PrEP options like Lenacapavir make it easier to protect populations at high risk, particularly where daily oral PrEP has had low uptake due to practical or social barriers.

Potentially transformative for resource-limited settings: The fewer clinic visits and simplified dosing could make HIV treatment and prevention more scalable, even in low-income or rural areas, where frequent access to care is challenging.

Toward a more flexible, tailored HIV care model: With multiple options (daily pills, monthly or bimonthly injectables, twice yearly regimens, combination therapies), HIV care becomes more adaptable to individual patient needs, lifestyles, and constraints.

Top Stories Today