Exclusive: Dr Juzar Hooker sheds light on Parkinson’s disease, the silent neurological disorder with no cure

Classic symptoms include tremors at rest, slowness of movement, rigidity, and postural instability. Neurologists use a careful combination of these signs, alongside patient history, to confirm the diagnosis.

Imagine living in a body that shakes uncontrollably while at the same time feels frozen in place.

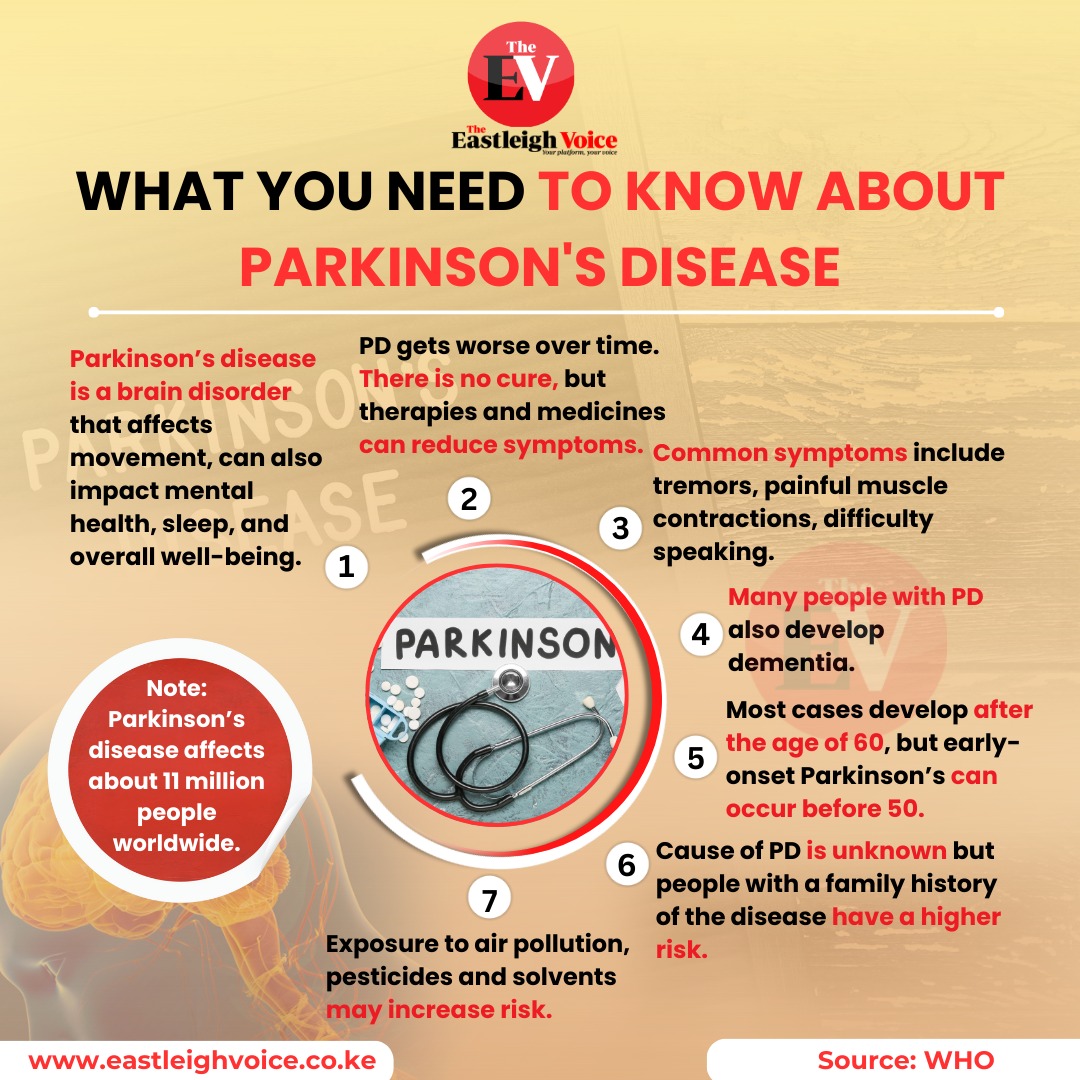

This scenario is the daily reality for over 11 million people worldwide suffering from Parkinson’s disease— a complex and often misunderstood movement disorder.

More To Read

- Nine common household items that could be silent killers

- Neurological disorders on the rise in low-and middle-income countries, warns WHO

- Poor sleep could age the brain faster, study suggests

- New study links oral hygiene to pancreatic cancer risk

- 10 minutes of sunlight: The science-backed brain boost you’re likely overlooking

- Norwegian study shows women with more children have lower cancer risk

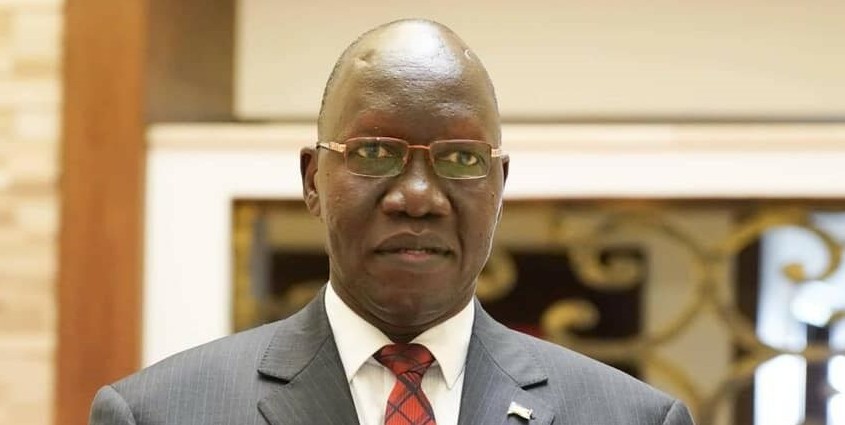

Recently, Dr Juzar Hooker, a consulting neurologist at Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, whose special interest lies in movement disorders, spoke to The Eastleigh Voice and shared deep insights into Parkinson’s disease, its causes, warning signs, diagnosis, treatment, and challenges facing patients in Kenya.

Parkinson’s disease is, as Dr. Hooker describes, an "interesting" movement disorder because it paradoxically involves both too much and too little movement.

“It’s a condition of too much movement tremors and too little movement at the same time,” he explains. Patients often walk slowly, speak softly, become rigid, and struggle with balance. It’s not just the body that suffers. Parkinson’s changes the very way a person exists in the world.

What really happens in the brain?

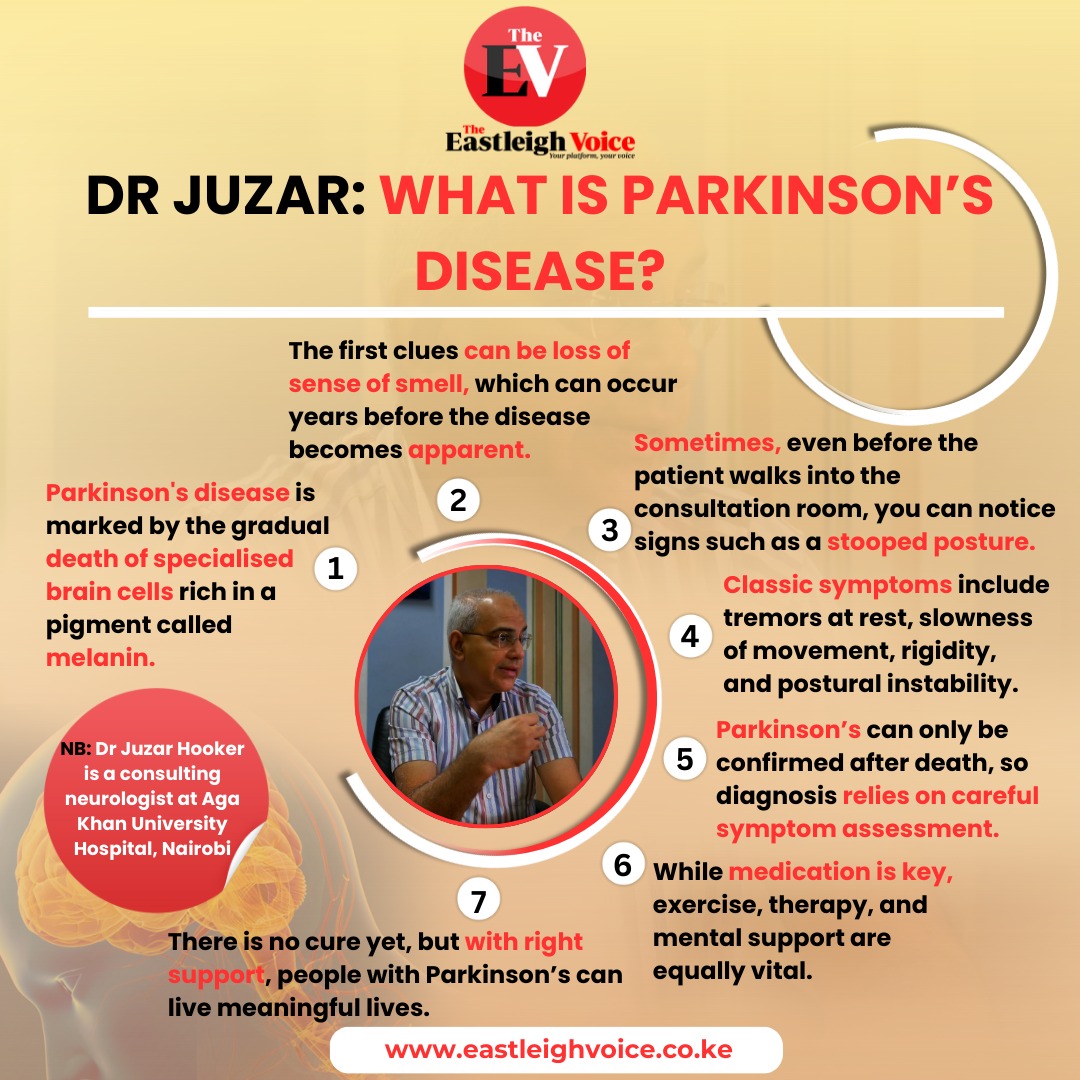

The root of Parkinson’s disease lies deep within the brain. Dr Hooker explains the disease is marked by the gradual death of specialised brain cells rich in a pigment called melanin. These cells produce dopamine, a critical chemical messenger that controls movement and coordination.

The loss of dopamine-producing cells doesn’t happen overnight. Interestingly, research suggests the loss of these brain cells may begin up to 20 years before symptoms appear. “Initially, our brains compensate, so the symptoms stay hidden. However, once we lose a critical number of cells, the signs start to emerge," according to Dr Hooker.

Dr Juzar Hooker, a leading consulting neurologist at Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi. (Photo: Ahmed Shafat)

Dr Juzar Hooker, a leading consulting neurologist at Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi. (Photo: Ahmed Shafat)

Why these cells die remains a medical mystery. Scientists know that misfolded proteins accumulate inside the brain, clumping together and interfering with normal cell function. However, whether these clumps are the cause or result of Parkinson’s is still unclear. Certain risk factors have been identified; exposure to pesticides, advancing age, and genetic mutations all increase the risk of developing the disease. However, the complete solution to Parkinson's remains a puzzle.

Early warning signs: The symptoms we often miss

One of the most concerning aspects of Parkinson’s is how silently it begins. Years before tremors or stiffness set in, subtle clues may be present – clues that are often dismissed or overlooked.

According to Dr Hooker, among the earliest warning signs is a loss of the sense of smell. While this symptom can occur with conditions like COVID-19 (and typically recovers), in Parkinson’s, the loss is more profound and long-lasting.

“One of the first clues can be a loss of the sense of smell,” says Dr Hooker. “This can happen years before the disease becomes apparent.”

Another intriguing early symptom is known as "dream enactment disorder". Normally, when we dream, our bodies are effectively paralysed, preventing us from physically acting out our dreams. But in people who later develop Parkinson’s, this natural paralysis fails.

Individuals may kick, punch, or thrash about in their sleep, often without any memory of doing so—something that bed partners usually notice first.

Constipation is another early sign, though Dr Hooker cautions that constipation is common in the general population and not always linked to Parkinson’s. Still, its presence alongside other symptoms should not be ignored.

How Parkinson’s is diagnosed

Parkinson’s disease remains a clinical diagnosis, meaning doctors largely rely on a patient’s history and physical examination rather than laboratory tests. "Sometimes, even before the patient walks into the consultation room, you can notice signs such as a stooped posture or shuffling walk," Dr Hooker notes.

Classic symptoms include tremors at rest, slowness of movement (bradykinesia), rigidity, and postural instability. Neurologists use a careful combination of these signs, alongside patient history, to confirm the diagnosis.

When uncertainty exists, brain imaging like MRI or CT scans can rule out other conditions. More specialised scans, such as the DaTscan (Dopamine Transporter Scan), now available at Aga Khan University Hospital, offer further confirmation by showing dopamine activity in the brain. Nevertheless, the diagnosis remains heavily reliant on clinical expertise. Absolute certainty can only be achieved by examining brain tissue after death, a practice reserved for research purposes.

“The only way to be absolutely certain is to examine the brain after death,” says Dr Hooker. “So for now, it’s a matter of piecing the symptoms together carefully.”

Treatment options: What’s available in Kenya?

Managing Parkinson’s requires a multifaceted approach. In Kenya, however, treatment options are somewhat limited, both in availability and accessibility.

Exercise and physical therapy, according to Dr Hooker, are crucial but often underutilised tools. Regular exercise helps not only to ease symptoms but may also slow disease progression. Speech therapy, occupational therapy, and psychological support are equally important.

Yet, as Dr Hooker points out, the number of specialised therapists in Kenya is very small, and access to such services is often restricted to major cities.

“There’s a lot of emphasis on medication, but physical exercise, physiotherapy, speech therapy, and psychological support are just as important,” Dr Hooker tells The Eastleigh Voice.

When it comes to medication, the cornerstone of treatment is replacing the lost dopamine. The most common drug used is levodopa, often sold under brand names like Sinemet. Levodopa helps restore dopamine levels, dramatically improving symptoms for many patients.

But availability is inconsistent. Random spot checks conducted by Dr Hooker and his colleagues found that even in Nairobi, many pharmacies don’t stock these vital drugs, and outside the city, the situation is even worse. Cost is another major hurdle, with many patients unable to afford long-term treatment.

How the disease progresses

Parkinson’s is a progressive, degenerative disease. Over time, symptoms worsen, and daily activities become increasingly difficult. Tasks most of us take for granted, like dressing, eating, or even smiling, can become monumental challenges for Parkinson’s patients.

While medications can greatly improve quality of life, they do not halt the disease’s progression. As time goes on, the effectiveness of medications may wane, and new complications, such as involuntary movements (dyskinesias) or medication side effects, may emerge.

Despite this grim reality, early diagnosis and comprehensive management can make a world of difference.

“There is no cure yet,” Dr Hooker says. “But with the right support, people with Parkinson’s can live meaningful lives.”

The way forward: Awareness, access, and research

Parkinson’s disease doesn’t just affect the body; it impacts families, communities, and healthcare systems. Raising awareness about early warning signs could lead to earlier diagnosis and better outcomes. Enhancing access to affordable medications and specialist services is equally vital.

Dr Hooker calls for more investment in training healthcare professionals, expanding therapy services, and supporting research initiatives. "Understanding why Parkinson’s develops and how to stop it is one of the great scientific challenges of our time," he says.

As the global burden of Parkinson’s disease continues to rise, Dr Hooker is calling for a shift in how society views and supports those affected, reminding the public that a diagnosis is not a reflection of personal failure.

“Parkinson’s disease is nobody’s fault,” said Dr Hooker during a recent awareness campaign. “It’s not because you’ve done something wrong or because someone has wronged you. It can happen to anyone.”

Citing examples of influential figures who lived with Parkinson’s, Dr Hooker pointed to the late Pope John Paul II. “He had Parkinson’s disease and continued to work for years until his demise. He contributed greatly to society, even in the face of the condition,” he said. “His life reminds us that a diagnosis should not diminish a person’s worth or their ability to make an impact.”

Dr Hooker emphasised the need for a collective response from medical professionals, families, and communities. “We should do everything we can to make people feel wanted, included, and supported,” he urged. “Having Parkinson’s doesn’t mean your contribution to society ends; in fact, it can mark the beginning of a new chapter in advocacy, awareness, and strength.”

In Kenya, as in many parts of the world, the battle against Parkinson’s is only just beginning. But with continued education, patient support, and medical advances, there is hope that one day this silent, slow-moving thief of movement and independence can be stopped in its tracks.

Top Stories Today