Democracy is all about political and historical contexts, not standards

The dubious profiling of Rwanda has been a common feature of Western reporting on Africa for the past 60 years.

Each democracy adapts to the political and historical contexts of its country and Rwanda’s democracy is no exception. In the upcoming general elections scheduled for July 15th, the Rwandan people will cast their vote to elect their president and representatives to the House of Representatives.

The current president, Paul Kagame, is expected to win by a landslide. He first became president in 2000, six years after the Rwandan Patriotic Front stopped the genocide under his leadership.

More To Read

- Rwanda extends military mandate in Mozambique's troubled north

- DR Congo: Rising insecurity in the east impedes diplomatic progress, Security Council hears

- Rwanda rejects Human Rights Watch allegations of backing M23 killings in DRC

- UN commander welcomes Rwandan troops to South Sudan

- ADF rebels kill at least 52 civilians in eastern DRC

- Rwanda gears up to host historic 2025 UCI Road World Championships in Africa

Western critics, journalists, and academics claim that Rwandan elections must be controlled because, in their view, no other “real democracies” have had their president elected with over 90 per cent of votes. To them, Paul Kagame’s recurring landslide victories since 2003 are “too good to be true”?

Those critics say that there is no “real opposition” in Rwanda and that a nation that elects its president with 90 or 95 per cent cannot be "healthy," as France 24 journalist Marc Perelman uttered in his recent interview with Paul Kagame.

To that Kagame responded, “Why should you be worried if somebody is elected with 90 or 15% if that is their context? In the end, it is the context that decides.”

When I tease my Rwandan friends about what those critics call “no real opposition”, they would retort in a sarcastic tone: “But what is there to oppose in my country... universal healthcare, free education, access to employment, quotas for the seats in Parliament for women and persons with disability, economic development, sustainable environment policies, nation-wide power, internet access, and national security.

The social and economic achievements my Rwandan friends point to cannot be taken for granted. Rwanda was born from ashes in the wake of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, and in just 30 years, has achieved a level of equality in access to services that no other country in the world, including in the Global North, could dream of.

Most importantly, after experiencing what some have called a “genocide of proximity”, where neighbours had killed neighbours, teachers had killed students, husbands had killed wives, and mothers had killed sons, Rwandans, with effective leadership and governance, were able to rebuild the nation on unity and reconciliation, as victims and perpetrators learned to live together again and rebuild their future through collective effort.

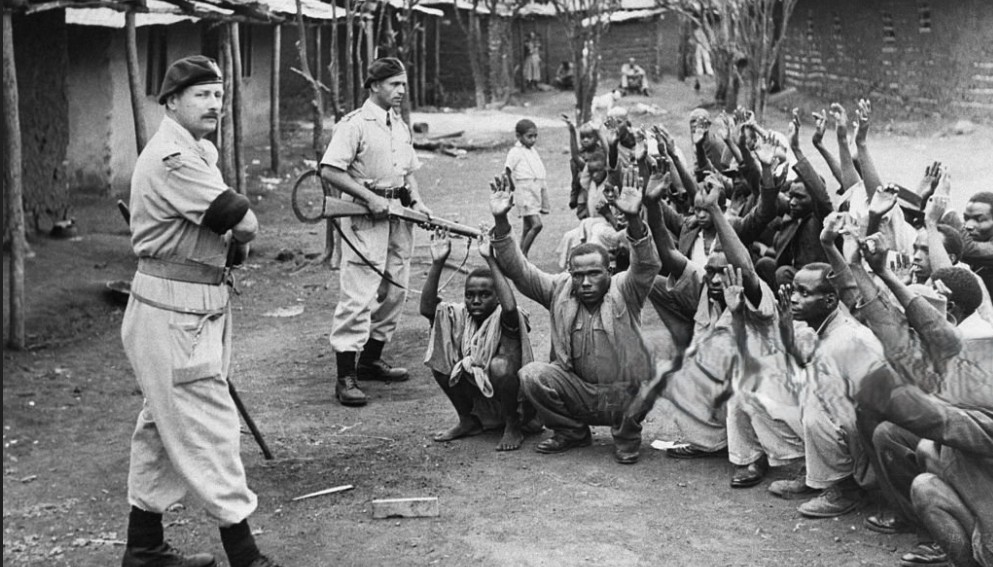

The dubious profiling of Rwanda has been a common feature of Western reporting on Africa for the past 60 years. Western media and analysts have become accustomed to presenting those African post-colonial leaders, who do not follow a certain Western “democratic standard” as “dictators”.

Supporters of Rwanda's President Paul Kagame of the ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) party attend the first campaign rally ahead of the July Presidential vote at Busogo, Musanze District, Rwanda, June 22, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Jean Bizimana)

Supporters of Rwanda's President Paul Kagame of the ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) party attend the first campaign rally ahead of the July Presidential vote at Busogo, Musanze District, Rwanda, June 22, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Jean Bizimana)Supporters of Rwanda's President Paul Kagame of the ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) party attend the first campaign rally ahead of the July Presidential vote at Busogo, Musanze District, Rwanda, June 22, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Jean Bizimana)

But what exactly is the Western standard of democracy, and to what extent might Rwanda, with its unique historical trajectory of injustice, be worthy of following a one-size-fits-all Western democratic model?

As a global citizen who has lived in 5 different democracies on 3 different continents, I consider that the Western critics’ assessment of the Rwandan elections ignores that democracies are indeed shaped by context. In fact, Western observers of Rwanda, due to their implicit or explicit racial bias, have chosen to ignore that even in the West, there is no one-size-fits-all-democracy, because, as Paul Kagame stated during this presidential campaign, democracy is about “freedom of choice”.

A good example of this statement by Paul Kagame is the 2002 French presidential election. I was then 22 years old and a first-time voter. I had been a naturalised French citizen, having emigrated to France as a political refugee in 1992 from war-torn Bosnia, then a province of my native Yugoslavia.

That election was the first time that the far-right candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen had made it to the second round against then-president Jacques Chirac, who was on the centre-right of the French political spectrum. As a former immigrant, like most of my generation, I was a supporter of the progressive left.

Whereas Le Pen was an anti-immigrant, chauvinistic, and racist candidate, Chirac was known for his criticism of immigrants, whom he accused of “profiting” from the French social welfare system “at the expense of French nationals”.

This moment in the history of French democracy was a wake-up call for the French people, who rushed to the polls regardless of their political affiliation, to defeat the would-be fascist government of Jean-Marie Le Pen. Chirac won the election with 82.21% of the vote, a percentage that Marc Perelman might call “unhealthy”, but the Western world was relieved, and warmly celebrated Chirac’s victory.

The 2002 French elections were just one example among many of how democracy is shaped by context. The same fascist ideology that the French voted to defeat in 2002 led to the mass killing of 1 million Rwandans in 1994. That ideology still looms large, promoted by people like Victoire Ingabire, whose political party is called “opposition” by those same Western critics.

So when Paul Kagame is elected with more than 90% of the vote, it is a life-or-death situation for the Rwandan people, who, through their freedom of choice, have chosen unity, reconciliation, and security over division and hate.

French President Emmanuel Macron greets Rwanda's President Paul Kagame as he arrives to attend the Global Forum for Vaccine Sovereignty and Innovation at the French Foreign Ministry, the Quai d'Orsay, in Paris, France, June 20, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Dylan Martinez/Pool)

French President Emmanuel Macron greets Rwanda's President Paul Kagame as he arrives to attend the Global Forum for Vaccine Sovereignty and Innovation at the French Foreign Ministry, the Quai d'Orsay, in Paris, France, June 20, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Dylan Martinez/Pool)French President Emmanuel Macron greets Rwanda's President Paul Kagame as he arrives to attend the Global Forum for Vaccine Sovereignty and Innovation at the French Foreign Ministry, the Quai d'Orsay, in Paris, France, June 20, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Dylan Martinez/Pool)

Courtesy - Aljazeera

Top Stories Today