Doctors Without Borders sounds alarm as mentally ill detained in South Sudan prisons

With few psychiatrists and no proper facilities, desperate families in South Sudan are turning to prisons to confine loved ones battling mental illness.

Families in South Sudan are increasingly resorting to imprisoning relatives with mental health conditions due to a severe shortage of psychiatric services, the humanitarian group Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has warned.

In a statement on Monday, MSF—also known as Doctors Without Borders—said that some patients in Malakal suffering from psychosis, bipolar disorder, and depression are being detained in local prisons because of the lack of specialised mental health facilities.

More To Read

- Millions of lives at risk, warn UN food agencies, as hunger crisis worsens

- South Sudan President ousts vice president in abrupt purge, deepening uncertainty in Juba

- Stakes rise for South Sudan: What’s happening, and why it matters

- President Kiir sacks Petroleum Undersecretary after a week in office

- MSF resumes critical medical activities in South Sudan's Yei County

- Exhibition brings to life the untold suffering of Africans crossing to Europe through Libya

The organisation, which runs mental health programmes at Malakal Teaching Hospital and the Central Prison, described the practice as a “desperate last resort” for families unable to access professional care.

“In many cases, detention centres become the only places where those with severe symptoms can receive care or be kept safe,” said Laura Ximena, MSF’s mental health activity manager in Malakal.

“While this is far from ideal, it reflects the urgent need for enhanced mental health infrastructure in the region.”

Between January and August 2025, MSF provided 1,130 mental health consultations in Malakal—761 for women and 369 for men. Of these, 12 patients reported having suicidal thoughts, with April recording the highest number of cases.

Severe psychological trauma

MSF noted that survivors of sexual and gender-based violence are among those experiencing severe psychological trauma but often lack access to both mental health and legal support. The organisation warned that without adequate services, many survivors remain untreated, deepening their suffering and isolation.

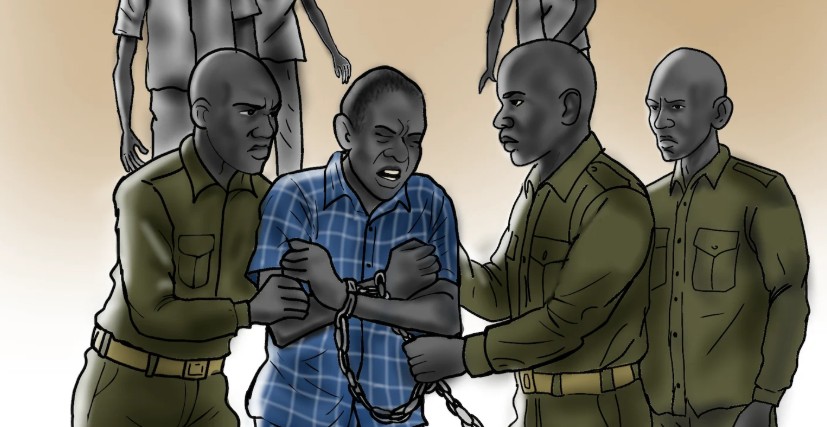

One such case is that of Samat Nyuk, whose family sent him to prison after traditional remedies failed to ease his psychosis. He spent several weeks in isolation before receiving treatment from MSF, which continues to provide him with medication and counselling.

“I knew I was unwell, but not a criminal. I needed support, not punishment. What hurt the most was that my own family chose prison for me instead of treatment,” he told MSF.

Mental health services in South Sudan remain critically underfunded, with few trained professionals and limited access to essential medicines.

The lack of proper facilities has forced prisons to serve as makeshift holding centres for mentally ill individuals, where conditions are harsh and treatment options are minimal.

MSF said it will continue advocating for the integration of mental health care into all levels of South Sudan’s health system, stressing the importance of sustained funding, community awareness, and respect for patients’ dignity.

“Individuals with mental health conditions deserve to be treated as persons with dignity, and not resort to detention centres where they can be associated with criminals,” Ximena said.

Top Stories Today