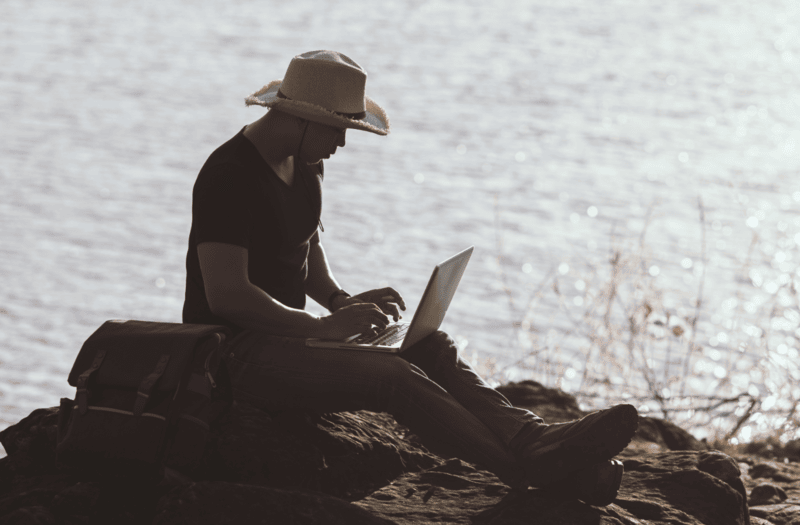

Work anywhere, live everywhere – Inside the rise of the young digital nomads

Improved access to remote jobs, better tech infrastructure, and a hunger for lifestyle freedom are driving the movement, especially among Gen Z and millennials.

From beach cafés in Bali to rooftop co-working spaces in Nairobi, a new generation of workers is redefining what it means to have a “job”.

They are called digital nomads – young professionals who work remotely while travelling the world – and their numbers have surged, especially post-COVID.

“For me, it started with burnout at work. Imagine sitting all day in front of a screen, going home, and just waiting for your salary,” says 28-year-old Munyao K, a freelance graphic designer originally from Nanyuki.

“I was tired of the routine. I love travelling and exploring new places. So, I quit my job as a banker and searched for a remote role. Once remote work became more accepted, I packed my bags and left for Cape Town. That was two years ago, and I haven’t looked back.”

Since then, Munyao has worked in over 13 countries, including Portugal, Thailand, and Rwanda.

He earns a living designing logos and brand kits for international clients via platforms like Upwork and Fiverr.

But the shift to life on the road wasn’t spontaneous. “I didn’t just pack a bag and leave. It took months of planning, financial discipline, and a huge leap of faith.”

He sold everything in his house and relied on savings from his banking job. “I even gave myself a seven-month allowance,” he says.

During that time, he juggled full-time work while testing out remote gigs on evenings and weekends. “I had to see if it was viable. Once I started earning from online gigs, that’s when I seriously considered quitting.”

He researched visa requirements, budgeting strategies, and built reliable client relationships before fully committing. “I just need a laptop, good Wi-Fi, and a plug adapter,” he says with a laugh.

The Freedom – and the hustle

It’s easy to be seduced by the curated Instagram reels – laptops on beach beds, lattes in Bali, early morning hikes before Zoom calls.

But behind the aesthetic is a lifestyle that demands constant adjustment and strict self-discipline.

“People glamorise this lifestyle,” Munyao says. “They don’t see the missed flights, the 2 am client calls, the dodgy Airbnb Wi-Fi.”

While the freedom to work from anywhere is the main draw, it comes at a cost. Digital nomads must navigate shifting time zones, unfamiliar cultures, and logistical headaches.

“It’s beautiful, but also exhausting,” he admits. “One week you’re in Nairobi, the next you’re figuring out SIM cards in Ho Chi Minh City.”

He recalls taking important video calls from hostel lobbies, airports, and even public parks – always on the hunt for stable internet.

“The hustle is real. You’re your IT, admin, and HR. Everything relies on how well you manage yourself.”

Even leisure can feel like labour. “You might be in a luxury hotel, but your mind is still ticking: ‘work, work, work’. There’s always a deadline or client call looming.”

Staying visible online is a necessity.

“Content creation helps keep you relevant, especially if you’re freelancing or building a brand. You’re always posting, engaging, and strategising. Some of my friends make money from TikTok and YouTube, even getting client deals through simple posts. I’m a bit shy about it – maybe I’ll try this year,” he laughs.

True rest, Munyao admits, becomes rare. “When you’re managing your own business remotely, it’s hard to switch off. The pressure to perform never truly fades.”

“It’s not a holiday. If anything, it’s working harder – but on your own terms.”

That’s the trade-off, he says. “You gain freedom, but you carry your entire life and career in a backpack.”

The logistics of being a digital nomad aren’t as effortless as TikTok might suggest. Many juggle tourist visas and travel frequently to avoid overstaying.

Others seek out “digital nomad visas” – special permits allowing remote workers to legally stay longer.

“Countries like Portugal, Estonia, and even Rwanda offer digital nomad visas with incentives to attract remote professionals,” says David Kariuki, an immigration consultant in Nairobi.

“These governments recognise the economic benefits of remote workers and are adjusting immigration policies accordingly.”

But barriers remain.

“Many young Kenyans are unaware these options exist. Even if they are, most don’t meet the requirements,” Kariuki explains.

“Many freelancers lack the consistent income or documentation to prove financial stability – a key condition for most of these visas.”

Monthly income requirements vary, typically ranging from Sh186,000 to Sh587,500. For example, Portugal requires around Sh186,000, while Barbados demands up to Sh587,500.

Mexico and Thailand fall between Sh228,000 and Sh282,000, while countries like Dubai and Estonia require over Sh500,000.

And then there’s the emotional toll. “Loneliness creeps in,” Munyao says. “You’re far from family. Making meaningful connections is hard – people are always on the move.”

Dating can be tricky too. “You might meet someone through apps like Tinder, but you have to be honest about not staying long. You have to guard your emotions.”

Why the trend is growing

A 2024 MBO Partners report estimates that over 40 million people globally now live as digital nomads, with Africa’s share growing steadily.

South Africa was the fourth most popular destination for digital nomads in 2024, and Kenya is actively embracing the trend. Earlier this year, the Kenyan government launched a Digital Nomad Work Permit.

Improved access to remote jobs, better tech infrastructure, and a hunger for lifestyle freedom are driving the movement, especially among Gen Z and millennials.

“Young Kenyans are realising they don’t need to be stuck in traffic on Thika Road to earn a living,” says Janet Gichuki, a remote worker.

“You can work from Diani this month, Kampala the next. I’m not there yet, but I’m working towards it.”

What’s Next?

Governments and start-ups are taking note.

Nairobi recently hosted a Digital Nomad Summit, and co-working hostels are emerging in places like Mombasa and Nanyuki.

Still, challenges persist – unreliable Wi-Fi, lack of legal frameworks, and family pressure to “settle down”.

“I miss ugali and my mum,” Munyao says with a grin.

“But this is the life I want – freedom, no children (for now), creativity, and a chance to see the world while building my career.”

“At the end of the day, what will I tell my kids I did with my life? Sit in an office, wait for a salary? That, to me, is a sad life.”

Top Stories Today