Over a third of children with congenital heart disease die within a year at KNH, study finds

The study shows that most patients faced long delays before receiving treatment, with only 69 patients (37 per cent) undergoing the recommended surgery within one year.

At least 36.1 per cent of children diagnosed with congenital heart disease (CHD) at Kenyatta National Hospital died within a year of diagnosis, largely due to delayed surgical intervention and limited access to specialised treatment.

According to a study conducted by researchers from the University of Nairobi and Kenyatta National Hospital, only 37 per cent of the patients received the recommended surgery within a year, with most waiting nearly two months for treatment, while others succumbed before intervention.

More To Read

- Watermelon’s best-kept secret: Seeds and rind could transform your health, researchers say

- Microplastics and heart disease: Emerging evidence of a hidden cardiovascular threat

- How follow-up programmes bridge treatment gap in non-communicable diseases

- New study finds long-term use of sleep pill melatonin may raise risk of heart failure and death

- Study links excess screen time in children to higher heart and metabolic risk

- Viral infections linked to higher risk of heart attacks and strokes

The study reviewed 1,703 medical records of patients admitted with CHD between January 2016 and December 2021.

At diagnosis, more than half (53.6 per cent) of the patients were aged below one year, while 56.6 per cent were male.

Congenital heart disease refers to structural abnormalities in the heart present at birth, which can range from mild defects like small holes in the heart to severe malformations involving missing or poorly developed chambers and valves.

Long delays

The study shows that most patients faced long delays before receiving treatment, with only 69 patients (37 per cent) undergoing the recommended surgery within one year.

The average waiting time for surgery was 59 days, ranging between 10 and 208 days. Another 67 per cent of those recommended for catheterisation, a less invasive heart procedure, underwent it within a median of 95 days.

For patients referred abroad, the wait was even longer, averaging 349 days before receiving care.

“The lengthy time period between diagnosis and intervention is mainly due to issues related to access and affordability. Delayed diagnosis and long waiting time to intervention may lead to deaths before intervention is undertaken or poor outcomes when the intervention is finally undertaken,” reads the report.

Severe shortage of resources

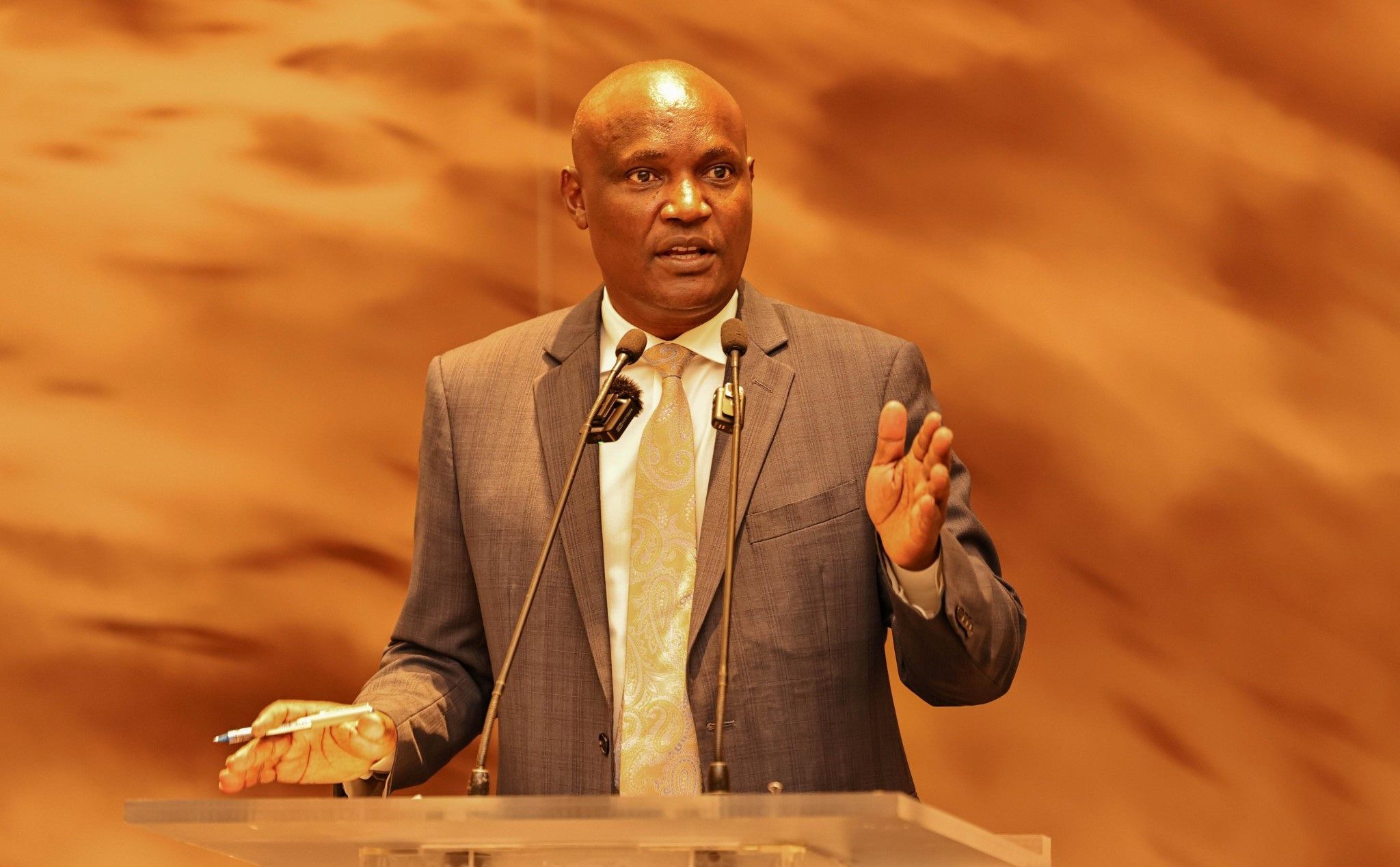

Lead author, Dr Bonface Osano, a paediatric cardiologist and lecturer at the University of Nairobi, said the findings reflect the severe shortage of resources and specialists available to manage CHD in Kenya’s public hospitals.

“The majority (62.9 per cent) of patients recommended for surgery did not undergo the surgery,” Osano said.

The study also found that older children and those with Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), a complex heart defect that reduces oxygen levels in the blood, were more likely to die than younger patients. The adjusted odds ratio for age-related mortality was 1.99, indicating nearly double the risk of death compared to infants.

In total, 961 patients (56.4 per cent) were alive one year after diagnosis, 615 (36.1 per cent) had died, and 127 (7.5 per cent) had unknown outcomes.

KNH is among the only three public hospitals in Kenya equipped to manage congenital heart conditions, the others being Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret and Coast General Teaching and Referral Hospital in Mombasa. However, the report highlights that the number of patients far exceeds the available medical capacity.

Too sick for surgery

Some families, the report adds, were informed that their children were too sick for surgery by the time they were diagnosed.

“At diagnosis, 57 were deemed inoperable and were counselled on palliative care,” reads the report.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), congenital heart disease affects between eight and 15 babies in every 1,000 live births globally. However, mortality rates are significantly higher in low and middle-income countries due to late diagnosis, limited access to diagnostic tools and high treatment costs.

The researchers noted that financial constraints, inadequate cardiac facilities and limited diagnostic capacity across the country are major contributors to delayed interventions and deaths. Many patients were referred from other hospitals to KNH, with 33.5 per cent coming from public hospitals, 22 per cent from within KNH and 11.6 per cent from private facilities.

The report also revealed that 43.2 per cent of patients were initially placed on medical management, while 14.1 per cent were recommended for surgery. However, more than 60 per cent of those who needed surgery never received it, either due to lack of funds or unavailable surgical slots.

“Few children with CHD receive the recommended interventions. Mortality for patients with CHD remains high, and many gaps in documentation need to be addressed,” the researchers said.

The report recommends that the Ministry of Health and hospital administrators prioritise early diagnosis, improved record-keeping, and faster access to life-saving cardiac procedures for children born with heart defects.

It further calls for investment in specialised training, better equipment and a national screening programme to detect congenital heart disease early, especially among newborns.

“There is a need to shorten the time taken from diagnosis to intervention for patients with CHD and to improve documentation for patients with CHD at KNH,” reads the report.

Top Stories Today