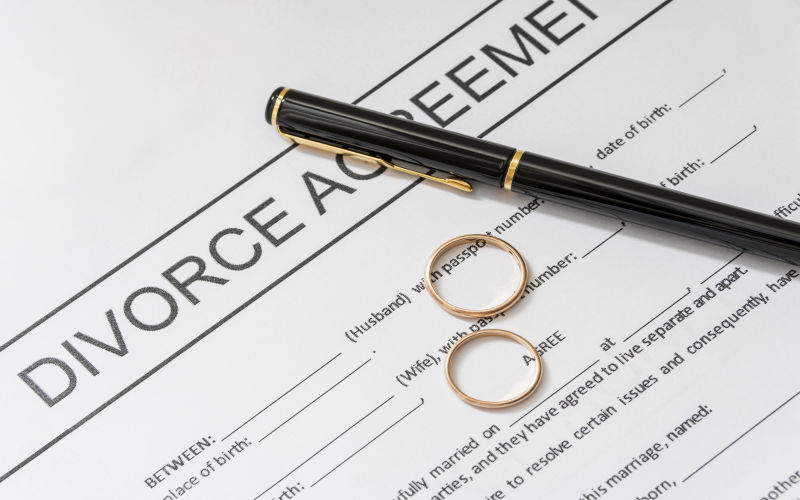

Explainer: What you should know about matrimonial suits and how property is divided

The Constitution and the Matrimonial Property Act espouse equality of spouses during and after marriage.

In Kenya, the division of matrimonial property after the dissolution of a marriage is guided by several legal principles.

Courts take into account the contribution of each spouse to the acquisition of matrimonial property, including financial and non-financial contributions, the length of the marriage, the age and health of the spouses, and the financial and social circumstances of both parties.

More To Read

- ‘They told them I was dead': A mother’s pain and the mental toll of family separation on children

- Fewer Kenyan women getting married, divorce rates on the rise - KNBS report

- Attorney General launches garden wedding services to enhance couples’ experience

- Registrar of Marriages orders submission of all certificates in 30 days effective September 3, 2024

- Married in absentia: Why some Muslim couples opt for representation marriage

- Man, 89, refused divorce by India's top court after 27-year case

What, therefore, constitutes matrimonial property?

It refers to any asset acquired by a spouse or jointly by both spouses during their marriage, including real estate and movable assets. However, assets acquired solely before marriage or inherited by one spouse are generally excluded from matrimonial property.

The Constitution and the Matrimonial Property Act espouse equality of spouses during and after marriage.

Thus, either spouse may file a petition for the division of matrimonial property as part of divorce proceedings or, in some cases, a separate suit if the marriage has broken down but not yet resulted in a formal divorce.

Of note, however, property acquired before the marriage or inherited by one spouse is not considered matrimonial property.

The Matrimonial Property Act of 2013, the primary legislation governing the Division of Matrimonial Property in Kenya, provides that matrimonial property should be divided fairly and equitably, taking into account the contributions of each spouse to the acquisition of the property.

Courts, however, have the discretion to consider the spouses' respective financial and social circumstances, among others.

On January 27, 2023, the Supreme Court ruled that marital property must be shared based on fairness and not per an automatic, fixed formula that imposes a 50-50 split.

The apex court noted that it will apportion and divide marital property only when the parties fulfil their obligation of proving what they are entitled to by way of contribution.

In so doing, the court will consider direct and indirect contributions based on fairness and conscience.

The case, which served as the maiden interpretation of Articles 45(1) and (3) of the Constitution concerning the mode of distribution of property acquired during a marriage, started at the High Court, made its way to the Court of Appeal and then finally to the Supreme Court. It began with a petition by a respondent claiming her share of the marital properties registered in the name of the applicant.

Although the High Court found that the respondent had failed to show direct contributions in the acquisition of the property registered in the name of the appellant, it acknowledged that she did in fact "make an indirect non-monetary contribution towards the family's welfare in the form of upkeep and welfare."

The court ruled that this entitled the respondent to a 30 per cent share of their matrimonial home and a 20 per cent share of the rental units constructed within the property.

Unsatisfied with the High Court's decision, the respondent successfully appealed the matter, and the Court of Appeal set aside the High Court's decision, ordering that the property be shared 50-50 between the appellant and respondent.

The court considered Articles 45(1) and (3) of the Constitution and the provisions of the Matrimonial Property Act, 2013, both of which were promulgated after the respondent filed the original summons at the High Court.

Top Stories Today