System glitches, lost lives: The human cost of SHA confusion

A few weeks ago, Raphael Ochieng experienced firsthand the heartbreaking chaos caused by the Social Health Insurance (SHA) system. He recalls when his colleague, gripped by panic, reached out for help. His wife was in labour and required urgent medical attention at a hospital in Nairobi.

Rushing to the facility, they believed she would receive the care she needed—only to be met with devastating news: she was not covered under SHA.

More To Read

Unaware of the new policy that classifies individuals aged 25 and above as a separate household, he had assumed, as was the case with NHIF, that his wife was still covered under SHA as his dependent, particularly since he had already made the required payments.

Despite their frantic efforts—rushing from one office to another, visiting cyber cafés to register her afresh, and even making the necessary payment—they hit yet another obstacle: the system was down. They were told to wait for it to update.

"It was painful watching her health deteriorate because of a failed system. We moved from one office to another, seeking answers, but no one could help," Ochieng recalls.

As her condition deteriorated, the hospital referred her to Kenyatta National Hospital. But within just ten minutes of arrival, she was pronounced dead.

"Now we are contributing to her funeral expenses because of confusion and system failures. Even after making out-of-pocket payments, we still lost her. It’s heartbreaking," he says.

Ochieng remembers how they moved from office to office, trying to resolve the issue, only to be met with dead ends. Payments were made, yet nothing worked.

"After witnessing all that happened, I can no longer trust SHA. If my loved one ever falls ill, I would rather sell everything I own or take out a loan to pay for their treatment than depend on a system that could cost them their life," he says.

He notes that out-of-pocket expenses have become the norm, and for many struggling in the tough economy, affording medical care is nearly impossible.

"If you don’t have money, you simply watch your loved one die because there’s nothing else you can do. Many times, people like me forgo treatment just to provide for our families—only the most critical illnesses get attention."

With ongoing challenges surrounding SHA, many Kenyans now face a dilemma: prioritising food or healthcare.

Joseph Waicungo, a manual labourer, speaks of the immense strain that healthcare costs have placed on him, often forcing him to travel to Kiambu County in search of affordable medical care. When illness strikes, his financial struggles make accessing treatment a daunting challenge.

"Recently, I fell ill, and despite meeting all the requirements, I still had to pay Sh1,500—money I didn't even have at the time," he recalls. "Sometimes, I’m left with a difficult choice: should I buy food for my expectant wife or seek treatment for myself?"

For Joseph, his wife’s health and well-being take priority. "I can’t ignore my wife’s condition and her need for medical care, but I can ignore mine. When I have to choose between buying food and buying medicine, I always choose food and pray for divine intervention."

Other Topics To Read

He admits that, at times, his only option is to rely on faith, hoping his illness does not take a fatal turn. He only visits the hospital when the situation becomes dire.

"My biggest concern right now is my wife, who is almost due to give birth. With all the confusion and challenges I’ve heard about in hospitals, I don’t even know how to prepare for it."

Joseph recounts how, on several occasions, he has prioritised buying food for his family over seeking medical care for himself. To endure the hunger, he relies on painkillers—his only temporary relief in a seemingly endless struggle.

The Social Health Authority (SHA) headquarters in Nairobi. (Photo: SHA)

The Social Health Authority (SHA) headquarters in Nairobi. (Photo: SHA)

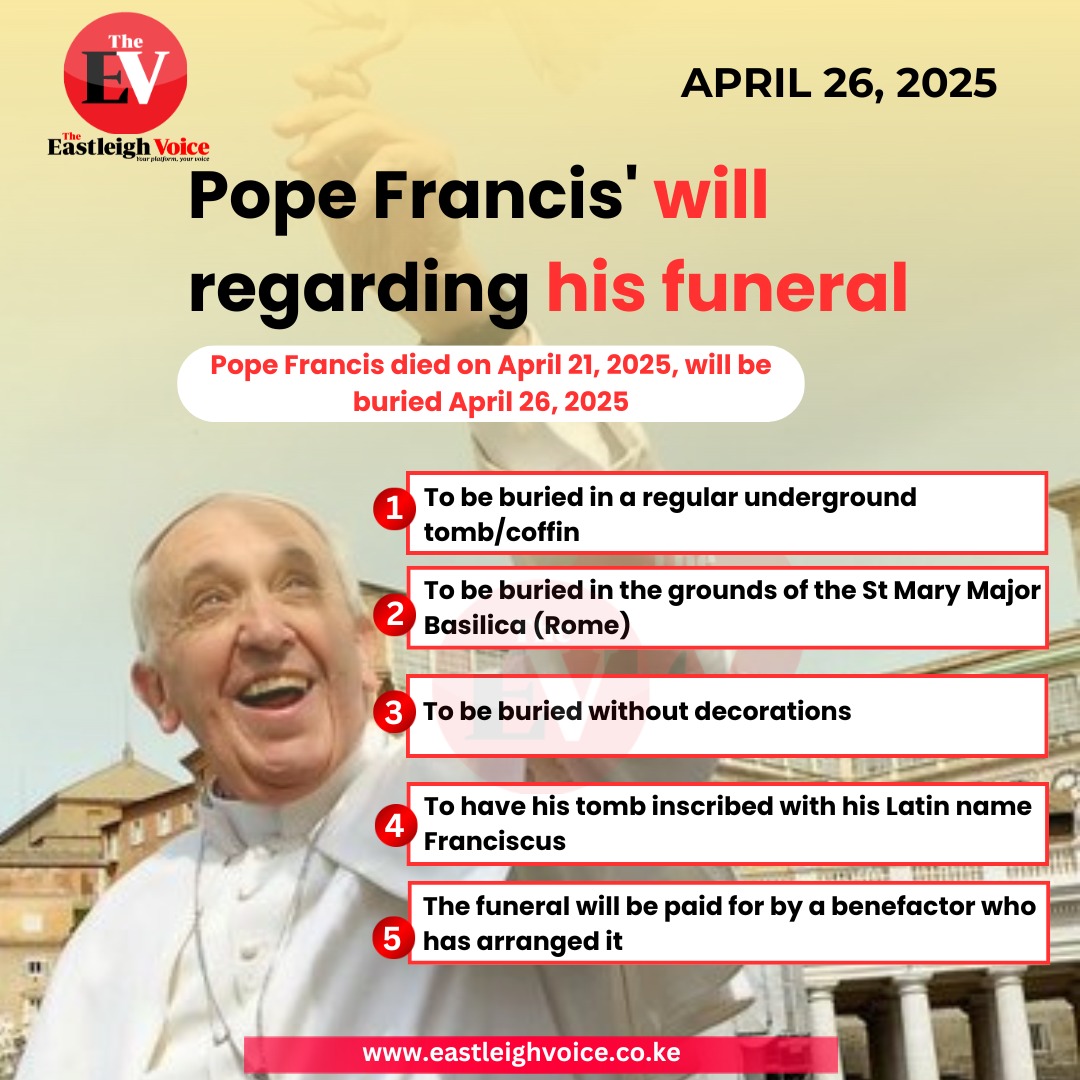

While the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) rollout enters its fourth month, approximately 4.3 million Kenyans who were automatically transitioned from NHIF have yet to update their profiles.

Despite the Ministry of Health reporting that 18.8 million Kenyans have registered, only 3.3 million have completed the mandatory scientific means testing to determine their eligibility for treatment. This leaves approximately 15.7 million individuals who have yet to undergo this crucial process.

From February 28, 2025, SHA will begin using data from multiple government agencies—including the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), Hustler Fund, Ministry of Lands, and the Registrar of Companies—to ensure that self-employed Kenyans pay health premiums that accurately reflect their financial status.

The initiative aims to curb cases where individuals misrepresent their income to qualify for lower contributions under the Means Testing Tool, which assesses payments based on self-reported financial information. However, a major point of contention is the scientific means-testing system itself, which calculates individual contributions at 2.75% of a person’s income. The process requires individuals to answer financial questions, after which the system determines their required payment.

While salaried employees can more easily determine their contributions, informal sector workers—who make up a significant portion of the uninsured population—remain hesitant. Many fear being overcharged and struggle to navigate the process, particularly since incorrect responses could lead to unexpectedly high premiums.

Private hospitals bow out

Meanwhile, the Rural & Urban Private Hospitals Association of Kenya (RUPHA) has announced that its member hospitals will stop treating teachers, police officers, and SHA patients from Monday due to unpaid government bills and persistent system failures.

Speaking on Thursday, RUPHA Chairperson Dr Brian Lishenga expressed frustration over the ongoing challenges within SHA, warning that they are putting patients’ lives at risk and threatening the sustainability of health facilities.

"We have unpaid debts dating back to 2017, hospitals are defaulting on bank loans, essential medicines are running out, and many consultants haven’t been paid for years," he said.

He further noted that only 54% of hospitals have received payments from SHA, while 89% have reported portal failures, and 83% are struggling to verify patient eligibility due to system glitches.

RUPHA Deputy Chairperson Joseph Kariuki confirmed that hospitals will also stop offering services under Medical Administrators Kenya Limited (MAKL), the insurance provider for teachers and police officers.

"Starting Monday, we will no longer provide medical services to police officers and teachers under government insurance. There will be no services for teachers, police, or SHA patients until the government meets our demands," he stated.

The ongoing crisis underscores the urgent need for the government to address the system’s failures, as millions of Kenyans face uncertainty over their healthcare access.

The WHO Regional Office for Africa has raised concerns about the heavy reliance on out-of-pocket payments to fund healthcare across the continent. This financial burden continues to push millions of people into hardship, making healthcare increasingly inaccessible, especially for the most vulnerable populations.

Top Stories Today